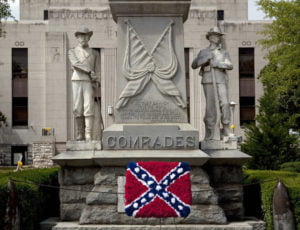

I am interested in the question of whether the relevant government officials and members of the public who together can remove the Confederate monuments, are morally obligated to (of their own volition) remove them. I am going to argue that they have a moral obligation to remove most, if not all, public Confederate monuments because of the unavoidable harm they inflict on undeserving persons.

- If the existence of a monument M unavoidably harms an undeserving group, then there is strong moral reason to end the existence of M.

- Public Confederate monuments unavoidably harm at least those who suffer as a result of (I) knowing the racist motivation behind the existence of most Confederate monuments or as a result of (II) having the horrors of the Civil War and the United States’ racist history made salient by public Confederate monuments.

- Therefore, there is strong moral reason to remove public Confederate monuments.

- If there is strong moral reason to remove public Confederate monuments, then absent stronger countervailing reasons to preserve them, people are morally obligated to (of their own volition) remove public Confederate monuments.

- There are no countervailing reasons to preserve public Confederate monuments that are stronger than the moral reasons to remove them. .

- Therefore, people are morally obligated to (of their own volition) remove public Confederate monuments.

I take (1) to be obviously true. It can be derived from the moral axiom that if x unavoidably harms morally considerable beings who don’t deserve to be harmed, then there is strong moral reason to prevent x (assuming, of course, that x is preventable).

At least the first disjunct of (2) is uncontroversial. People have been opposed to Confederate monuments as long as they’ve existed. The motivations behind the creation of Confederate monuments were transparent to those alive at the time of their creation. Knowledge of this history factors into manner in which people suffer as a result of seeing and knowing that the Confederate monuments are still standing. The second disjunct should be uncontroversial, though it appears to be overlooked in the debate. Consider someone unaware of the racist motivations for creating (most) Confederate monuments and who has the typical cursory knowledge of the Civil War. Suppose, hypothetically, that the Confederate monument they happen to see was created for entirely innocuous reasons. Does this Confederate monument still unavoidably harm them? Yes; at least, it will for some. This is because seeing the monument can non-voluntarily make salient America’s racist past and the horrors of one of the darkest periods in American history. Having these facts made salient can clearly cause one to suffer even if we grant that the monument itself is not racist and was not created for racist reasons.

Premise (4) should also be uncontroversial and can just be derived from a moral axiom which holds that if you have strong moral reason to x, then absent stronger reason to not x, you’re morally obligated to x. This only leaves (5), which is perhaps the most contentious premise of my argument. I’ll now consider what I take to be the best, or most common, objections and provide short responses to them.

Objection: Confederate monuments are works of art that have a great deal of aesthetic and historical value.

Responses:

- I deny that anything can possess aesthetic or historical value that has normative significance independently of its effects on well-being.

- If there is such value, it is not as important as preventing this undeserved harm suffered by oppressed groups.

- I deny that removing these monuments need result in the loss of any historical or aesthetic value.

a. There is not much aesthetic or historical value in the mass produced Confederate monuments created for racist reasons.

b. It’s possible to remove the Confederate monuments without the loss of any historic or aesthetic value (e.g. by placing them in a museum in the appropriate context).

Objection: Removing Confederate statues erases history.

Responses:

- I am extremely skeptical that Confederate statues themselves impart much in the way of historical knowledge or lend insight into what it was like to exist during the Civil War.

- Even granting (for the sake of argument) that there would be a non-trivial loss of historical knowledge if the monuments are removed, it doesn’t follow that there need be a net decrease in historical knowledge.

- Even if removing the monuments led to some unavoidable loss of historical knowledge, preventing that loss of value is just less important than preventing the amount of suffering Confederate monuments cause undeserving individuals to experience.

Objection: we can continue to preserve Confederate monuments solely to honor of the noble accomplishments of the people they valorize.

Responses:

- This is unlikely to be what would actually happen.

- Few would think it morally permissible to create a statue of Bill Cosby to honor him for his contribution to comedy even under the assumption that people would only be honoring Cosby for his honorable accomplishments. A good explanation for why this is wrong is because it’s simply more important to prevent the pain that a Cosby statue would cause survivors of sexual abuse than it is to benefit people desiring to honor Cosby. Ditto for Confederate monuments.

Objection: If we have to remove Confederate statues because they honor people who acted in ways that were gravely morally wrong, then wouldn’t we get the absurd conclusion that we have to remove almost all statues?

Responses:

- There is a difference between people like Thomas Jefferson or Mahatma Ghandi and people like Robert E. Lee or Nathan Bedford Forrest. While all of them committed grave moral wrongs, only the former group also accomplished a great deal of good and were, with respect to some issues, morally prescient.

- Statues of people in the former camp do not cause the same amount of unavoidable harm as people in the latter camp. The amount of harm that statues cause provide a principled reason to treat these cases differently.

I should note that this is a significantly truncated version of an argument I make in a forthcoming paper on the topic. Here’s the link to the preprint of that paper in case anyone is interested.

https://philpapers.org/rec/TIMACF

I’m quite interested to hear what everyone thinks about this issue.

Hi Travis!

Interesting post. Thanks for helping me see so many of the relevant factors. I wonder if you can say something about the last response, especially part 2, in the light of a Native American point of view. You mention the amount of unavoidable harm caused being “less” but I’m not yet clear on why you think confederate statues cause more harm, or more importantly harm that passes the relevant threshold, but statues of various US presidents do not. For example consider this post and others on various US presidents who are much more “strongly” celebrated with monuments (eg on the mall in DC and on all the money we use).

https://newsmaven.io/indiancountrytoday/archive/thomas-jefferson-architect-of-indian-removal-policy-kV7p2W8yLUeb47XLS5kJmg/

What about this one:

While the public display of Confederate Statues causes some distress for many, it also arouses a determination in those people to challenge present injustices. Making salient the imperfections of human nature and bringing to attention the inevitable failings of society, those encountering the monuments are made vigilant of present abuses and become determined and organized to resist such abuses. The statues produce tougher and more vigilant communities.

Hi Travis! I taught your essay in my ethics course last year and it occasioned one of the best discussions and a lot of paper topics. I like your conclusion (these statues should come down) but I’m suspicious of the welfare, consequentialist argument. What would you say to this scenario: Shameful Nazi Descendants. A few generations after WWII, suppose most Germans just feel ashamed about the Nazi regime, don’t feel like they are implicated in those atrocities anymore, and are ashamed of it. They don’t want to be reminded of it. A poll is taken, and indeed, a majority of Germans would like to remove all monuments dedicated to memorializing the atrocities of the Nazi regime. (Something like this, although also involving outright falsification, is happening in Hungary, as far as I understand). Is Germany morally obligated to remove these monuments? I take it that the first clause of (1) is satisfied (they are descendants, not perpetrators), but maybe not the second, ie., there are NOT strong moral reasons. But why not? They are ashamed of this past; and they resent feeling constantly associated with it – is that not a strong moral reason? I don’t know, but my intuition about Ashamed Nazi Descendants is that they should not remove the statues.

Fabulous piece, Travis! I’m very sympathetic. Here’s a stab at another objection: who qualifies as an undeserving group? Is it just one that did not contribute to this harm, or is there a stronger substantive notion in the background?

To fill this out: many who are unhappy about removing confederate statues take *themselves* to be suffering (and, perhaps, deserving of special consideration), whether from geographic economic inequalities; lack of social and educational standing; the rise of various social studies departments; or unflattering views in popular media. For at least some of these people, their frustration or sense of being left behind is real. Do we need a substantive notion to show that they are not deserving?

I realize that this is not exactly an objection to the argument, since this sense of aggrievement is not really at issue in the article–it’s not clear that losing the monuments, say, would address their aggrievement and/or balance out the harms to other groups of keeping them up (I am agnostic about this point, which I take to be empirical). But if we take this frustration seriously, I believe that could undermine part of the motivation behind this argument.

Hi all,

Thanks for your very helpful comments so far! I have been thinking about them and outlined my responses. I am teaching until 4:30 today (eastern time). As soon as I finish teaching, I will write out my responses and post them ASAP.

I thank Professor Timmerman for offering us the opportunity to comment on his rather interesting and provocative argument for removing Confederate monuments from the public domain. I welcome and share his moral sensitivity; however, I have a substantive reservation about the scope of his argument. Granted that the argument is valid, I would like to explore whether the argument is sound. My sense is that his argument seems to prove too much. Let me focus on premise 1: “If the existence of a monument M unavoidably harms an undeserving group, then there is strong moral reason to end the existence of M.” Let us take the antecedent expression “the existence of monument M unavoidably harms an undeserving group” as a place holder. Now we can add innumerable examples of books, paintings, national symbols, religious symbols, political symbols ad infinitum, and simultaneously claim with Professor Timmerman that there is a strong moral reason to end their existence. If that were to be the case, then our cultural understanding will be significantly impoverished. But we also have a strong moral reason not to deliberately and significantly impoverished our cultural understanding. Hence, we do not have a strong moral reason to end the existence of the innumerable examples already-mentioned. Evidently, professor Timmerman could argue that he is only focusing on Confederate monuments. Yet it is not clear to me what could prevent us from extending the argument as I did above. Nevertheless, even if my reservation is well taken, one could argue, in the spirit of Professor Timmerman’s view, that given our important duty of nonmaleficence to avoid deliberately harming undeserving people, we might still have an obligation to remove some Confederate monuments, but not necessarily all of them.

Here is a thought: Imagine you live in a country like the US, [call it US*] except it has not a single confederate monument [either never had one or they all have been removed]. Everything else in US* is exactly as it is in US right now. According to you it seems life for “undeserving groups” in US* should be significantly better than in US because an “unavoidable harm” has been removed. What is your evidence that this actually would be the case for [the majority of] an “undeserving group”, say people of colour. Remember, members of “undeserving groups” in US* are exposed to the same police brutality, lack of quality education, explicit and implicit racism etc. etc. as members of the same group in US. It seems there is some reason to doubt that accepting your argument [and acting on it] will result in a better life for the majority of the members of the group.

A common reply to this challenge is “Well yeah we should do other things for “undeserving groups” and those other things may have a much much bigger positive impact on their life than removing monuments. BUT this does not mean we should not also remove monuments. We can do both”

The sad reality is that we DON’T do both. In fact for members of privileged groups there might be a temptation to price compare: what does it cost to remove a monument [or even all monuments] vs. what does it cost to provide good and affordable education, health care, housing and fair policing [just to mention a few] to all members of “undeserving groups”. I trust you can do the math. So in my humble opinion, when it comes to moral obligations we have an obligation to do first what will benefit most members of “undeserving groups”, preferable what will most benefit those who are least well off. You can of course list such projects by urgency but it seems that removing monuments is pretty far down on a list of moral obligations if you take the perspective of those who suffer most from existing inequalities.

Hi Brad,

Thanks for your comment! The first thing to say is that I am not certain how much harm any individual statue causes and it seems quite difficult to gauge from the empirical evidence available. I was making a guess based, in part, on the amount of media coverage Confederate monuments get and the amount of protests surrounding them that I could find. But there is at best a tenuous connection between this and facts about how harmful each Confederate monument is to people.

I did find survey information about what percentage of people supported various monuments, but that also does not tell us much about whether those monuments are harmful. Many people may oppose monuments who are not themselves harmed by either their continue existence or their removal. Likewise, some people may support them even if they are (to some degree) harmed by their existence or removal.

So, the scope of my argument hinges on a tricky empirical issue. It could very well be the case that many monuments of presidents are comparably harmful to Confederate monuments. If so, then absent some other relevant difference between them and Confederate monuments, I would grant that these monuments of presidents should be removed too.

I want to mention one important feature of the longer version of my argument. It applies to individual monuments on a case by case basis. So, monuments of Jefferson may be quite harmful in some places, but not others. That could mean that the relevant groups should remove some, but not all, monuments of Jefferson.

In the longer version of the paper, I discussed a campaign to remove a statue of Gandhi from the University of Ghana. It was recently removed as a result of the protests

https://www.cnn.com/2018/12/14/africa/gandhi-statue-ghana-intl/index.html

Now, what is important is that the facts that the Ghandi statue made salient at the University of Ghana concerned the racist writings of the younger Ghandi, writings where he used racial slurs to refer to black South Africans. Given these considerations, I think the university probably should have removed *that* statue of Gandhi. Is the same true of the statue of Gandhi in Union Square in NYC? I am not sure, but I don’t think so. The facts made salient when people see that statue may generally concern is non-violent struggle for Indian independence, his fight for civil rights in South Africa, his fight for the emancipation of women and public declarations of the equality of the sexes. So, there may be good reason to keep the Union Square statue of Gandhi up. Ditto for presidential monuments and, for that matter, any monument.

Hi Daniel,

Thanks for your question. I want to provide two related responses.

First, this is an empirical issue. Without some very strong evidence in favor of this claim (one that shows it holds generally, not merely in certain cases), I remain quite skeptical that it’s true.

Second, one reason Confederate monuments (including statues) are harmful is because they’re reverential in nature. It seems to me like they could be placed in a proper historical context in such a way that they’re no longer reverential (e.g. by being moved to a museum and/or accompanying them with a historical overview that doesn’t simply glorify them), yet still manage to remind people of past injustices and motivate people to combat such injustices.

Similarly, it seems to me that such harmful monuments could be removed and replaced with non-harmful statues, or historical sites, or educational resources, or a variety of things that serve the same purpose.

In short, I am skeptical that Confederate monuments really provide the good you suggest they do and, even if they did, I doubt that they’re uniquely positioned to do so.

Hi Michael, thanks for assigning my paper in your course! That’s really neat that it has already been taught in a class. I didn’t realize anyone had done that until today.

Also, thanks for your probing question. One issue with the Hungary example, as you mention, is that outright falsification is happening. This falsification may affect our moral judgments. I like your Shameful Nazi Descendants example. This example also allows us to stipulate that no outright falsification is happening and better ensure that our judgments in that case are tracking the specific moral factors we’re trying to isolate.

I actually grant that both clauses of (1) are satisfied. If there is reason to keep the statues up it must be because there is some countervailing reasons to preserve the statues in question that are stronger than the moral reasons to take them down. So, the analogue of premise (5) could be false.

To know whether there are such countervailing reasons, we’d have to fill in the details of the case more. Perhaps the continued existence of the statues in question would prevent history from repeating itself or perhaps they benefit the descendants of the atrocities or perhaps they result in some other good. If this is the case, then I say they should stay up. My argument could capture your intuition then. This does mean that I think it can be permissible to inflict harm on an undeserving group (e.g. non-culpable Nazi descendants) in order to bring about some greater good (e.g. preventing history from repeating itself). But that’s the right view, I take it.

Now, if preserving the statues in Shameful Nazi Descendants really doesn’t bring about such goods, then I think they should be taken down. That doesn’t seem counter intuitive to me though. Why should they stay up if, as it is imagined in this case, their continued existence harms an undeserving group and doesn’t result in some comparably better good (that couldn’t have been obtained in a less harmful or non-harmful way)?

Thanks Kian and great question! I don’t want to say that in order to be undeserving it must be the case that one that did not contribute to the harm. All I had in mind was people (or groups) who do not deserve to suffer the harm in question. But I don’t take a stance on what determines whether some individual (or group) deserves to be harmed in the sense at issue. I am myself agnostic on the question.

I realize this is not a particularly helpful answer to your question. But I wanted my argument to be neutral with respect to the question of which groups count as undeserving.

Still, perhaps I can say something more helpful. I consider this objection in the full paper. Setting aside the question of whether I group is undeserving of harm, I also want to give priority to people whose harms are avoidable by the person being harmed. I furthermore claim that many (not necessarily all) people who claim they would be harmed by having the Confederate monuments removed *wouldn’t* be harmed if they rid themselves of certain unjustified beliefs and contemptible attitudes. I think we can give priority to harms not predicated on unjustified beliefs or contemptible attitudes over those that are, even if both groups in question are equally undeserving. If I am right, then this means we can give priority to the harms suffered by the Confederate monument abolitionists over the preservationists.

Kian, in case you’re interested in my more detailed response, I’ve copied and pasted the relevant portion from my paper below.

If we have strong moral reason to remove Confederate monuments because of the harm that preserving them causes, don’t we also have strong moral reason to preserve the monuments because of the harm removing them would cause? After all, there is no shortage of preservationists who claim they would suffer if the monuments are removed. Why should the harm inflicted by the preservation of the monuments be considered weightier than the harm inflicted by the removal of the monuments? The short answer is it shouldn’t, at least not in cases where (i) the same amount of harm at stake and (ii) the harm is predicated on fitting attitudes and rational beliefs. However, neither of those conditions are met when it comes to removing Confederate monuments.

Consider (ii) first. Much, though certainly not all, of the harm from which preservationists would suffer if Confederate monuments were removed crucially depends on them holding certain irrational beliefs or contemptable attitudes. For instance, the white nationalists chanting “Blood and Soil” in Charlottesville might lament the Robert E. Lee statue being taken down because they would view that as a hindrance to their goal of preserving the “superior” Aryan race. In short, the suffering they might endure as a result of the Lee statue being removed is predicated upon their heinous racist attitudes, beliefs, and goals. Were they to rid themselves of their racism, they would no longer suffer so much from the removal of the Lee statue. Assuming these white nationalists have the rational capacity to rid themselves of their irrational beliefs and contemptable attitudes, any suffering they endure that depends on them holding such attitudes and beliefs matters less than the suffering endured by people whose suffering is predicated upon rational beliefs and fitting attitudes. The suffering that results from the preservation of Confederate monuments is predicated on rational beliefs and fitting attitudes for reasons I gave in section 2. To be clear, I’m only claiming that much (not all) suffering that would result from removing Confederate monuments is predicated on irrational beliefs and contemptable attitudes. Preventing the suffering predicated on rational beliefs and fitting attitudes, however, takes precedence over the suffering predicated on irrational beliefs and contemptable attitudes.

Now consider (i). I believe it’s quite likely that the suffering that would result from the continued existence of Confederate monuments would be greater than the suffering that would result from removing them. This is largely because of the issue of salience mentioned in section 2. The continued existence of Confederate monuments would continue to cause people to suffer because of certain facts that the monuments make salient. However, were the monuments removed, their being removed would not similarly make harmful facts salient. Perhaps seeing the space where the monuments once stood would make the fact that the monuments were removed salient to some people, and having that fact made salient might cause some preservationists to suffer. But it seems highly unlikely that this would occur with much frequency. Moreover, the extent to which it would happen presumably would diminish with each generation. After all, future people who grow up without having ever seen a Confederate monument wouldn’t suddenly think about the absence of Confederate monuments when they’re in the areas where the monuments once stood. On the other hand, the continued existence of Confederate monuments would continue to make salient the horrors of the Civil War and the United States’ racist history.

In sum, these considerations do not justify rejecting premise (5). While the removal of Confederate monuments would likely harm some preservationists, it would likely result in less harm than preserving the monuments would and much of the harm their removal would cause is less important than the harm their preservation would cause.

Hi Vicente,

Thanks for your helpful question! Let me start by noting that I think this is a good worry to have. In the paper I considered the objection that my argument would prove too much with respect to monuments, essentially prohibiting building any monuments. I think I can draw a principled distinction between the monuments that should be removed and those that shouldn’t. In case that interests anyone, I will paste that relevant portion at the end of this comment.

But you raise the even greater worry that my argument would prove too much by requiring us to eliminate all sorts of works of art and other important part of cultures. I will have to think about this question in more detail. Here are my initial thoughts, however. First, I suspect that these harm-based considerations apply to a smaller portion of cultural goods than (I think) you do. Second, even if I am wrong about this, preventing our cultural understanding from becoming significantly impoverished may be a good that justified allowing certain harmful books, religious symbols, paintings, and so on to be preserved. But, thirdly, I suspect that many of these goods can be preserved in non-harmful ways even if they’re harmful in their current state. For instance, removing Confederate monuments and placing them in museums in the proper historical context may preserve (indeed, enhance) our cultural understanding while simultaneously removing the harmful element of them. But, again, I will have to think about this more. There are many interesting applications of this sort of argument I make and I would have to think through them on a case by case basis. Thank you for raising this worry!

Okay, if I haven’t bored readers enough already, here’s the response that I give to the slippery slope argument in the paper. But it’s a narrow version that applies only to monuments, and not (as Vicente interestingly suggested) all aspects of culture.

One may object that my argument leads to an absurd conclusion and, as such, it is reasonable to infer that there is something wrong with my argument even if one cannot identify which premise(s) is false. The reductio ad absurdum runs as follows. “If we have to remove Confederate statues because they honor people who acted in ways that were gravely morally wrong, then wouldn’t we get the absurd conclusion that we have to remove almost all statues?” George Washington and Thomas Jefferson both owned slaves, yet few object to monuments of them. Mahatma Gandhi notoriously expressed racist attitudes toward black South Africans and was an unrepentant misogynist, yet few object to monuments of him. Almost every contemporary person who has been honored with a monument is someone who routinely consumed factory-farmed meat, a fact that future generations will almost certainly regard as morally monstrous. Yet no one raises this as an objection to honoring anyone with reverential monuments.

If we remove all statues of people who’ve committed grave moral wrongs, wouldn’t we have to remove almost all statues? The answer to this question is “Yes.” Is that absurd? Not necessarily. But, more importantly, my argument does not entail that we have to remove the statues of everyone who has committed grave moral wrongs for a few reasons. First, it’s worth noting that there is a potentially morally relevant difference between people like Thomas Jefferson or Mahatma Gandhi and people like Robert E. Lee or Nathan Bedford Forrest. While all of them committed grave moral wrongs, the former group also accomplished a great deal of good and were, with respect to some issues, morally prescient. The same cannot truthfully be said of the Confederate generals.

Second, statues of people in the former camp do not cause the same amount of unavoidable harm as people in the latter camp. The motivations behind the creation of Gandhi or Jefferson monuments were not racist. They were not erected to further the oppression of anyone. Moreover, the facts that such statues make salient are generally not harmful because they concern the good that such people have done. When most people think of Gandhi, for instance, they think of his non-violent struggle for Indian independence. They don’t think (or generally even know) about his racism or sexism, but they may know about his noble fight for civil rights in South Africa or his fight for the emancipation of women (and public declarations of the equality of the sexes). Since these monuments are harmful in the way, or to the degree, that Confederate monuments are, it is plausible that the moral reasons to preserve them currently outweigh the moral reason to remove them. Of course, times change and cultures continue to evolve. It’s quite conceivable that, in the future, a majority of people will oppose monuments of Washington, Jefferson, Gandhi, and the like because of their gravely morally wrong actions. Their moral shortcomings may even become the facts that are salient when people see such statues and such monuments may come to harm as many people as Confederate monuments currently do. If that time comes, and the harm-based moral reasons to remove these statues outweigh the moral reasons to keep them up, then I grant that people at that time would be morally obligated to remove them. This is not an absurd conclusion, though. On the contrary, it seems to be exactly what we should do in that situation.

Hi Christina,

Thanks for your question. I like it a lot because it concerns another debate I work on, viz. the actualism/possibilism/hybridism debate in ethics. But before I get to that, I should make a clarificatory point. I never claimed that removing Confederate monuments would make marginalized groups “significantly better” off nor did I claim that it would benefit the “majority” of such groups. On the contrary, in the full paper I suggest that it won’t make a difference to most people’s welfare either way. Most people think Confederate monuments should be left up and while Reuters notes that there is some difference across racial and political lines, it’s unclear how pronounced that difference really is at the end of the day. What matters is that it does harm many and removing the Confederate monuments is part of the best series of acts groups can perform.

I also agree that there are more pressing issues than removing Confederate monuments. Who would deny that? Moreover, I agree that if it’s only possible to take care of some of the other issues you list or remove Confederate monuments, then priority ought to be given to the other, more pressing, issues. But all of that is perfectly consistent with my argument.

This is, in part, why I restricted the scope of my claim to what the relevant group of people morally ought to do of their own volition. They ought to . Now, as you anticipated, I hold that groups of people ought to do other things as well, including addressing the issues you listed. Let’s refer to those actions collectively as . So I hold that groups of people ought to do since that is what would result in the best outcome. Given that the group ought to and given that ought distributes through conjunction (O(A & B) → O(A) & O(B)) it follows that the group also ought to .

In response you suggested that it’s not true that the relevant group ought to because they won’t if they . I am not sure if that is true in this case. But even if it is, I deny that this allows the relevant group to avoid incurring an obligation to . I don’t think people or groups can avoid incurring obligations to perform the best set of acts they can in virtue of their rotten dispositions. For instance, suppose that the best set of actions I can perform includes . I can’t get out of my obligation to by choosing to if I . Likewise, the relevant groups cannot avoid incurring obligations to by choosing to if they . I say more about this issue and defend my favored position (i.e. hybridism) in a few papers, including the following co-authored paper.

https://philpapers.org/rec/TIMMOA

All that being noted, I want to make another conciliatory point. I also think there are practical considerations to be taken into account. So if the relevant groups, no matter what they collectively intend to do now, won’t work to address more important issues if they first remove Confederate monuments, then I claim they *practically* ought to leave the monuments up. They *practically* ought to do this, not because it’s the right thing to do, but because it will result in *less wrongdoing* than any alternative action they can now perform. But, here’s the rub, it’s still morally wrong for them to leave the monuments up and violating this moral obligation may ground negative reactive attitudes.

Thus far I have just been talking about groups. What about individuals? On my view, it may be the case that individuals are not obligated to try and remove Confederate monuments. The most good that any ordinary individual can do may not involve removing Confederate monuments. But that will depend on the individual.

Finally, I’ll note that we may have reason to promote at the expense of . Both groups and individual agents, when assessing their obligations, should hold fixed facts about how others would act when such actions are outside of their control. So, if the relevant group is not going to no matter what we do, then we may be obligated to focus on getting the relevant group to (if we could succeed) because that’s the best *we* can do even if it’s not the best *they* can do.

In short, I agree with you about the relative importance of this issue compared to others, and I agree how such issues should be prioritized, and I am open to the possibility that individuals and groups will fail to fulfill other, more important, obligations if they first fulfill their obligation to remove Confederate monuments. Nevertheless, I still think it’s true that the relevant groups of people who together can remove public Confederate monuments are obligated to do so of their own volition and that’s all that my argument here aimed to establish.

Whoops! My last comment got messed up. Let me try again without using the symbols that (I think) messed everything up.

Hi Christina,

Thanks for your question. I like it a lot because it concerns another debate I work on, viz. the actualism/possibilism/hybridism debate in ethics. But before I get to that, I should make a clarificatory point. I never claimed that removing Confederate monuments would make marginalized groups “significantly better” off nor did I claim that it would benefit the “majority” of such groups. On the contrary, in the full paper I suggest that it won’t make a difference to most people’s welfare either way. Most people think Confederate monuments should be left up and while Reuters notes that there is some difference across racial and political lines, it’s unclear how pronounced that difference really is at the end of the day. What matters is that it does harm many and removing the Confederate monuments is part of the best series of acts groups can perform.

I also agree that there are more pressing issues than removing Confederate monuments. Who would deny that? Moreover, I agree that if it’s only possible to take care of some of the other issues you list or remove Confederate monuments, then priority ought to be given to the other, more pressing, issues. But all of that is perfectly consistent with my argument.

This is, in part, why I restricted the scope of my claim to what the relevant group of people morally ought to do of their own volition. They ought to (A: remove most, if not all, public Confederate monuments). Now, as you anticipated, I hold that groups of people ought to do other things as well, including addressing the issues you listed. Let’s refer to those actions collectively as (B). So I hold that groups of people ought to do (A & B) since that is what would result in the best outcome. Given that the group ought to (A & B) and given that ought distributes through conjunction (O(A & B) → O(A) & O(B)) it follows that the group also ought to (A).

In response you suggested that it’s not true that the relevant group ought to (A) because they won’t (B) if they (A). I am not sure if that is true in this case. But even if it is, I deny that this allows the relevant group to avoid incurring an obligation to (A). I don’t think people or groups can avoid incurring obligations to perform the best set of acts they can in virtue of their rotten dispositions. For instance, suppose that the best set of actions I can perform includes (preventing an innocent person from dying today and preventing two innocent people from dying tomorrow). I can’t get out of my obligation to (prevent an innocent person from dying today) by choosing to (save no one tomorrow) if I (prevent an innocent person from dying today). Likewise, the relevant groups cannot avoid incurring obligations to (remove Confederate monuments) by choosing to (refrain from successfully combating other more important problems) if they (remove Confederate monuments). I say more about this issue and defend my favored position (i.e. hybridism) in a few papers, including the following co-authored paper.

https://philpapers.org/rec/TIMMOA

All that being noted, I want to make another conciliatory point. I also think there are practical considerations to be taken into account. So if the relevant groups, no matter what they collectively intend to do now, won’t work to address more important issues if they first remove Confederate monuments, then I claim they *practically* ought to leave the monuments up. They *practically* ought to do this, not because it’s the right thing to do, but because it will result in *less wrongdoing* than any alternative action they can now perform. But, here’s the rub, it’s still morally wrong for them to leave the monuments up and violating this moral obligation may ground negative reactive.

Thus far I have just been talking about groups. What about individuals? On my view, it may be the case that most individuals are not obligated to try and remove Confederate monuments. The most good that any ordinary individual can do may not involve removing Confederate monuments. Finally, I’ll note that we may have reason to promote (B) at the expense of (A). Both groups and individual agents, when assessing their obligations, should hold fixed facts about how others would act when such actions are outside of their control. So, if the relevant group is not going to (A & B) no matter what we do, then we may be obligated to focus on getting the relevant group to (B) (if we could succeed) because that’s the best *we* can do even if it’s not the best *they* can do.

In short, I agree with you about the relative importance of this issue compared to others, and I agree how such issues should be prioritized, and I am open to the possibility that individuals and groups will fail to fulfill other, more important, obligations if they first fulfill their obligation to remove Confederate monuments. Nevertheless, I still think it’s true that the relevant groups of people who together can remove public Confederate monuments are obligated to do so of their own volition and that’s all that my argument here aimed to establish.

Hi Travis – sorry for the belated response, just want to say thanks for the reply – persuasive!

Thanks for this great post, Travis! Sorry to be joining the conversation so late (I tried to post this comment Thursday evening, but I think it didn’t go through, so I’m trying again now.) I have three points I’d like to make.

First, I have some thoughts about a relevant difference between Confederate monuments and the monuments in Michael’s “Shameful Nazi Descendants” case. I think it’s plausible that the harms created by Confederate monuments are of a fundamentally different sort than the harms created by Holocaust memorials in the Nazi descendant case. A really important difference between Confederate monuments and monuments to the victims of Nazi atrocities concerns who is being valorized or celebrated. In the latter case, the victims of wrong-doing are being honored and remembered. Doing this respects them and their descendants. But I don’t think it disrespects the Nazis who harmed them: it’s a pro-victim memorial, rather than an anti-Nazi-descendant memorial.

For Confederate monuments that are likely to have a harmful impact, it’s often the perpetrators of wrong-doing who are being celebrated: the monuments valorize those who fought to keep slavery in place, or who fought against the rights of black Americans during Jim Crow (and erected the monuments for that reason). This might show respect to Confederate soldiers or leaders, and perhaps to their descendants. But it also seriously disrespects those who were slaves or who were oppressed under Jim Crow, as well as their descendants. If this is right, then the two kinds of monuments involve fundamentally different kinds of harm: Nazi victim memorials involve painful awareness of past crimes, but Confederate monuments involve both painful awareness of past harms of serious harms of disrespect. This may be enough to merit different treatment in the two cases, regardless of the other harms involved.

Second, I have a paper that’s of relevance to this discussion, where I address the general claim (raised in one of the objections you discuss) that we can “preserve Confederate monuments solely to honor of the noble accomplishments of the people they valorize.” (If anyone is interested in reading the full paper, please email me for a draft – aliberman [at] smu [dot] edu. I also address a version of this question applied narrowly to sexist art here: https://blog.apaonline.org/2019/01/02/women-in-philosophy-when-is-it-ethical-to-consume-sexist-art/)

In a nutshell, I think that this sort of endorsement—that is, supporting a Confederate monument because of the noble accomplishments of those valorized, and not because of the connections to slavery and racism—is only permissible if it meets certain conditions. Confederate monuments fail to meet one of the most important conditions, which I call “separability”: their good features (a commitment to fighting for state’s rights) cannot be meaningfully separated from their negative features (the state’s right to own and oppression black people.)

In general, I understand A as being separable from B if A is part of the shared social meaning of B—that is, if most folks in a society routinely and strongly associate X with Y, such that the social significance of one cannot be fully understood without the other. In the US today, most people associate Confederate monuments with slavery and/or Jim Crow era racism. Whether two things are part of the same shared social meeting will vary from one place to another; this can also explain why it makes sense to remove a statue of Ghandi at the University of Ghana (where he is routinely associated with racist writings) and not in New York City (where Ghandi is primarily associated with non-violent resistance to oppression.) It also helps us see why Confederate imagery would be unproblematic in certain contexts, such as museums, where it has a different social meaning.

Finally, there’s a really nice real-life example of an alternate mode of monument preservation outside of Budapest in Hungary. Called “Memento Park” in English, it’s a collection of (mostly very giant) Communist propaganda statues that were removed from public places and put in a park on the far outskirts of the city. The historical significance of the monuments is preserved for visitors in an open-air museum, but they’re not in a place in which they’re given an aura of reverence, or where people who would be harmed by painful reminders of the Soviet occupation of Hungary. You can find information about it here: http://www.mementopark.hu/

Hi Alida,

Thanks for your very helpful comments! I’m sorry they didn’t go through the first time around. I wonder what happened. Anyway, I don’t have much to add to what you wrote.

With respect to your first point, I just want to register agreement. With response to your second, I really love that blog post and the paper you reference (which I assume is the one you presented at WiNE). I find that argument quite plausible and the framework you develop to think about the issues very helpful. With respect to your third point, that’s a fascinating real life example. Thanks for sharing it!

This is an area of ethics that is, I believe, surprisingly underdeveloped. I hope more ethicists start working on these issues in the near future.