and I welcome you to the discussion of Gerald (Jerry) Gaus‘s recent “Self-Organizing Moral Systems: Beyond Social Contract Theory” (also available here). To kick off the discussion, we have a précis from Jeppe von Platz and reply from Gaus. Please join us in the discussion!

Comment on Gaus’ “Self-organizing moral systems: Beyond social contract theory”

Jeppe von Platz

In The Order of Public Reason, Gaus introduced a “Kantian Coordination Game” (Gaus 2011, 393-409). In this game, the players are members of the public, the choice options are the rules of the morality that regulate their social life, and the outcomes are the possible combinations of choices listed as utilities. Since the players care both about living by their most preferred rule, and also that they live together with others in accordance with shared rules; they prefer coordinate to non-coordinate outcomes. To illustrate, think of a so-called Battle of the Sexes, where the choice options are rules (cf. Gaus 2011, 395; 2016, 224; 2018, 123, 126):

Column R1 R2 Row

R1 2, 1 0, 0 R2 0, 0 1, 2

Things get more interesting when we think of iterated, multiplayer Kantian Coordination Games, where many players keep playing until equilibrium. In The Order of Public Reason, Gaus shows that some such games tend to an equilibrium where all players coordinate on one of the two rules. This finding establishes the possibility that members of the public can converge on endorsing moral rules even if they disagree about what the moral rules should be, as long as they care enough about living together in accordance with shared moral rules (Gaus 2011, 400-3, 409-10). If such rules are from the optimal eligible set (cf. Gaus 2011, 321-3; 2016, 214-5), then every member of a public can freely endorse the social morality that public has converged on. In these possible scenarios, the members of the public live together in accordance with a social morality that satisfies the public justification requirement (Gaus 2011, 27, 46, 263-4, 400-3; 2016, 224-6; see also Gaus 1996), in spite of their deep, intractable disagreement about what the rules of social morality should be:

“[W]e can achieve a free moral order while disagreeing on the ideal moral order. […] From the perspective of impartial reason – the moral point of view – no rule in the optimal eligible set is better than any other, yet social processes characterized by the increasing returns of a shared morality can lead us to converge on one rule, which then becomes the uniquely publicly justified rule.” (Gaus 2011, 446)

In “Self-organizing moral systems: Beyond social contract theory”, Gaus returns to and elaborates on Kantian Coordination Games (though he does not use the name). He models a series of such games and argues that the results establish the value of a specific form of diversity and the misguidedness of standard political philosophy.

In the models, N players choose from two rules {R1, R2} to live by. They have a relative preference between these rules scored on a scale from 1-10, so that each player assigns each rule a “justice-score” of 1-10. Again, the players care for living with others in accordance with shared rules (i.e., they care for reconciliation itself). This care then serves as a weighting function (wn where 0 < wn < 1) on their justice-score for Ri, for n players choosing Ri. Some additional notation:

Justice-score for player A of Ri: uA(Ri)

Weighting function for player A when n other players choosing Ri: wA(n)(Ri)

Utility for player A of option Ri with n players choosing Ri: UA(Ri) = uA(Ri)*wA(n)(Ri)

Player A prefers Ri to Rj if UA(Ri)>UA(Rj),

and is indifferent between Ri and Rj IFF UA(Ri) = UA(Rj)

Assuming that the weighting function for a player (A) wA(n) includes both ends of the scale (0 and 1), it follows that for any two rules, {Ri, Rj} and any two justice-scores (uARi, uARj) there will be some n where UA(Ri) > UA(Rj). That is, for any player there is some n at which they prefer coordinating with the majority on their less preferred option to coordinating with the minority on their more preferred option.

Using this framework, Gaus runs the games with different distributions of justice-scores, combinations of types of weighting functions, varying numbers of players, and updating functions.

Model 1

In the basic simulation, N = 101, justice-scores for R1 and R2 are random, and the players are sorted randomly into four weighting types (2018, 128-9, 145-7):

Quasi-Kantian players: zero weight (wn= 0) for rules chosen by 10% or less of N, full weight (wn= 1) for rules chosen by 50% or more of N (with roughly linear increase in weight for the range of n between 10% and 50%).

Moderately conditional players: zero weight (wn= 0) for rules chosen by 30% or less of N, full weight (wn=1) for rules chosen by 80% or more of N (with roughly linear increase in weight for the range of n between 30% and 80%).

Linear players: x% weight to Ri with x% of N choosing Ri.

Highly conditional players: zero weight (wn=0) for rules chosen by 33% or less of N, weight (wn=1) for rules chosen by 90% or more of N (with roughly convex increase in weight for the range of n between 33% and 90%).

In the first round, players choose the option with the highest justice score (and R1 if the justice scores are tied). In following rounds, the players update their choice in simple inductive fashion, changing their choice IFF they would have received higher utility playing the alternative in the previous round (2018, 131-3). Gaus reports on a game where the initial distribution was that 51 players chose R2 and 50 players R1. After five periods of play the population had converged on R2 (i.e., all players played R2).

Gaus also reports that he found convergence in games that included only three of the weighting-types, though convergence was delayed by one or two periods with the elimination of quasi-Kantians and highly conditional cooperators.

Model 2

In Model 2, Gaus investigates what happens with a population polarized between R1 and R2. To do so, he divides the population of 101 players into hi-lo groups, the first randomly scoring 6-10 for R1 and 1-4 for R2 and the other group randomly scoring 6-10 for R2 and 1-4 for R1.

With randomized weighting types, a closely split population of 52 players with high scores for R1 and 49 with high scores for R2, the population did not converge but found a divided equilibrium. A less evenly split population with 56 players with high R1 scores and 45 players with high R2 scores converged on R1 in four periods of play. Gaus again ran the model with combinations of three weighting types and found that delayed convergence by one to four periods, with the highest delay from leaving out highly conditional players.

Gaus finds it significant that the shortest route to convergence is the game with all four weighting types: “as we add diversity of weighting types, polarization can be more easily overcome than in many more homogenous populations […] Here, we see the possibility that one type of diversity can counteract the centrifugal tendencies of another.” (2018, 135)

Model 3

The first two models took the whole population as the reference network for each of the players, but real persons tend to define their values (and choose which rules to live by) in light of the choices and their normative and empirical expectations about a limited segment of the population (for definitions of social expectations and reference networks, see Bicchieri 2016). So, in the third model Gaus segments the population into different reference networks (2018, 135-8). The population increases to 150 distributed across five groups of different polarity as follows (2018, 136):

Group A, 50 players: random justice-scores.

Group B1, 25 players: 20 players high justice score R1, the remaining 5 high for R2

Group B2, 25 players: 20 players high justice score R1, the remaining 5 high for R2

Group C1, 25 players: 20 players high justice score R2, the remaining 5 high for R1

Group C2, 25 players: 20 players high justice score R2, the remaining 5 high for R1

Splitting the otherwise identical B1/B2 and C1/C2 into separate groups allows them to be part of different reference networks, as follows (2018, 136):

Group Reference network B2 B1, B2 B1 B1, B2, A A A, B1, C1 C1 C1, C2, A C2 C1, C2

The reference groups are the basis for player updates, so that a player updates her choice in light of the distribution of choices in her reference network. Also, Gaus has the players update sequentially, so that in each period of play, group A updates and acts first, then B1, B2, C1, and finally C2 (2018, 137).

This is not an innocent change, and I am not clear why Gaus made it. Gaus writes that this change was made “because we have different groups that employ different updating calculations” (2018, 127), but that feature of the game by itself does not seem to warrant the change (players could update as a function of the choices in previous rounds as in the other models). And the change might be nocent (and Gaus agrees [2018, 137]), since sequential move coordination games have few of the interesting properties of simultaneous move coordination games. As the Battle of the Sexes illustrates, a sequential move coordination game may have little interest except to illustrate first mover advantage. The initial distribution of justice-scores and weighting types in A thus disproportionately influences the game. This would be less of an issue if Gaus ran a high number of simulations and reported the result as a probability distribution, but weakens the general implications of a single run of the game.

In any case, with this updating rule, distribution of types, and reference networks, the model obtained convergence on R1 in ten periods, with the C2 group converging last.

Gaus reports on a few variations of this simulation and notes two more results. First, in simulations with homogenous populations of linear agents or quasi-Kantians, none of the five subgroups (A, B1, B2, C1, C2) achieved sub-group convergence. Second, in another simulation all 20 of the high justice-score for R2 from C2 were joined by four from C1 and these together formed an “R2 network” (2018, 138), so this model ended in an equilibrium with a split population of 126 choosing R1 and 24 choosing R2. The result was caused by quasi-Kantians in C1 being immune to the pull from switches in the random group (A), which kept those favoring R2 in C2 from switching. These two results are interesting, Gaus ventures, since they both suggest that weighting diversity is an advantage.

Minor worries

The results of the models are, of course, functions of the numbers that factor into player utilities, and it would have been good to see a justification for the choices of numbers.

First, why do all the weighting types include both minimal (0) and full weight (1) at some n? If the models included reluctant cooperators (i.e. types that never give full weight to a rule they disagree with or zero weight to a rule they prefer), then convergence would be less likely.

Next, if the justice-utility scale started at 0, then convergence would not be forthcoming for those that value either R1 or R2 at 0. Gaus might reply that the rules are all from the “socially eligible set” (Gaus 2011, 322), which means that all players rank any rule higher than no rule or “blameless liberty” (e.g. Gaus 1990, 281-3; 2011, 316-7, 322, 341; 2016, 187-90, 211-4). That reply introduces the assumption that the argument is limited to rules from the socially eligible set.

Finally, it is a bit odd that Gaus’ models treat justice-scores and weights as independent variables; surely, we can expect correlation between the degree to which a person believes a rule is preferable and the degree to which they are willing to discount it when others don’t act on it?

Having flagged these minor worries, I’ll turn to my one complaint.

My one complaint (in two parts)

My one complaint is that Gaus frames his argument as being about the value of diversity and the misguidedness of traditional moral philosophy, especially Rawlsian contractualism. This framing is vintage Gaus, but odd; for these claims are weakly supported by his arguments, and the framing hides what I think is the wild and exciting idea illustrated in the essay.

Part One: A wild and exciting idea!

The idea starts with the Humean view that morality answers our need for rules by which we can live together, and by which we can make, navigate, negotiate, judge, and settle claims on each other. We disagree about what these rules should be, but the need for such rules is indisputable.

There are many candidate rules. We can sort these into three sets: all rules, the socially eligible set, and the optimal eligible set. The socially eligible set is a subset of the total set of rules, and the optimal set is a subset of the socially eligible set.

But which of the eligible rules should we rely on for justification of our actions or to negotiate conflicting claims? Here Gaus makes an original suggestion: any and all of the eligible rules are valid sources of moral justification and claims, if the members of society endorse them as such. Moreover, the members of society might come to endorse a set of rules simply because they care enough for living together in accordance with shared rules. In other words, it is possible that all members endorse a rule Ri, because for any person, and any rule Rx other than Ri: U(Ri) > U(Rx), even if Ri is not the most preferred rule of any member of society, for U(Ri) is a function both of the justice-utility and the weighting function, which, in turn is variable with the number of persons that act on Ri.

Morality is thus indeterminate; the members of society could converge on any of the rules of the eligible set, and if they do that rule is valid for that society. Startlingly, there can be multiple and contradictory valid moralities: a society could converge on any of the members of the eligible set, it might change over time from one convergence point to a contradictory one, and different societies might be governed by different moralities, each of which would be valid for them.

Gaus can thus apply the idea of (impure) procedural justice to morality itself! The morality we should live by is the one that we have converged upon, if we have converged on a morality that is in the eligible set (this condition is the impurity). Two worries here are that we might not converge on any set of rules or that we might converge on a non-eligible morality. So, moral philosophy should seek the conditions of convergence and the limits of eligibility.

The main parts of this idea were developed in The Order of Public Reason, but the models in “Self-organizing systems” illustrate and add depth to it. “Self-organizing systems” provides a deeper sense of the complexity and indeterminacy of social morality. This complexity and indeterminacy are illustrated by the multiple equilibria that might obtain from playing any of even the simple games modelled in “Self-organizing systems”; not so much by the results that Gaus reports, but by the fact that the equilibria these games result in can vary with minute variations in the input. The equilibria reached in such complex games are functions of positive feedbacks, cascades, band-wagoning, self-reinforcing mechanisms, path-dependency, and like mechanisms (cf. Arthur, 1994). Will a society converge on some rule (R1 or R2 or…) or reach a divided equilibrium? It depends on a number of factors – justice-scores, weighting-functions, the distribution of justice-scores and weighting functions at t0, updating functions, reference networks, and so on – where even minute variations in the factors can lead to different equilibria, convergent or divided.

Morality is like that! A valid moral code is partially a random affair – the result of an ongoing (complex, reiterated, and continually disturbed) game. And yet, positive morality is the valid source of moral claims, if and because the members of society have converged on it (i.e., if they have converged on a set of eligible rules).

Gaus could have done more to illustrate the complexity of social morality. In particular, and I say this as a friendly suggestion, Gaus leaves it unclear how many simulations he ran with each model and the results he reports are from one or a few simulations where the players converged or failed to converge in some run of the model. These specific results are interesting and serve to prove possibilities, but it would, I think, be more interesting and illustrative to reveal more of the general structure and solutions of these games. The games modeled by Gaus are interesting in part because they have multiple equilibria; for each of the games, the general outcome (the solution) would be a probability distribution over the set of possible equilibria that could be computed directly or approximated by running enough simulations and plotting the outcomes. The illustrative power of these models would’ve been strengthened by revealing the general results.

Part Two: Inferential shortcomings

Gaus suggests two conclusions (139-41):

I. Diversity (of weighting types) is good, since it increases the likelihood of reconciliation.

II. Standard political philosophy is mistaken. This mistake is compounded in the Rawlsian contractualist search for consensus.

Ad. I. Yay, diversity!?

Gaus argues that it is desirable to have a diversity of types of weighting functions in a population. The argument is that convergence is more likely (and happens faster) in games with all four weighting types than in games that leave out one of them, which also means that diversity of weighting types can help overcome polarity in the population.

The result that more diversity of weighting types sometimes aids convergence is clear, but what can we infer from that about the value of diversity as such?

Alas, not much. The argument establishes the desirability of additional weighting types of particular sorts in some situations, but sometimes convergence would come easier with less weighting type diversity. To be simple about it, the condition most hospitable to convergence is if all members are of a single weighting type that shifts weight from 0 to 1 as soon as more than 50% of the population favors one of two rules (for then any majority in round one secures full convergence in round two). So, Gaus needs to say more to establish that weighting type diversity is a good thing.

Also, Gaus’ argument seems to go against the value of perspective diversity (on perspectives, see Gaus 2016 and Muldoon 2016). In “Self-organizing systems”, perspective diversity is treated as a problem, since it makes convergence harder to obtain. That’s why Gaus emphasizes the “possibility that one type of diversity [weighting] can counteract the centrifugal tendencies of another [perspective].” (2018, 135) Here I see a tension in Gaus’ position. On one hand, perspective diversity is attractive in its own right and also epistemically, since it allows us to better search for moral ideals (Gaus 2016, chapter 3; 2018b). Yet, on the other hand, perspective diversity is undesirable, since it makes it harder for us to live together in accordance with shared rules. The tension is brought out, I think, by the moral psychology of convergence. Say that we converged on a social morality, developed the attendant moral psychology, taught it to our children, and so on. The problem of finding stable, shared, valid rules is solved, but perspective diversity is lost. That would not, I think (and I expect Gaus agrees), be a desirable situation. But then convergence might not be desirable after all, in which case the sort of weighting diversity that is conducive to convergence is undesirable.

Ad. II. Convergence ⊕ consensus!?

I have thus far bypassed the first three sections of the paper, which place Gaus’ results in the context of his larger engagement with the aims and methods of standard moral philosophy. Gaus frames his project in terms of the misguidedness of moral philosophy and the social contract tradition as traditionally conceived. Gaus claims that moral philosophy and the social contract tradition fail to see the significance of moral disagreement; our object should be neither truth nor the content of consensus, but the conditions of convergence.

Gaus initially notes the difference between two modes of moral reasoning (Gaus 2011, 120-4):

i. Standard moral philosophy, which pursues an individualistic mode of thinking and seeks true judgments of the form “We ought to φ”.

ii. The social contract tradition, which pursues a reconciliation mode of thinking and seeks true judgments of the form “We believe we ought to φ”.

The social contract tradition registers that we seem to make no progress in the first-order project and therefore shifts to search for a consensus that we can use to navigate our first-order disagreements. Motivated by the aim to overcome moral disagreement, the social contract tradition endorses a “reconciliation requirement: Individuals must seek out some device of agreement that reconciles their differences so that they can share convictions about what justice demands we do.” (2018, 122) This branch of the social contract tradition, exemplified by Rawls, seeks to meet this reconciliation requirement by finding norms or principles that all agree to (2018, 124, 139-40). That search must fail, Gaus argues, for “at the end of the day, it is a theory of what the theorist believes that we all believe what we all ought to do […] and for the same reasons we disagree in our simple ‘I believe we ought’ judgments, we disagree in our ‘I believe we believe we ought’ judgments.” (2018, 125)

The range of deep and intractable disagreement includes religious and metaphysical matters, the meaning of life, theories of value, what principles of justice we should live by, and even the importance of living together in accordance with shared principles of justice. Faced with this range of disagreement, we should abandon the quest for consensus.

What we should seek, instead, are the conditions for free moral inquiry and convergence on shared rules (elsewhere Gaus argues that these conditions are best secure by a Hayekian liberal constitution, i.e., “The Open Society” [Gaus, 2011, Part Two; 2016, Chapter IV; 2018b]). When the conditions of free inquiry and convergence obtain, the morality that the members of society converge upon is valid, even if it could have been otherwise. In another recent essay, Gaus writes that this “new program for political philosophy […] switches focus from the moral convictions and plans of the philosopher to those of the agents who form the self-organizing and self-governing moral order. […] In place of conceptions and plans for justice the new program […] seeks to identify “devices” of public reason, to analyze how markets, democracy, polycentrism, liberty rules and jurisdictional rights provide the framework for diverse moral perspectives to form moral and political orders that not only accommodate, but improve, their disparate understandings of justice in an open society.” (2016b, 75)

However, nothing in “Self-organizing moral systems” (or Gaus’ other writings) implies that that we should abandon the old program in favor of the new; that traditional moral philosophy or Rawlsian constructivism are not worthwhile enterprises. To affirm a particular moral perspective is also to assert that it enjoys better argumentative support than alternative perspectives. Every person that has beliefs about the differential validity of moral rules claims that their beliefs have objective validity – the model may randomly assign justice-scores, but agents have reasons for their beliefs about morality. Traditional moral philosophy attempts to establish which beliefs we should have and to assess the relative merits of different beliefs, by assessing the pros and cons of various perspectives; and any agent that has normative beliefs engages in traditional moral philosophy. Surely, it is a worthwhile use of resources to have moral philosophers investigating beliefs, their inferential bases, commitments, and implications – without such investigation, where would agents turn for deep and critical thinking about what perspective, rule, value, or other normative belief they should affirm? The Gausian project takes existing beliefs as input, but we also want to discuss what existing beliefs should be. To advance the “new program of political philosophy” as alternative to the old, is like saying that social science should shift from first-order studies to a program of meta-analysis.

Rawlsian constructivism – and the social contract tradition – provides one avenue of moral inquiry, targeted in part to address the specific question of political legitimacy in a diverse society. The search for consensus might be futile, but it might not – and the search itself can bring about insights that could otherwise be missed. Gaus often emphasizes Rawls’s admission that the overlapping consensus is on a family of liberal conceptions of justice, not on justice as fairness alone (Rawls 2005, xlvii-l; Gaus, 2015, 126; 2016, 153, 157;). Yes, there can be reasonable disagreement even about which liberal conception we should rely on in the design of the basic structure. But didn’t the search for consensus yield a positive and worthwhile result – that there is a limited range of liberal constitutions that can satisfy the demands of democratic equality and a sketch of the minimal conditions any such constitution must satisfy? We might even say that Rawls’s search for consensus identified a limited eligible set of constitutions. Rawls could agree that the choice of any of these is equally good, so any of these could be the basis of a just and legitimate political society.

Traditional moral philosophy is not shown to be a mistaken exercise by Gaus’ argument, nor does Gaus establish the futility of Rawlsian contractualism. Gaus shows that there is another worthwhile enterprise in moral philosophy – the search for conditions of free inquiry and convergence – but the value of diversity extends to modes of inquiry.

Conclusion

Here are four different questions of political philosophy:

- Who should get what – and why?

- What are the true principles of justice?

- What principles of justice can we all agree to, as free and equal persons?

- What are the conditions under which we can come to endorse (converge on) principles of justice, even though we disagree about what those principles these should be?

Gaus has done much to establish the importance of the fourth question, and provides a sophisticated answer to it. But he has not established that trying to answer the second and third questions is not worthwhile – even necessary – to find good answers to the first.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Ryan Muldoon for organizing this discussion and for comments on a draft of my part; to Chris Melenovsky for a helpful conversation; and to Jerry Gaus for wild and exciting ideas.

References

Arthur, Brian W., 1994. Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economic. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Bicchieri, Christina, 2016. Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure, and Change Social Norms. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Gaus, Gerald, 2018. “Self-organizing moral systems: Beyond social contract theory”. Politics, Philosophy & Economics. Vol. 17(2), pp. 119-147.

—- 2018b. “Political Philosophy as the Study of Complex Normative Systems”. Cosmos+Taxis: Studies in Emergent Order and Organization. Vol. 5(2).

—– 2015. “Public Reason Liberalism”. In S. Wall (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Liberalism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

—– 2016. Tyranny of the Ideal. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

—– 2011. The Order of Public Reason. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

—– 1996. Justificatory Liberalism: An Essay on Epistemology and Political Theory. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

—- 1990. Value and Justification: The Foundations of Liberal Theory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Muldoon, Ryan, 2016. Social Contract Theory for a Diverse World: Beyond Tolerance. London, UK: Routledge.

Rawls, John, 2005. Political Liberalism (Expanded Edition). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

REPLY BY JERRY GAUS

Thanks to Ryan Muldoon and Chad Van Schoelandt for focusing on my paper, and especially to Jeppe von Platz for his comments. I say this not in the way I sometimes do ¾ between gritted teeth controlling exasperation at basic misinterpretations ¾ but genuinely. They are great comments. If I had Jeppe’s comments before I finished the paper I certainly would have done the simulations differently. But that is the advantage of trying to be clear and more formal in what one is doing, for others can pick up on one’s idea and improve upon it.

Let me just make four general comments, which I think will advance the discussion (if there is any!).

1. The aim of the paper was to advance a proof of concept: that under some conditions increased diversity can make agreement easier. The original version of the paper simply sketched out the logic of the model, and that seemed the important point: to see the logic of how, under some parameters, increasing diversity could lead from deadlock to convergence. That still strikes me as a cool idea. Having sketched out the model, I thought it would be useful to provide some simulations to better show how the logic would work. They turned out a bit more interesting than I expected, but they are still baby ¾ perhaps neonate ¾ I hope that others will do a better job, and estimate something like basins of attraction for agreement and divergence for different populations. The complexities that Jeppe notes are all critical to such further inquiry.

I do think the proof of concept, though, is in many ways the crucial thing. As I modelled it, the problem is this. When we use our reflective capacity for moral thinking we disagree. As social philosophers we look around us, and we see our societies riven by one moral dispute after another. These are not disputes about “the good,” where if we dig deeper we get to a shared conception of “the right” ¾ these are disputes about the right itself. How can we handle them? Thus one of my wild ideas. What if, sometimes, disagreeing about what is right helps induce convergence on our shared rules of right? I thought that this conjecture is so deeply counterintuitive that a proof of concept was necessary. Hence this paper.

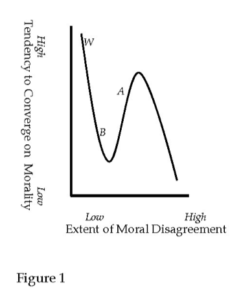

2. I certainly don’t, however, think that the tendency to converge on a moral rule is a positive increasing function of disagreement about morality. That would be mad, even for me. My conjecture would be that the relation might be something like Figure 1:

If a relation in that neighborhood was discovered, that would indeed be important for thinking about a shared morality. If we were at point A we need not seek to “normalize” away diversity: the processes I pointed to in the paper might produce considerable convergence. Not, of course, agreement of the sort we could obtain if we all endorsed the same conception of justice as in W, a well-ordered society, but that is an illusion anyway. The paper, as I have said, only advanced a proof of concept that point A can be more about hospitable to convergence than point B.

3. Supposing that moral disagreement is part and parcel of perspectival diversity, Figure 1 implies that we can only have so much perspectival diversity in a society that shares a common morality. I think we can push a long way towards drawing on diversity in a shared moral system, but there are limits. Thus, I embrace what Jeppe sees as an unpalatable conclusion: a shared morality limits perspectival diversity. Moreover, dynamically, he is no doubt correct that as we converge “on a social morality” and develop “the attendant moral psychology” and teach this morality to our children, the “problem of finding stable, shared, valid rules is solved, but [some] perspective diversity is lost.” It is important that to share a rule is not to adopt the same perspective, for different perspectives may have very different views of a rule and how well it accords with the perspective’s view of optimal morality. Still, there are limits on how diverse a range of perspectives can embrace a shared rule (think of the Nazi who regularly comes up in Q&A for a public reason paper in a philosophy seminar). The aim of the theorist of the open society is to see how much diversity ¾ or, more correctly, what patterns of diversity ¾ are consistent with a shared moral life that allows us to benefit from each other’s diversity. As Scott Page (2011) notes, diversity, while it often improves a system, at some point can become dysfunctional: the problem is how to draw on it and encourage it, while maintaining system functionality. How far right on the x axis can a society with a functional morality proceed?

4. My favorite phrase of Jeppe’s — it really did make me smile — is “vintage Gaus, but odd.” (I thank him for the “but”). His main complaint is that “Gaus frames his argument as being about the value of diversity and the misguidedness of traditional moral philosophy, especially Rawlsian contractualism,” and he find this unsupported. Oddly (in a different way), I intended this paper as accommodating the claims of traditional moral thinking, which I associated with the “I believe we ought” approach. This is a genuine and inevitable way in which people approach moral thinking, and I associate it with moral and much political philosophy. The paper accepts this, and does not target it. But Jeppe is quite correct that I do not see much value added to political philosophy by tweaking yet another “theory of justice.” Surely decreasing returns must be pretty far along on this production curve. Nevertheless I realize that philosophers immensely enjoy producing and criticizing such “theories,” and I do not wish to begrudge people this fun. And (with apologies to T.B. Macaulay) “it certainly hurts the health less than hard drinking . . . is not much more laughable than phrenology, and is immeasurably more humane than cock-fighting.”

The point of the paper — and much of my work — is that this first-order model of personal inquiry into what “I think we all ought to do” confronts us with the real problematic of current social philosophy: these enquiries purport to tell us all what to do, but we deeply disagree on what these results are. Thus the crucial project introduced most clearly by Rawls: a second-order analysis — what at one point (1975) Rawls called “moral theory” — to discover what sort of functional framework can arise under the moral diversity of modernity. The diverse outputs of the first-order (“I believe we ought”) inquiry are in the inputs to this second-order reconciliation project. The focus of my critical arguments is on contractualism understood as a second-order inquiry. At least since the mid-1970s Rawlsian contractualism presented itself as such a second-order “moral theory” (Gaus and Van Schoelandt, 2017), and I do indeed believe that it fails in these terms. It fails because it seeks the second-order theory via consensus. (Bargain-based second-order theories, I argue in the paper, fail for a different reason.) In terms of Figure 1, Rawls aimed at state W, where we agree about justice. That is fine for a first-order theory (why not “create” a well-ordered utopia?), but it undermines contractualism’s claim to be an effective way of reconciling conflicting first-order judgments (aka “theories of justice”). Rawls came to recognize this, and point W essentially vanishes in his final analyses. Still, his commitment to consensus makes rightward movement on the x axis difficult: point B probably already is a move too far.

Enough from me. Again, my definitely non-gritted thanks to Jeppe for thinking about my paper — and other of my writings — and saying such smart things.

Jerry Gaus

References

Gaus, Gerald and Chad Van Schoelandt (2017). “Consensus on What? Convergence for What? Four Models of Political Liberalism.” Ethics, vol. 128 (October): 145–172.

Page, Scott E. (2011) Diversity and Complexity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rawls, John (1975). “The Independence of Moral Theory.” In John Rawls: Collected Papers, edited by Samuel Freeman. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999: 286-302.

Thanks to Chad and Ryan for organizing this discussion, to Jerry for the interesting paper, and to Jeppe for his thought-provoking comments.

One crucial assumption of both the older Kantian coordination game and its newer agent-based cousin is that people are motivated entirely by their convictions about justice or morality. This is a perfectly fine assumption given that the purpose of the model is, as Jerry puts it, to provide a proof of concept. But if we are interested more generally in how morally diverse individuals coordinate, then I wonder how allowing in other sorts of motivations—say, those pertaining to one’s material self-interest—would change the story. To model this, we would need to add another argument to individuals’ utility functions: in addition to a concern with intrinsic justice and reconciliation, people care about how much they personally benefit from rules. Interestingly, self-interested benefits may be similarly subject to increasing returns—most of the time, I benefit more from complying with a rule that more people are complying with, given the possibility of formal and informal sanctions, greater cooperative benefits, etc. And perhaps we would want to impose an imperfect correlation between rules that one morally prefers and those that further one’s self-interest, to capture the idea that that people’s moral reasoning is biased by self-interest. Nevertheless, a model taking into account self-interest may generate some different dynamics than the one that assumes perfectly moral agents, and these may be worth exploring.

For example, suppose that while both moral and self-interested motivation involve increasing returns, the reference group for each differs: I gain more moral utility from rules as more people who (say) share my religion comply with them, whereas I gain more self-interested utility from rules as more people who are (say) in a position to reward or punish me comply with them, where these groups only partially overlap. In that case, I conjecture that we would sometimes find that allowing self-interest into the model actually promotes coordination, because it allows populations to overcome polarization by effectively creating overlaps between groups of agents that would remain entirely separate if populated by purely moral agents. The risk, though, is that self-interest may also make us more likely to coordinate on rules that are socially suboptimal or ineligible from the perspective of people’s moral utility alone. In other words, my hypothesis is that self-interest may make coordination easier, but also make coordination on morally unacceptable rules more likely, than the current model suggests. But this is all offered in the spirit of exploration (and of getting the conversation going), not in the spirit of criticism.

Thanks for providing a forum to discuss an interesting paper (and to Jeppe for helping get discussion going). I’ve only got time to post a short comment at the moment, but there was dynamic in the model that struck me as initially surprising as well as a potential dynamic that was not explored but worth looking at in future work.

The surprising result: removing highly conditional cooperators often has a huge impact on the speed with which populations converge. What makes this surprising is that this group is defined in such a way that they seem like they would be likely to be relative “latecomers” to the convergence dynamic. After all, they’re only motivated to go along with what they perceive to be a suboptimal norm when the vast majority of other agents are already doing so. Of course, it’s not surprising that groups of just highly conditional cooperators get convergence dynamics going quickly. But it’s surprising that they have such a big impact on heterogeneous groups.

Worth investigating further: plausibly one’s taste for reconciliation will be correlated with the first order moral commitments one has. This suggests the potential for a different kind of polarization dynamic than the one discussed in the paper. What if agents with hi-lo preferences for R1 also tend to be quasi Kantians, while agents with hi-lo preferences for R2 tend to be super Humean highly conditional cooperators? One conjecture: in environments dominated by agents of those types it might be possible to generate scenarios where convergence cascades lead rules initially in the minority to take over a population. That would be a cool result!

Finally, one last thought on different types of diversity. Another issue that crops up here, which Jerry has thought about in other contexts, is how perspectival diversity interacts with these kinds of dynamics. One particularly important question here is what happens when agents disagree about which rule is operative in a given environment/population (because they have different views of how that rule manifests itself in the world). That obviously greatly complicates the convergence dynamics studied here. And it makes sense to ignore it for the purposes of the proof of concept work set out here. But if we’re going to think seriously about leveraging diversity in moral orders, that kind of question will be important.

Thanks to Jerry and Jeppe for their illuminating work and to Chad and Jeff Carroll for ideas about my post. Thanks also to Chad and Ryan for making this opportunity happen for us.

Here’s one more line of inquiry we might pursue. Jeppe’s concluding schema lists four questions, and answers to questions 2-3 (about the true principles of justice and those to which free and equal persons could agree) seem to be required for an answer to question 1 (who should get what and why). But might we interpret Jerry’s work on question 4, about the conditions of valid convergence given deep epistemic disagreement, as implying that we must first answer 4 if we are satisfactorily to answer 1-3? It is notable here that Jerry’s discussion of 4 is at least not meant to supplant traditional theorizing about 2-3. Let us accordingly allow, arguendo, that questions about the conditions in which a political society can be expected validly to endorse principles of justice by a convergence mechanism ought, rationally, to be epistemically prior to questions concerning the truths of justice and what satisfaction of those truths (i.e., questions 1 and 2 in Jeppe’s schema) demands. What then? We might home in, I suggest, on two of many considerations as to whether a convergence view could generate rules that sufficiently account for perspectival diversity.

(1) In what ways if any must the relevant sort(s) of convergence view account for agents’ local knowledge, including knowledge generated and embodied by their life narratives? This is worth asking because how people see their lives unfolding seems obviously important for the kinds of rules they think are justified in the social spaces in which those lives play out. Relatedly, (2), it is psychologically plausible that many members of political societies who have such ‘local’ knowledge often do not know, or fully know, they do. Much of it might, for instance, be know-how, including with respect to how to treat others justly within and (as Dewey thought) through institutions. Further, there presumably are other members who have such knowledge and know they do, but do not know whether and how having this knowledge informs their dispositions to converge in ways that yield second-order justification.

All of this points to a large issue if, as we’ve allowed controversially, question 4 comes before 1-3 in Jeppe’s useful schema. Members of political societies draw on reasons that are embedded in (their individual awareness of) their life narratives and particular circumstances. These reasons are rooted deeply in the members’ local knowledge of their particular practices, aims, patterns, beliefs, and much else; and are often reasons for them precisely due to the particulars. (Here, incidentally, there might be an interesting cross-pollination between Jerry’s focus on convergence and MacIntyre’s focus on narrative.) It is far from obvious, at least, that members of political societies may not permissibly rely on these particular reasons, even if some of the reasons are not ‘public’ in the sense of being publicly accessible. But, consider: If a plausible view of public reason permits reliance on these reasons, this is striking because the reliance is often in error. For we are, to no small extent, ‘opaque to ourselves.’ If so, then even convergence itself, which is less epistemically demanding than consensus, might yet be too demanding to justify a set of social or political rules if it is, in whole or part, convergence on these particular reasons.

A good countermove here, which Jerry illuminatingly explores in OPR, is to moderately idealize citizens. The aim is to eliminate these epistemic issues perhaps by idealizing agents’ reasoning but not their reasonably chosen ends. Notice what happens, though, if such idealization ends up, as it might, being either unjustified on reflection or justified but unable to eliminate all errors that warrant elimination. The required form of mutual endorsement would then rest largely on agents’ lack of knowledge of both their particular circumstances and the self that navigates those circumstances. What we would get is an inadequately informed act of the will (endorsement) or formation of beliefs (usually, un-willed objects of potential convergence) on the part of members of a political society that are not clearly sufficient for convergence. If reflection confirms they are not, then a key issue for convergence theorists would not necessarily be that convergence itself fails as a moral criterion of justification, but (at least) that theorists and social scientists face large epistemic obstacles in knowing when convergence obtains, if ever.

Why might this matter? It matters, or so I believe, because it might make us uneasy about a claimed moral criterion whose presence or absence we cannot reliably detect. Two questions then: (1) If moderate idealization is required to avoid the so-called empty set objection, viz. that no political arrangement will end up being endorsed, how could we detect in practice when the idealized convergence would obtain? (If we could detect it, that’d give us helpful data for reflective equilibrium theorizing. Lacking that data, we should presumably assign lower credences to our claims.) And (2) if Jeppe’s question 4 really is fundamental, does it matter if detection is unlikely or even predictably impossible? Both questions seem to me worth exploring.

First, I forgot to convey my gratitude to Chad for his part in organizing this symposium. I apologize for my forgetfulness – thank you, Chad! Working on Gaus’s article and thinking about his reply has been fun and interesting, so I’m truly (and ungrittedly) grateful to all.

Second, I’d like to make another case for the search for consensus as a sensible second-order project and thereby explore the disagreement between Gaus and Rawls. In my comment, I suggested that Gaus offers few reasons for the claim that the Rawlsian search for consensus is misguided. Gaus’s reply didn’t add such reasons – which is fine, given that he also specified that the main purpose of the essay is to provide proof of concept that diversity can counteract the centrifugal power of diversity. But Gaus’s elaboration of his disagreement with Rawls opens new questions:

“[The Rawlsian project] fails because it seeks the second-order theory via consensus. […] In terms of Figure 1, Rawls aimed at state W, where we agree about justice. That is fine for a first-order theory (why not “create” a well-ordered utopia?), but it undermines contractualism’s claim to be an effective way of reconciling conflicting first-order judgments (aka “theories of justice”). Rawls came to recognize this, and point W essentially vanishes in his final analyses. Still, his commitment to consensus makes rightward movement on the x axis difficult: point B probably already is a move too far.”

I’m not interested in assessing the accuracy of interpretive claims about the development of Rawls’s philosophy (well, I am interested, but not here). Yet the quoted comment does not explain what’s wrong with investigating what sorts of theories of justice we can all agree to. I also believe that the comment conflates two different second-order projects. Rawls’s project is to investigate and clarify an ideal of democratic society and thereby find the normative requirements shared by those committed to this ideal. Gaus’s project is to investigate how we can live by shared rules in the face of deep and intractable disagreements. These are not mutually exclusive projects, though they may issue contradictory requirements.

As I understand it, the central Rawlsian question is what conception of justice is most suited to the ideal of democratic society as a system of cooperation between free and equal persons. In TJ, Rawls argues that justice as fairness answers this question. In later writings, he revises justice as fairness and elaborates the argument for it, but also allows that other conceptions of justice can claim to express and satisfy the ideal of democratic society – hence the “family of liberal conceptions.” But this family shares a set of properties that any theory of justice must possess in order to serve as a satisfying interpretation of the normative commitments of the ideal of democratic society. To be clear, there is:

I. A question: what is the best conception of justice for a democratic society?

II. A method: identifying the values and commitments of the ideal of democratic society, and using them to rank candidate conceptions of justice (here the OP device offers a helpful sorting tool).

III. An answer: justice as fairness is the best conception of justice for a democratic society. Other conceptions of justice from the family of liberal conceptions also satisfy and express the ideal of democratic equality (so, they might not be “best”, but they’re good enough).

IV. Normative implications for what we (those committed to the ideal of democratic society) should do in terms of constitutional design, choice of economic system, and so on.

And there are further questions about stability and legitimacy; hence, PL.

It seems to me that Rawls’s question is worth thinking about, his method suitable for it, and his answer well defended; even though it is a search for consensus among those who share a commitment to democratic society, but disagree about what this commitment entails in terms of principles of justice.

Now, Gaus might object that this is all first-order theorizing and so in the realm of what he takes as input for the reconciliation project. That is, I.-IV. above do not answer the question of what we should do in the face of deep and intractable disagreement about justice. But doesn’t it? Assuming that we agree on the ideal of a democratic society, it settles the range of reasonable disagreement and the procedures for dealing with reasonable disagreement. As long as we agree on the constitutional essentials, there is no need for convergence – it’s fine if we disagree about whether to pursue the difference principle or restricted utility, as long as we agree on the democratic constitution that defines the procedures for making (and changing) the choice.

What if we disagree about the ideal of society? What can the person committed to democratic equality say (and do) to the person committed to an aristocratic or theocratic ideal of society? Or what can a Rawlsian say (and do) to a socialist who rejects the Rawlsian interpretation of democratic equality? That’s a different and also interesting question. And if different ideals support different principles of justice – as seems likely – then the presence of such disagreements makes questions of legitimacy all the more important, since it requires us to think about the permissibility of forcing others to live in accordance with an ideal of society they reject.

So, the search for consensus aims to answer an interesting question, and it can, I think, be pursued without answering the question of reconciliation (so, I’m unsure about Greg’s suggestion that the fourth question is fundamental). The search for convergence might be necessary to answer a different interesting question, but I see no reason to assign priority to either of the questions.

Interestingly, though, the search for consensus and convergence both produce requirements of justice governing the same subject of justice, inviting the further question of what we should do when these requirements contradict each other. Rawls argues that the ideal of democratic society is satisfiable only by left-liberal principles of justice and the institutions that express these. Gaus argues that the conditions of convergence are articulated by right-liberal principles of justice and the institutions that express these. It may be that Rawls’s argument shows that the ideal of democratic equality is realizable only in a socialist system (as Bill Edmundson argues quite persuasively in John Rawls: Reticent Socialist), whereas Gaus’s argument establishes that the conditions of convergence are secured only in a free-market capitalist system (as Gaus suggests). If so, we have yet another kind of disagreement about justice.

Hello, and thank you for the opportunity to join this discussion. A word of introduction; I’m a newcomer to philosophy, having had a career in the business world as a specialized sort of technical writer. I’ve been working with Jeppe for the past six years, first as a student, then as a research assistant, and latterly as his editor. As such, I am familiar with much of his more recent work on Kant and Rawls, but I am less familiar with the ongoing discussion of these matters by others.

My preference is always for thoughts grounded in action, and my questions are two:

First, does not convergence – the desire to join with others in a mutually beneficial society even if there are substantive areas of disagreement among us – become itself a moral demand? I worry that if it does, then this has troubling implications. It seems to me that one could plausibly say, “The change you wish to make is just, but would disturb too many people to be permitted.” In other words, if the demand to achieve and remain reconciled overrides other elements of morality, such as justice, this might be more dangerous than irreconcilable differences.

But second, can there be any real change without the process of seeking justice, developing diverse and conflicting views, and then moving through those diverse views (not without pain) towards or away from convergence? I am thinking, in this regard, of the Grimké sisters, whose outrageous demands for justice in the 1830s and 1840s – the abolition of slavery, political and social liberty for women – read to most of us now like plain common sense. Some today would still find their views unacceptable, in whole or in part, but I think we might agree that their histories and others like them show that the search for justice sense is a trigger for change, where convergence is both a result and a new starting-point.

This strikes me as in some ways a Hayekean process – it’s slow, it’s conditioned by local knowledge and conventions, but it’s also essential to social survival. In other respects, however, this process seems to me to be Rawlsian; it addresses change in institutions as matters of justice based on an ideal of democratic society, not of seeking agreement in diversity. I don’t see how we can maintain the creative tension between ideals and realities without both.

References

Whipps, Judy, (no date given) “Sarah Grimké (1792 – 1873) and Angelina Grimké Weld (1805 – 1879)”. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (https://www.iep.utm.edu/grimke/) The Grimké sisters occur to me as an example because a bridge is being renamed in their honor near their home in Hyde Park, Boston, MA.

Thanks to everyone for their comments. I avoid point-by-point replies — not because there aren’t many interesting points, but point-by-points are not very interesting to read (I have been able to talk to Keith about his insightful comments). Besides, we want a conversation, not a Q&A session. So just two points.

1. In developing any model it is absolutely critical to keep in mind what we are interested in modeling. It is surprisingly how often a model does one thing and then, in the interests of “realism,” adds things that are orthogonal to the point of the model. Models are tools to help us in our thinking; we only want a fancy tool when a simple one won’t do. My concern here was to take something similar to Rawlsian “reasonable agents,” and instead of devising a contract, let them interact on their own, moral, terms. To do that, we wouldn’t want to add self-interest any more than, in the original position, we would want people to have a peek of what their actual positions really are. What I was trying to do is sketch an alternative to social contract thinking, which took as its point of departure moral disagreement. It is a view of how we might think of resolving these disagreements without a “contract,” not predicting what would happen in actual systems.

This is not to say that an interesting model of moral choice might not reconsider the relation of self-interest and morality. A fundamental philosophical question is whether we should sharply distinguish “moral” and “self-interested” motivations. The whole idea of the Rawlsian set-up is to distinguish these, separating out the “rational” from the “reasonable,” with the former being defined in terms of interests and the latter about impartiality. Perhaps, though, what one thinks is the proper moral theory is, to some extent, inherently about what advances one’s good, so “the rational” and “the reasonable” are inherently intermixed. Maybe moral choice itself always reflects some vector of these. I believe the experimental evidence supports this hypothesis. I am now working on models in which one’s understanding of “reasonable impartiality” is a way to advanced one’s “interests.”

2. Again, the point of the paper’s model is to take morally diverse agents and see how, given their different moral views, they could manage to reconcile on a shared morality. I have called this a second-order moral theory.

So why don’t I think that the contractualist project is a plausible route to a second-order moral theory? Because, frankly, in the guise of a theory of “what we could agree to” it becomes a normalization project in which the “we” is a constrained to an approved part of the moral/ideological spectrum. Jeppe seems to assume that “we agree on the ideal of a democratic society.” But we do not agree on any such thing. Certainly most believe that regular elections with universal suffrage is better than the other feasible alternatives, but that it hardly an agreement on the sort of society “we” want. “We” — if we mean the overwhelming majority of good-willed citizens in the modern world — manifestly do not agree on any ideal of society or conception of justice. An ideal not only enumerates values, but orders them, and good-willed people do not agree on any ordering, and so we do not agree on any conception of justice. “We” do not agree on justice as fairness, prioritarianism, welfarism, libertarianism, secularism, or the importance (indeed validity of) of distributive justice. Any attempt to bracket what we disagree about and model a second-order morality on the core — what “we all agree” about — is inevitably an exercise in some folks simply being normalized out of the problem, or told that they “really” agree on a view they adamantly reject. The world of academic philosophers is immersed in WEIRD morality, and they think that everyone (who counts) agrees with them. So far from everyone agreeing, the empirical evidence is that, overwhelmingly, most in the world disagree. It is totally sensible to for philosophers to explore controversial (first-order) theories of justice: it is hopeless for them to explore such theories under the guise of discovering “what we all agree about.” Once Rawls saw that the burdens of judgment apply to justice the game was up: and it was all patches and hand-waiving from there on. When I read the unfinished draft of the revised version of Political Liberalism, it seems manifest that the project was falling apart.

So far from a constitutional consensus being support for Rawlsian project, it seems to me to lead to a convergence analysis. A consensus on the rules of interaction is precisely what the model was seeking to examine, and for that a deeper consensus is not necessary. And the interesting idea I explored in the paper: it can be a hindrance.

One more note on the Rawlsian project.

As I understand it, the Rawlsian project is not to make sense of an ideal of democratic society that all (actually, hypothetically, or normatively) agree to. The project, rather, is to make sense of (and understand the principles of justice implied by) an ideal of democratic society that many find appealing, and which many rely on when they think about justice and criticize and justify political choices, even though the ideal itself is hard to state clearly. Thus understood, Rawls’s argument does not move from contractualism to the ideal of democratic society; instead it moves from the ideal of democratic society to contractualism.

The argument isn’t mere conceptual analysis, for the ideal is drawn from and elucidated via the history of ideas and the self-understanding of liberal democracies implied by various key texts, and the hope is, of course, that the ideal is widely shared. Even so, the scope of the ‘we’ is limited to persons who share the ideal of democratic society understood as a system of social cooperation between free and equal persons.

Some persons do not share the ideal – they might reject democracy or the understanding of democratic society as described above. Some who share the ideal disagree with Rawls’s argument that justice as fairness is the conception of justice best suited to it. And there might be further disagreements among those who accept both the ideal and the principles of justice as fairness, but disagree about further details; e.g., disagreements about what rights should be included in the first principle, whether the difference principle is superior to alternatives, and whether capitalism is compatible with democratic equality, and so on. These are different sorts of disagreement and pose different challenges to the Rawlsian project.