Options Without Constraints

Options Without Constraints

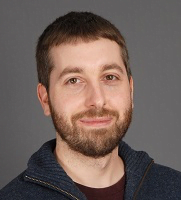

Richard Yetter Chappell

The paradox of deontology counsels against including constraints in our fundamental moral theory. Consequentialists are generally suspicious of the associated asymmetries, e.g. between doing and allowing, or killing and letting die. We say you should just bring about the best outcome, counting any harms done along the way just as we count any harms thereby prevented or averted. Without constraints, it is possible to justify acts that involve killing or otherwise harming as a means so long as the outcome is sufficiently good.

Ordinarily, though, we don’t think that people are strictly required to do only the very best of all the possible actions available to them. A more lenient approach, granting agents options to do less than the best, seems more reasonable. Suppose that you’ve already generously donated half of your income to charity. If you could save an additional life by donating $4000 more, it’d be great to do so, but surely isn’t strictly required. In this context, we’re inclined to think, you may reasonably prioritize your finances over another’s life (despite the latter being objectively more important).

Such options are awkward to combine with the rejection of constraints. If you can permissibly prioritize $4000 for yourself over a stranger’s life, and there’s no constraint against harming as a means, it would seem to follow that you could permissibly kill a stranger to get $4000. But that’s abhorrent. (Mulgan 2001; cf. Kagan 1984, 251)

Fortunately, I think the satisficing view defended in my 2019 provides us with the resources for a compelling response to this problem. The relevant feature of the view (for present purposes) is its sentimentalist understanding of obligation in terms of blameworthiness, which in turn is understood in terms of quality of will. Very roughly, acts are impermissible when they reveal an inadequate degree of concern for others.

Now, there are features of human psychology that can explain why (harmful) killing typically reveals a worse quality of will than merely letting die. The relevant psychological facts concern what we find salient. We do not generally find the millions of potential beneficiaries of charitable aid to be highly salient. Indeed, people are dying all the time without impinging upon our awareness at all. A killer, by contrast, is (in any normal case) apt to be vividly aware of their victim’s death. So, killing tends to involve neglecting much more salient needs than does merely letting die. (There are exceptions, e.g. watching a child drown in a shallow pond right before your eyes—but those are precisely the cases in which we’re inclined to judge letting die to be impermissible, or even morally comparable to killing.)

Next, note that neglecting more salient needs reveals a greater deficit of good will (Chappell & Yetter-Chappell 2016, 452). This is because any altruistic desires we may have will be more strongly activated when others’ needs are more salient. So if our resulting behavior remains non-altruistic even when others’ needs are most salient, that suggests that any altruistic desires we may have are (at best) extremely weak. Non-altruistic behavior in the face of less salient needs, by contrast, is compatible with our nonetheless possessing altruistic desires of some modest strength—and possibly sufficient strength to qualify as “adequate” moral concern.

Putting these two facts together, then, secures us the result that harmful killing is more apt to be impermissible (on a sentimentalist understanding) than comparably harmful instances of letting die. It’s a neat result for sentimentalist satisficers that they’re able to secure this intuitive result without attributing any fundamental normative significance to the distinction between killing and letting die. We thus find that consequentialists can allow for options without constraints after all.

[The full version of this argument will appear in ‘Deontic Pluralism and the Right Amount of Good’, forthcoming in D. Portmore (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Consequentialism. OUP.]

Hi Richard

interesting. There seems to be an assumption in the beginning that rules out a simpler response and so I was wondering why have that assumption.

In the beginning, you write that “Consequentialists are generally suspicious of the associated asymmetries, e.g. between doing and allowing, or killing and letting die. We say you should just bring about the best outcome, counting any harms done along the way just as we count any harms thereby prevented or averted”. I know that there are consequentialists who think this, but this doesn’t seem to be a necessary feature of consequentialist views. As it has become evident in the recent consequentializing debates, there are forms of consequentialism that have agent-relative axiologies and on these theories it is also pretty easy to recognise things like doing and allowing and killing and letting die in the axiologies so as to create constraints (via certain kind of value and disvalue of the agent’s agential involvement).

If we do this, it seems hard to see how there could be a conflict between recognising intuitive options and constraints. Say that we have an agent-relative evaluative ranking of an agent’s options in some situation. Now, this ranking could rank the agent actually doing harm very low relative to the agent exactly for the kind of reasons you explain – relative to the agent the outcome in which he or she has acted from a bad will that doesn’t give sufficient weight to the needs of the victim is really bad. In constraint cases, this outcome can be bad relative to the agent even if it would better agent-relatively than some other outcome (in which many more others act from bad will for example). Yet, with the agent-relative ranking, the view can create agent-relative options at the same time with the higher-ranked options (by, say, satisficing, coarse-grained axiologies, dual-ranking, valuable option-sets etc).

So, it looks to me that (agent-relative) consequentialists can easily find room for both options and constraints at the same time if they so wish. They could equally find room for only options or for only constraints. Also, given your own quality of the will view, it doesn’t seem like this even requires making the doing/allowing distinction fundamental normatively speaking – maybe quality of the will is and that grounds the former distiction. But, is the idea that we have to give up the constraints just because agent-neutral commitments of consequentialism but we can still use the quality of the will story to make this more intuitively acceptable (there is a different sense in which it is wrong to kill)? If this is right, I think I would rather just give up on agent-neutrality.

Hi Jussi,

I’m more just presupposing that rejecting constraints is an attractive theoretical position, along with accepting options, and then trying to show how we can combine the two without falling afoul of the Kagan/Mulgan objection. If you don’t see any antecedent appeal to traditional consequentialism then I don’t expect this post to change that.

Why don’t I prefer “consequentializing” instead? At heart, the proposed axiology, attributing extra *disvalue* to things like agential intervention, just strikes me as wrong / unappealing. (I’m fine with agent-relative *welfarist* values, by contrast. So it’s not neutrality that’s at issue, but rather whether you seem to be implicitly building in deontological values, leaving us with a view that is “consequentialist in name only”.)

Hi Richard

thanks – that’s very helpful. I guess my question is the following. You give a very eloquent story about what bad will is and how it differs from morally decent willing. You then use this wonderful story to explain why doing certain actions is wrong in the sentimentalist sense and use it also to make sense of blameworthiness. However, what if I was so impressed by the account that I in addition just adopted the account in my standard agent-relative axiology as one of the things that makes an action bad relative to me (that it’s done from the kind of will you have colourfully explained)? If you are right, it then turns out that oftentimes when there are questions of doing and allowing, killing and letting die these differences can often be accounted for in terms of the differences in the quality of willing.

In this case, I haven’t adopted an axiology that attributes extra disvalue to things like agential intervention. And, if I generate options with satisficing or some other means, I don’t get the Kagan/Mulgan problem. Furthermore, I also seem to get constraints as sometimes I ought to do things that are not agent-neutrally the best even if we think that acting from a good will is agent-neutrally also good and acting from a bad will agent-neutrally bad. And, I seem to get a view that extensionally comes close to acknowledging doing and allowing, killing and letting die differences even if it doesn’t recognise them at the fundamental level of axiology.

So, I was wondering what the problem is with this alternative. It can’t be neutrality as you say, and it cannot be wrong/unappealing axiology either. Perhaps it is that rejecting constraints is attractive in its own right, but I’m not quite sure why. Maybe it is the antecedent appeal of traditional (agent-neutral) consequentialism, but I’m not quite sure what that is (and neutrality was not supposed to be the issue and that’s the only thing I’ve given up on).

Ah, okay, so the question is whether we should attribute disvalue to acting with ill will? You certainly could do, like Hurka on vice. I guess it just comes down to your substantive judgment regarding what you think ultimately matters, or is worth caring about. I’d be open to attributing some slight disvalue to vice or ill-will (though whether it’s acted upon or not doesn’t seem so relevant to its intrinsic badness, IMO), but it seems to me that it should largely be swamped by the importance of welfare when the two come into conflict.

Note that this wouldn’t introduce constraints in the ordinary sense, since welfare-maximizing acts can (presumably) always be done with good will (even if someone is harmed, their interests aren’t necessarily *neglected* if others are benefited more).

And I don’t even think it’ll be very helpful for distinguishing between intuitively “permissible” and “impermissible” *suboptimal* acts (as discussed in the OP), at least without giving an implausible amount of weight to this value, since the disvalue of someone dying unnecessarily should (IMO) completely swamp the disvalue of acting with a bad will. So if the former is insufficient to make charity obligatory on our satisficing account, it would be surprising for the addition of the tiny disvalue of a bad will to suddenly make all the difference. So I don’t think this move could substitute for the account I offer in the OP. We need to look elsewhere than value in order to solve the Kagan/Mulgan problem in a plausible way.

Alternatively, if you assign massive weight to the disvalue of the bad will, then I think you’re back in “wrong/unappealing axiology” territory. Even if welfarism isn’t strictly correct, it at least strikes me as identifying the core of what matters most. So any supplemental values shouldn’t lead us *too* far away from welfarist verdicts.

@Jussi Suikkanen:

“In the beginning, you write that “Consequentialists are generally suspicious of the associated asymmetries, e.g. between doing and allowing, or killing and letting die. We say you should just bring about the best outcome, counting any harms done along the way just as we count any harms thereby prevented or averted”. I know that there are consequentialists who think this, but this doesn’t seem to be a necessary feature of consequentialist views. ”

I… don’t get it. It’s not just a necessary feature of consequentialist views, it’s the definition of consequentialism. Axiologies just change valuations, so they can’t introduce the assymetries that constraints do. Any consequentialist still tries to bring about the best outcome.

Thanks for your interesting post. I find myself wondering if you have views about which understandings of the quality of the will are compatible with an overall consequentialist view. If a person maintained that the quality of the will is determined, for example, by the universalizability of the agent’s maxim or by conformity to God’s law would the result still count as an instance of Consequentialism?

You /can/ of course impose a constraint by applying a valuation to a /word/. Like, “I value not murdering.” But that’s not applying a valuation to a world state, which would be something like “I value people remaining alive”. Hiding ethical constraints inside of how you define words is just erroneous philosophizing. Consequentialism = best outcome = best world state. Changes to valuations based on how you got to that world state are non-consequentialist by definition.

Er, I stated that wrong. I don’t mean the ends justify the means. I mean that the words you use to describe your path through world states have no ethical weight. Nothing that is not a consequence has ethical weight. In particular, “agency” is close to “causation”, which is a purely metaphysical and unobservable construct (as argued by Hume). So anything which incorporates agency (e.g., who did it) into values isn’t consequentialism.

@David Sobel: If a person maintained that the quality of the will is determined by the universalizability of the agent’s maxim or by conformity to God’s law, I think we could call that Consequentialism only if those laws used only words that were operationally defined. It isn’t consequentialism if ethical rules are encoded into how we define our terms. If God’s law says “Honor thy father and thy mother”, it’s embedding the non-consequentialist assumption that the person who does the honoring is a factor in the goodness of outcome. You could argue that it does affect the consequence, as parents will be more pleased at being honored by their children than by strangers, but I would reply that you were just saying that the emotional bonds between the involved parties, rather than the clinical terms “your father” and “your mother”, are the things that must be incorporated into the valuation.

Emotional bonds are, of course, difficult to operationalize. In practice, we end up using facts like kinship as proxies for them. But the more such proxies or non-operationalized terms there are in a system of ethics, the less pure consequentialist it is.

This all strikes me as a very rationalist approach to ethics, as if we were all perfect reasoners with infinite computational power, and treated each “person” as having equal value. But evolution doesn’t produce such people. It is quite impossible for any species to evolve which is non-competitive, and thus it is impossible for any evolved being to have instinctive ethics that treat all members of the species as having equal value.

You can talk about the ethics that humans have evolved, in which case you’re going to end up doing descriptive rather than prescriptive ethics. Or you can talk about the ethics that would work best for some real human society, implemented by people of ordinary intelligence (not smart enough to be consistently effective consequentialists). But talking about the ethics that would work best for perfect rational reasoners with infinite computational power, using a set of egalitarian values which no life form can possibly evolve, will lead you into contradictions with both the ethics you feel inside you, because humans have evolved to react in certain ways to particular stimuli (rather than to outcomes), and with any pragmatic, usable system of ethics.

Hi David! Yeah, I think our understanding of quality of will should reflect our normative commitments. So a utilitarian, for example, should think of quality of will as basically a measure of one’s beneficence. Consequentialists more broadly may understand quality of will in terms of desiring those things that are basically good (which presumably includes each person’s wellbeing, but perhaps some other things too).

If one had a wildly different understanding of quality of will (involving respect for rights, etc.), it wouldn’t mesh well with a broader consequentialist theory, e.g. of how to morally rank one’s options. I take it that we want good quality of will to be compatible with performing the morally best action (putting aside weird cases where bad motives would themselves have great instrumental value, perhaps). So that will put constraints on which views can coherently be combined here.

I spoke incorrectly: It is possible for a nearly non-competitive species to evolve, if there are so many other species competing for the same resources that competition with other members of its own species are negligible, or if group selection works in a way that requires it to sometimes cooperate as an equal partner with all other members of the species it encounters (as do the reproductive methods of some Dictyostelium species). Members of a species can also evolve to be non-competitive in particular contexts, as in bacterial swarming behavior. But none of this seems likely to ever be relevant to life intelligent enough to contemplate ethics.

Hey Richard,

Your reply makes very good sense to me. But then I wonder about the compatibility of consequentialism and the understanding of the quality of the will you rely on. Offhand it feels like the quality of the will account you offer is responsive to a commonsense understanding of the quality of the will rather than a distinctively consequentialist understanding.

Hi Philip, I don’t take normative ethics to primarily concern “the ethics that would work best” — that just sounds like an empirical question to me (assuming we have a shared understanding of what goes into evaluating an outcome as “best”). There are interesting questions about how the best code to follow relates to what we *really* ought, or have reason, to do. But our topic is the latter, not the former.

(fwiw, my view is that — contra rule consequentialists — there is no necessary connection between the two. It’s possible that the most useful code might direct us to do terrible things that there is no real reason to do, e.g. if it is useful for extrinsic reasons, unrelated to the actions it directs us to perform.)

Hi David, insofar as I didn’t build in anything but “altruistic” (i.e. beneficent) desires to my understanding of quality of will, I think it should be compatible with consequentialism (and indeed with utilitarianism in particular). The rest invokes commonsense psychology (e.g. concerning the interplay of salience and desire) rather than commonsense morality, so again I wouldn’t expect any problems here. But perhaps I’m missing something?

I would have thought you built in a particular understanding of what makes a will more or less beneficent that relies on aspects of commonsense psychology. But I don’t see how that understanding of what is more and less beneficent is compatible with consequentialism. And the psychology, as I understand it, that you rely on is descriptive. I don’t see how the normative thesis about what counts as more or less beneficent or a better or worse will fits well within a consequentialist framework.

What makes it more or less beneficent is (what the act reveals about) the strength of the agent’s beneficent desires. Descriptive psychology is playing a purely descriptive role, of helping us to accurately identify when agents have more or less strong (background) beneficent desires. In particular, I rely upon the idea that one could have moderately strong (background) beneficent desires that simply fail to be “activated” as strongly by less salient needs. That’s the descriptive claim. My crucial normative assumption is that *possessing* suitably strong beneficent desires, whether they’re strongly activated in the moment or more dormant, is what matters for our normative assessment of the agent.

One could certainly question the latter assumption — you might argue that it’s the strength of activation, rather than the background strength of the desire, that is normatively relevant. That’d be interesting to explore more. But I don’t see that consequentialism per se forces us in either direction here.

To test the “fit” with consequentialism: Can you think of cases where my account of quality of will would preclude a “good-willed” agent from doing the morally best action (as we would find with, e.g., a rights-based account of the good will)?

We might imagine cases where to do the most good you must prioritize distant needs over salient ones (let a child drown to donate money that would save five, say). But nothing in my account says that we *must* respond more strongly to salient needs, just that it’s typical (so saving the one, while suboptimal, needn’t entail a *lack* of concern for the others). If an agent manages to work up enough impartial concern to save the distant five over the nearby one, that likely demonstrates extremely strong beneficent desires (good quality of will on my account). The primary exception would be if they only achieved this due to a problematic lack of concern for the one (suppose racism or xenophobia led them to actually not care about the one’s wellbeing at all).

I’m sure I’m failing to get a lot that is going on here. I suppose one question I have is what generates the rankings of quality of will. You wrote “neglecting more salient needs reveals a greater deficit of good will”. That made me think that the person who is equally responsive to the well-being of distant strangers as to locals will have a lower quality of will. That struck me as in tension with a consequentialist approach, but again, as I say, I would not be at all surprised if I am missing stuff in the background of your view. Real philosophical communication is weirdly difficult. Thanks again for a very thought provoking post.

Ah, right, sorry for my lack of clarity there. Interpret “neglect” as giving less weight to the person’s interests than utilitarianism calls for. So being equally (positively) responsive to everyone’s interests does not involve neglecting anyone, so doesn’t involve any ill-will.

To further clarify the quoted passage: neglecting more salient needs reveals a greater deficit of good will just because (and insofar as) it reveals a greater deficit of beneficent motivation. Even very minimally altruistic people will likely feel motivated to help a child drowning right before their eyes. So someone who won’t help others *even when their needs are extremely salient* must be extremely lacking in altruism (or at least so it would be natural to conclude — it’s not a strict entailment).

Richard, re your statements, “There are interesting questions about how the best code to follow relates to what we *really* ought, or have reason, to do”: This seems to me to be an uninterpretable statement. To a consequentialist, “the best code to follow” is that which produces the best results, which would be that which we really ought to do. I strongly suspect you’re using “ought” to introducing some metaphysical notion of value.

Re. “the most useful code might direct us to do terrible things that there is no real reason to do, e.g. if it is useful for extrinsic reasons”: Extrinsic to what? How can extrinsic reasons be reasons when you just said they’re not real reasons? No reason is extrinsic to ethics.

The page you linked to to explain extrinsic reasons is about how to endorse behavior that isn’t strictly rational on the grounds that the rational approach may be “unreliable”. If by “unreliable” you mean high-variance of outcome, then that’s just an argument over average consequentialism vs. other utility functions. If you mean the agent will on average get a worse outcome than with some other approach, I don’t see how that helps explain what you mean by “extrinsic reasons”.

Hi Philip, suppose that an evil demon will destroy the world unless I internalize a moral code that directs me to kick puppies. (The demon doesn’t care whether I actually end up kicking any puppies though, he just wants me to internalize the code.) That is then the best code for me to internalize (doing so saves the world!), but it directs me to performs acts (kicking puppies) that are in no way good, or worth doing. That’s an example of what I mean by a code being good for ‘extrinsic’ reasons (which is compatible with there being no reason to perform the *actions* recommended by the code).

Happy to discuss this more in comments to the linked post, if you wish. But it’s taking us a bit far afield from the PEA Soup topic.

Hi Richard,

Huge fan of your satisficing paper, very excited about this application! It sounds like your view will handle lots of ordinary cases. But I wanted to push back on a few points. (I realize I’m late to the party, here, so no obligation to respond.)

1. On your view, a child dying right in front of you is salient, and so you suggest that letting him die might feel “comparable” to killing him. I don’t feel that way. Suppose I am choosing between saving a child right in front of me or two distant strangers (my scarce drug is more effective among a certain distant group). Nothing wrong with saving the two. But I feel it would be horribly wrong to save them by *killing* an innocent child.

(I know you didn’t have this sort of thing in mind; you just meant that failing to save the drowning child feels wrong, like killing. But it’s worth pointing out that there are other respects in which the killing isn’t intuitively comparable.)

2. What about killing non-salient beings? Do you think this tends to be about as permissible as letting them die? (Or more permissible than killing people in front of you?) My sense is that I would be wrong to kill even one distant, anonymous stranger in order to save my little brother, though it would clearly be permissible to use my scarce drug to save him rather than five anonymous strangers (or for that matter, five familiar acquaintances).

The point of 1&2: killing often feels wrong even when the person killed isn’t salient, and letting die is often fine even when the forsaken people are salient. Killing/letting die doesn’t line up quite right with salient/non-salient victim. I’m sure this isn’t news to you, but like I said, just offering push-back!

3. Do deontologists really think that killing/letting die matters *fundamentally*? Maybe Ross did, but I don’t. Killing is only worse because we have rights against it, a bit like if we all promised not to kill each other (without promising to save each other). That’s why killing/letting die is screened off by valid consent — something that Ross’s view ignores, with its brute split between beneficence and non-maleficence.

Thanks Daniel, that’s interesting stuff!

I agree that salience won’t perfectly track pre-theoretic intuitions about killing vs letting die, so my view will (like any form of utilitarianism) end up being somewhat revisionary. I’ve argued that these moves can help us a fair bit (esp. in ordinary cases), but it’s certainly an open question whether that’s *enough*, or whether intolerable implications remain. So let’s try to pin down a concrete case of non-salient killing, to see.

One tricking aspect of this is that many people’s psychologies might be such that they would find almost any killing to be salient, even if the victim is anonymous. The agent might dwell a lot on the fact that they’d caused this great harm to some (unknown) other(s), or at any rate, the reality of the harm would be much more striking to them at the time of choice than a comparable “letting die” would be. So we need to stipulate in our case that our agent is *not* like this. They really think no more about the distant killing than they’d think about a distant letting-die. Maybe a case involving a form of air pollution could help make this plausible, as people actually often pollute without giving much thought to the eventual harms this causes.

Suppose that saving your little brother would (for some reason) entail releasing a weird gas into the air. The gas would have no local effects, but instead float around in the atmosphere for a while until it reaches a distant country, at which point it would home in on a large population to ensure its efficacy. The effect would be to slightly raise the rate of respiratory illness in the population. While we couldn’t identify any particular victim of the gas, we could expect X (1, 5, whatever) more deaths in this population from respiratory illnesses that winter than would otherwise have occurred. So, while the causal chain is all a bit convoluted and indirect, I take it we can classify the release of the gas as a form of “killing”, in the sense that it causes these extra deaths to eventually occur.

Is it wrong to save your little brother in this case? Deontologists will presumably think so (as may maximizing utilitarians, depending on the value of X). Pre-theoretic intuitions might lean in that direction too, but I think much less strongly now than in the standard Kagan/Mulgan cases that we started with. So it seems to me a tolerable bullet for the satisficer to bite, to allow (a limited number of) such non-salient killings. But others may disagree, so it’s certainly worth making the theoretical costs of the view clear.

re: 3: Aren’t rights a way of talking about what’s of fundamental (or non-derivative) significance? E.g. if you’ve a right not to be *killed*, rather than just a right not to have your *interests be unduly neglected* (or some such), then that still sounds to me like a way of attributing non-derivative significance to killing. Unless perhaps there’s some further story to be given about why there’s a right not to be killed, which makes it seem more derivative in nature (like in your promising example)? I take it that significance can be non-derivative even if conditional (e.g. on not being waived), after all. But you may be right that fundamentality isn’t the real issue here. Perhaps I’d do better to frame it in terms of whether killing *per se* is what carries normative weight, or just something that’s *correlated* with killing (e.g. salience).

Richard, thanks for the very thoughtful reply. What you said about salience, intuitions, my little brother, etc. all sounds quite reasonable.

On rights and killing: now I see what you mean! Killing does matter per se to deontologists who think that it’s a basic fact about our rights that we have rights against being killed but not against being allowed to die. There’s no deeper explanation for them than the nature of killing— maybe plus the idea that killing is a bigger blow to dignity, autonomy, or what have you.

My own hunch is that rights don’t work like this. Killing only morally matters because we have rights against it, and we have rights against it, and not against being allowed to die, because it’s not practical for a society to forbid all acts that result in more death. We have to forbid selectively, and killing is a smart thing to select: easy to spot, not too common, not too tempting, not too hard to enforce a ban. (Not that anyone had to deliberately work all this out.)

So I agree with consequentialists that nice distinctions between causal means shouldn’t *intrinsically* matter, but I think some of these distinctions have been picked up by social institutions: they’re encoded in law and part of informal morality.

Anyway, I’ll leave it there, before I out myself as a total oddball deontologist. Thanks again for the post!

Killing will involve neglecting a lot more critical needs than does only letting die. Putting these two facts together secures us the result that brutal murder is more apt to be impermissible than comparably severe cases of making die.

Salvador: if the death is similar in both cases, why think the killing neglects “a lot more critical needs?”

Compare:

1. You need to breathe, and you’re trapped in a room with no oxygen. I could pump in some oxygen by pressing a button — but I don’t, and you die.

2. You need to breathe, and you’re trapped in a room with plenty of oxygen. I can suck it out by pressing a button — which I do, and you die.

What needs of yours do I neglect in the killing case alone?