Consider a father who looks at his beloved daughter and thinks, ‘What I want most in life is just for you to be happy.’ In thinking this thought, the father makes use of a concept that is deeply important but also very difficult to adequately characterize – the ordinary concept of happiness. Our aim is to understand how this concept works.

One obvious view would be that the ordinary concept of happiness is just a matter of having certain psychological states. For example, it might be thought that the ordinary concept of happiness is a matter of feeling good, experiencing satisfaction with one’s life, and not experiencing negative affective states, such as pain, lonelinessor despair. On this view, when the father thinks that what he wants most in life is for his daughter to be happy, what he means is simply that what he wants is for her to have certain kinds of psychological states.

An alternative possibility is that the ordinary concept of happiness is something more normative. On this alternative, the concept is not just a matter of having certain psychological states; it also has something to do with having a genuinely good life (see, e.g., Annas, 1993; 2011; Foot, 2001; Kraut, 9179). The most extreme version of this second view would say that the ordinary concept of happiness simply is the notion of well-being.

So which of these two possibilities better captures what the father is thinking about his daughter in our example? Is the ordinary concept of happiness really just concerned with the psychological states one experiences, or is it normative in some way? At this point, a sizable number of studies have sought to shed light on this question, and the results are quite surprising.

In one recently published study, wepresented naive participants, academic researchers, and researchers who specifically work on happiness with different vignettes that described both an agent’s psychological states and the more general life that the agent was living. In all cases, these agents were always described as having extremely positive psychological states (feeling good, experiencing a lot of satisfaction, and rarely ever feeling bad). However, in some of the cases, the agents were described as living a life that we expected participants to see as normatively good (e.g., being kind to and caring for others), while in others, the agents were described as living a life that we expected participants to see as normatively bad (e.g., being cruel and harming others). We’ll refer to these as the ‘moral’ and ‘immoral’ agents.

After participants read about one of these two kinds of agents, we asked them a series of questions. First, just to make sure they accepted the key premises about the agent’s psychological states, we asked them whether the agent feels good, experiences general satisfaction, and does not feel bad. Fortunately, almost all participants agreed that the agent did have these states. Then came the real question: Is the agent happy?

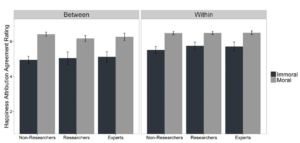

On this latter question, we found a surprising result. Even restricting to the participants who agreed that the agent had positive psychological states, participants who got the story about the immoral agent were less inclined to say that the agent was happy. Moreover, we found this pattern to hold regardless of whether the participants were naive subjects, academic researchers, or even experts working specifically on happiness. In fact, we even found this pattern to hold in both a between-subjects design (where each participant only reads about one agent) and in a within-subjects design (where participants read about pairs of immoral and moral agents who were explicitly described as having identical psychological states). As you can see below, this tendency is extremely robust.

A second important piece of evidence is that this effect seems to be pretty specific to the concept of happiness and does not extend to other assessments of how the agent feels. Consider one study that provides some nice evidence for this. Just as in the study described above, participants read brief vignettes that described both an agent’s psychological states, and the life that the agent was living. In this case, the agents were (1) either described as having highly positive or highly negative psychological states and (2) either described as living a life we thought participants would find to be normatively bad or normatively good. After reading about an agent, participants were asked one of two questions about that agent.

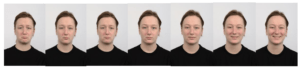

One question asked them about the feeling that the agent experiences. Participants selected one of seven different faces which had been created using facial morphing to make a scale that ranged from highly negative affect to highly positive affect (like the one below):

The other question simply asked them to indicate the extent to which they agreed that the agent was happy (on a seven-point agreement scale that ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree).

Participants’ judgments produced a pretty clear pattern: Assessments of the agent’s happiness were strongly affected by whether the agent was described as living a normatively good or normatively bad life, but in comparison, assessments of how this agent feels were not.

So what do these studies tell us about the ordinary concept of happiness? As far as the ordinary concept goes, is being happy simply a matter of having positive psychological states? The empirical evidence strongly suggests that the answer is no. Even when agents are described as having entirely positive psychological states, people show a reluctance to say that they are truly happy unless they also have morally acceptable lives. So then, should we go to the opposite extreme and say that the ordinary concept of happiness is just a matter of having a good life. Again, the answer appears to be no. Empirical studies on the ordinary concept have provided a wealth of evidence that assessments of happiness depend In a special way on the agent’s psychological states. In fact, changes in the agent’s psychological states tend to have a bigger impact on assessments of happiness than changes in the normative value of the agent’s life (you can see this in the above figure, for example).

In short, the current state of research on the ordinary concept of happiness doesn’t give us a straightforward answer to the question we started with. It’s clear that ordinary assessments of happiness depend both on psychological states and on normative value, but it’s not clear how these two factors are related or precisely what role they play in the ordinary concept. At this point, we suspect that what is needed is not just additional empirical studies but careful philosophical thought about what the existing data might be telling us.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Jonathan Phillips earned his Ph.D. in Philosophy and Psychology from Yale in 2015, and is currently at postdoctoral fellow in psychology at Harvard. Much of his work surrounds theory of mind, causal reasoning, moral judgment, formal semantics, and happiness.

Joshua Knobe is an experimental philosopher, appointed in both the Program in Cognitive Science and the Department of Philosophy at Yale University.

Really interesting stuff. You mention that this pattern remains robust even in a within-subjects design. (I actually think these are generally underused.) One question: you, Joshua (but perhaps Jonathan would also agree with this, I don’t know) have argued that the side effect effect is not some bias or blunder, but represents a legitimate and deep feature of our cognition (we are “moralizers through and through”). However, there is some evidence suggesting that the side effect effect asymmetry is also less pronounced when people get both versions of the story at the same time. Do you think this type of evidence is relevant to the legitimacy-question? And if so, what does it show?

Thanks for your interesting post. I have three interrelated questions for you, if I may.

First, is it thus the case that the subjects making the happiness judgments divide into two groups: those for whom happiness is a partly psychological, partly evaluative concept, and those for whom happiness is a purely psychological concept? Given the way the graphs look, I would assume that for some percentage of the subjects, their happiness judgments are not at all sensitive to whether the person being judged is moral or immoral (these would be the subjects with a purely psychological concept of happiness).

Second, if some percentage of subjects have a purely psychological concept of happiness, do you know how big this percentage is? 10%? 50%? I’d love to know that. And maybe it is already in the data.

Third, so long as this percentage isn’t tiny, should we conclude that there are in fact two ordinary concepts of happiness, one purely psychological and one partly evaluative? (If the percentage were tiny, then maybe a more plausible view would be that this tiny percentage of people who, in ordinary contexts, use ‘happy’ in a purely psychological way are just misusing the word.)

Thanks!

Hi Hanno,

Great point. The side-effect effect does emerge when each participant receives both versions, but just as you say, the effect becomes smaller in that kind of design. What exactly does this show?

In my view, it does not tell us anything directly about the cognitive processes underlying people’s ordinary intuitions. Rather, it shows that people themselves sometimes conclude, on reflection, that these intuitions involve an error.

In other words, people have some capacity for arriving at intuitive judgments (of intentional action, of happiness, etc.). There is then a debate among researchers about whether these intuitions involve an error. Presumably, the researchers are using some different kind of cognitive capacity to do their research from the one participants are using to answer the question. When participants are given both versions back to back, it is not as though their responses involve some new and different way of arriving at intuitive judgments that is cleansed of any errors. Instead, the participants are being placed in the same kind of position that researchers are. Just like the researchers, the participants can reflect on the pattern shown by their ordinary intuitions and ask themselves whether it looks like an error. In some cases, they may do precisely that, but this doesn’t reveal anything new about the ordinary capacity for intuitive judgments – it reveals something about people’s capacity for reflecting on those judgments in the way that researchers typically do.

Does that sound right to you? Definitely happy to discuss further, if you have a different take on this.

I have yet another question (not related to the ones I asked above). The results you describe suggest that some people’s happiness judgments are sensitive to whether the person being judged is moral or immoral. Are there studies about whether some people’s happiness judgments are sensitive to whether the person being judged is radically mistaken about their circumstances (as in, e.g., Shelly Kagan’s “deceived businessman” thought experiment or the experience machine case)?

(See https://books.google.com/books?id=JJVLDwAAQBAJ&lpg=PT475&dq=kagan normative ethics&pg=PT56#v=snippet&q=”imagine a man who dies contented”&f=false for Kagan’s case.)

I was afraid that link might break. You try here for Kagan’s case if you don’t know it: https://goo.gl/3Swddt

Hi Chris,

These are both great questions. Let me take the second one first, as I think it gets at something really fundamental about the ordinary concept of happiness.

In one study from Phillips and colleagues, participants were randomly assigned either to receive one of four kinds of cases:

1. agent believes she is helping others and really is helping others

2. agent believes she is harming others and really is harming others

3. agent believes she is helping others but is actually harming others

4. agent believes she is harming others but is actually helping others

What impacted happiness attributions was whether participants thought that the thing the agent believed she was doing was morally good or morally bad. By contrast, it didn’t matter what the agent actually was doing. In other words, participants thought the agent was truly happy in condition 3.

Ultimately, then, participants seem to be making a moral judgment, but it is a judgment about the agent’s mental states, rather than about what her life actually is like.

(The study itself is available at: https://philpapers.org/archive/PHITGI.pdf)

Hi Josh,

This is interesting stuff. Thanks for sharing!

I wonder if you think the results of the study on happiness that you describe here are related to your previous work on the deep self. I suppose my thought is that subjects might be thinking something like this: When people living immoral lives experience positive states, their affective responses are alien to their true selves. Really, deep down, they are opposed to their lives, yet, for whatever reason, their affective systems aren’t tracking what they are truly committed to. So, deep down they aren’t really happy, even though they experience positive feelings.

Do you find something like this at all plausible? I’d be really interested to hear your thoughts about any possible connections between these realists and your work on the deep self.

Hi Ben,

We are extremely uncertain about how to explain this effect, but the hypothesis you propose here is definitely a very plausible one.

Existing research shows that people tend to assume that everyone is drawn, deep down, toward a morally good way of life. Thus, when people see an agent living a morally bad life, they may be inclined to assume that there is still some part of this agent – perhaps one hidden deep down in her self – that condemns everything about the way she is leading her life. This may then lead them to conclude that she is not truly happy.

Though the jury is still out, we provide at least some evidence in favor of this hypothesis in the paper at: https://cpb-us-west-2-juc1ugur1qwqqqo4.stackpathdns.com/campuspress.yale.edu/dist/3/1454/files/2016/02/tsee-z6yimr.pdf

Hi Chris,

Thanks for these really excellent questions. I just went digging a bit through the data (only for the one study where we actually asked participants about both the moral and immoral version of the same agent).

As you suggested, there are definitely participants who don’t differentiate between the immoral and moral agents. The design of our experiment is such that it’ll give us a very conservative estimate estimate of the number of people who *do* differentiate (i.e., the experimental pragmatically biased against differentiating). Still, what we find across all group is that ~32% of participants differentiate between the happiness of the two agents (and so ~68% give them identical ratings). Interestingly, these percentages also don’t seem to change depending on academic training: ~30% of non researchers differentiate; ~30% of academic researchers differentiate; ~38% of happiness experts differentiate. (Note that this is also restricting to people who already said that both agents experienced positive emotions, were highly satisfied and did not feel negative emotions.)

The question about what to make of this (i.e., whether to conclude that participants are relying on multiple distinct concepts of happiness) is harder. One possibility is that there really are two totally distinct concepts that both happen to be connected to the English word ‘happy’. An alternative possibility is that there is actually only one underlying concept, but that it has a ‘dual-character’. That is, it’s a concept that characterizes its members both relative to a set of purely descriptive features and relative to a set of normative features (see http://experimental-philosophy.yale.edu/dual-character.pdf). In a series of studies that didn’t make it into the final version of the paper, we ended up finding a decent amount of empirical evidence that happiness is a dual-character concept. I’d be happy to tell you more about that (or send you a write of those studies) if you’re interested!

(I’ll respond to you other question separately.)

Jonathan, thank you for taking the time to look through the data. Those results are interesting. I’m not familiar with the difference between there being two concepts of happiness and there being one concept with a dual character. But I will check out your paper on dual-character concepts. Thanks.

I have yet another question (sorry to be so greedy). A sentence like ‘Bob is happy’ is, I believe, ambiguous between at least these two things: it might mean (a) that Bob right now feels happy or is experiencing happiness; or (b) it might be used to make a more global judgment, a judgment about overall happiness, usually over some period of time. Let’s call the first concept “occurrent happiness” and the second one “general happiness.”

Just to be sure that these two notions are clear, here are examples. Consider this remark: “I was so happy when they told me I got the job, but only for about a minute; that’s when it hit me that if l took it, I would have to leave you.” The speaker here is using ‘happy’ in the occurrent sense. And here is an example of a use of ‘happy’ in the general sense: “Look at you with your fancy job and car and house. But are you happy?”

My question is: when the subjects were asked to rate the happiness of the people in the examples, were they being asked to rate their occurrent happiness (at some given time) or their general happiness? Or might the question have been unclear such that some subjects may have thought they were being asked about occurrent happiness while other subjects thought they were being asked about general happiness?

My suspicion is that judgments of general happiness will be more sensitive to moral factors than judgments of occurrent happiness. Maybe occurrent happiness is in fact a purely psychological concept. I don’t suppose this has been tested, has it?

Hi Chris,

I think the way that we designed our studies definitely biases a “general happiness” reading. For example, the vignettes that we had participants read described the agent’s life in a very general way before asking them to assess the agent’s happiness.

I definitely share your intuition that the moral status of the agent’s life might matter less for questions that focus specifically on assessments of how happy the agent is right now, though I wonder if this will map cleanly onto two distinct concepts: one that is normative and one that is purely descriptive/psychological. My guess is that you’d still find an effect of morality even in assessments of “occurrent happiness”. Consider a person who is currently feeling delight and satisfaction at having succeeded in swindling money from an old and helpless person. Maybe we should just run the study, but I’d guess that people would judge that the person is less happy right then than a person who feels the same way because they just helped an old person. Definitely just an open empirical question though…

I actually vaguely remember some actual research on this, but I’m having trouble locating it. Give me a day or so to see if I can find it and I’ll get back to you! great

Hi Josh,

thanks a lot, that is a really important clarification I hadn’t thought about. The one question that remains for me is whether you think this issue has any bearing on the legitimacy issue. Everyone seems to think, on reflection, that the asymmetry should be smaller (or, as some studies suggest: non-existent). Does this provide (defeasible and inconclusive) evidence that the SEE is an error?

Cheers,

Hanno

Hi Jonathan. Interesting. Yeah, it could be we would still see an effect even for occurrent happiness. If you do dig up that research, please let me know!

Hi Josh and Jonathan,

Thanks for a fascinating article. In my book on well-being I claimed on the basis of experience and observation that many people think of “true happiness” as requiring moral goodness. So thanks for giving me some “hard” evidence for my claim! However, I’m puzzled by your finding that, like naive subjects, happiness experts also have a partly moralized conception of happiness, since you also say that the scientific definition of happiness is entirely non-moral. Did the social scientists just change their minds when they became participants in your studies? or were they already silent renegades?!

Many thanks

Hi Hanno,

That is a good point. Perhaps it would be helpful here to introduce an analogy. In epistemology, we often care a lot about people’s intuitions about individual cases, but it would also be possible to consider people’s intuitions about more theoretical questions regarding the relevance of particular factors. That is, in addition to looking at people’s intuitions about whether certain individual cases count as knowledge, we could look at people’s more theoretical intuitions about , e.g., the relevance of stakes, or about safety vs. sensitivity. I could imagine different philosophers having different opinions about the philosophical significance of this latter type of intuition. Some might say that we should only care about people’s intuitions about individual cases, while others might say that we should also care about people’s intuitions regarding these more theoretical questions.

In any case, my thought is that the pattern we observe when each participant receives both versions is reflective of this more theoretical type of intuition. What we are learning is that although people’s intuitions about intentional action in individual cases are influenced by moral considerations, people have an intuition at a more theoretical level that moral considerations are not relevant to the question as to whether a behavior was performed intentionally.

Hi Neera,

Great to know that this connects up so closely with your earlier work, and thanks so much for this question. To be honest, the answer is that I was extremely surprised by the result we obtained, and I still don’t know quite what to make of it.

Here is the key background. In a previous paper, we had explored the concept of innateness. There too, people’s ordinary intuitions are impacted by moral considerations, but scientists have developed a conceptual framework that doesn’t seem to involve morality. What we found was that moral considerations impacted scientists’ judgments made about individual cases but that scientists overrode this tendency when they have an opportunity to notice what they were doing. More specifically: scientists regarded a trait as more innate when they received the morally good case than when they received the morally bad case, but when they saw both cases back-to-back, they said that the two cases did not differ in innateness. (That paper is up at: https://cpb-us-west-2-juc1ugur1qwqqqo4.stackpathdns.com/campuspress.yale.edu/dist/3/1454/files/2016/02/Innateness-2hxvu8f.pdf)

When we tried the same thing with happiness, I expected to get the same result – but I was completely wrong. Instead, scientists were more inclined to attribute happiness in the morally good case than in the morally bad case, and they continued to show this difference even when they were given the two cases back-to-back. I could try speculating about what is going on here, but first I would love to hear your opinion. Do you have any ideas?

Hi again Chris,

I can’t seem to find the studies I thought I remembered hearing about, but I did find something that may be of interest. It’s some nice work that was done by Andy Vonasch (http://andyvonasch.wixsite.com/mysite). He asked participants two different questions: sometimes they were asked whether the immoral/moral agents ‘feel happy’ and other times he asked whether they had ‘true happiness’. He found basically two effects. The first was that morality had a much much bigger effect on responses to the question about ‘true happiness’. The second was that morality still had a noticeable, even if much smaller, effect on responses to the question about whether the agent ‘feels happy’.

I’d definitely be interested to hear what you think about this finding. (The work isn’t published, but I could ask Andy if I could send along a write-up of the studies if you’re interested.)

Thanks for this intriguing work! It occurs to me that it might be worth testing different conceptions of happiness for this effect – e.g. using the Cantril Ladder questions about life satisfaction as well as questions about affect – though perhaps this was already suggested by the comments above: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK189562/ I also expect you will find similar results for other things that contribute to “quality of life” besides moral value e.g., you might ask people: Is someone who achieves a lot vs a little happy etc.? In any case, thanks again for writing this!

Hi Nicole!

A huge thank you for creating this whole series, and also for your very interesting comment. This is really a great question.

Nina Strohminger recently ran a study to address precisely this question, and she found a surprising result. The really does seem to be something about *morality* in particular that people find relevant for happiness.

For example, suppose that an agent lives a deeply immoral life, but despite this, she feels very good all the time. In that kind of case, people tend to say that she is not truly happy.

By contrast, suppose that an agent abandons her dreams of becoming an artist (or doesn’t have any close friends, or never accomplishes anything of value) but still manages to feel good all the time. In those other kinds of cases, people actually *do* say that she is happy.

In other words, for reasons we do not completely understand, this effect seems to arise only for moral judgments and not for any other kind of judgment about the goodness or badness of a person’s life.

Jonathan,

That study that you mention by Andy Vonasch is very much in the ballpark of the sort of study I was wondering about. So thanks. I’m not surprised by his finding that judgments of ‘true happiness’ are sensitive to moral factors. But I am pretty surprised that judgments of ‘feels happy’ are even a little bit sensitive to moral factors.

Suppose the percentage of people who apply the term ‘feels happy’ in this moralized way is small — say, below 5%. Do you think it would be plausible to say that these people are just misusing the term, that they fail to understand what the term ‘feels happy’ means?

Chris

Thanks again!

Thanks for your answer, Josh. I’ve just returned from a conference, so I haven’t had time to read the article on innateness that you linked to. I confess, though, that I don’t see the parallel between the innateness study and the happiness study. Intuitively, I would expect people (even scientists) to say that if a trait is innate in a case of moral badness, then it’s innate in a case of moral goodness, and to be more inclined to attribute happiness to a morally good person than a morally bad person. What surprised me was that scientists forgot their scientific definition of happiness during the studies! The abstract of the paper on innateness states that scientists were more likely to use their scientific concept of innateness when the task encouraged them to think in terms of general principles, and the ordinary concept when the task encouraged them to think in terms of specific cases. This is very interesting! Have you done studies of happiness using these two kinds of conditions with scientists to see if you get the same result? Thanks again for your response.

Hi Neera,

Thanks so much for getting back to us about this! I’m really impressed that you even went so far as to take a look at our other paper – I definitely wouldn’t have expected that – and I really appreciate these further comments.

Basically, the two papers use exactly the same method. In both, we find that people’s ordinary intuitions are impacted by value judgments in a way that seems to depart from what scientists would do if they just straightforwardly followed their explicit theories. In both, we then ran the experiment on scientists. In both, scientists were randomly assigned to receive the question in one of two formats.

(1) Some scientists were assigned to receive just the morally good case or just the morally bad case – which one might think would lead them to rely more on their intuitions.

(2) Other scientists received both versions back-to-back – which one might think would lead them to rely more on explicit theoretical reasoning.

In the case of judgments about innateness, scientists showed an effect of moral judgment when the materials were presented in format (1), but the effect was almost completely eliminated when they received the materials in format (2). this indicates that scientists rejected their intuitive judgments when they had a chance to use a process of more explicit theoretical reasoning.

I predicted that the same thing would happen for judgments of happiness, but that’s not what happened at all. Instead, scientists showed an impact of moral judgment both when the materials were presented in format (1) and when they were presented in format (2). In other words, to our great surprise, scientists continued to show the effect even when we made it completely obvious what they were doing.

Thanks Josh. (I wonder why I your response didn’t come through to my email inbox.)

I see that I misunderstood what you were comparing in the two sets of experiments. Sounds like scientists don’t really believe their own scientific conception of happiness! Do you know how many of them thought that moral goodness contributes to happiness, and how many didn’t?

Hi Neera,

Great question. Overall, we found that 38% of happiness researchers attributed less happiness in the morally bad case than in the morally good case when the two cases were presented back to back. We found this very surprising, since more explicit theoretical discussions of the nature of happiness almost always emphasize psychological states (feeling good, not feeling bad, feeling satisfied with one’s life) rather than anything involving moral value.

And as I recall, you said that there was no difference between the happiness researchers and other participants. But can you tell me how many people overall, and how many happiness researchers, participated?

Absolutely. We had 294 non-expert participants and 299 psychology researchers. Of the psychology researchers, 129 indicated that they had done research on happiness specifically

Thanks again!