Most contemporary work on well-being assumes that individuals have several different kinds of well-being:

- Momentary well-being—i.e., well-being at a particular point in time.

- Periodic well-being—i.e., well-being during some extended period longer than a moment but shorter than a whole life (say, a day, a week, a year, or a chapter of a life).

- Lifetime well-being—i.e., the well-being of one’s life considered as a whole.

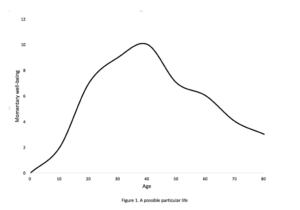

Many philosophers of well-being, not to mention welfare economists, use a particular sort of graph to depict a person’s life (Figure 1).

Here, time or the person’s age is represented on the x-axis and momentary well-being is represented on the y-axis.

Let us group momentary and periodic well-being together and call them temporal well-being.

Two central topics in the philosophy of well-being are: (1) the nature of temporal well-being (i.e., what determines well-being at a moment and during a period), and (2) the relationship of temporal well-being to lifetime well-being (additivists, for example, hold that lifetime well-being is equivalent to the sum of momentary well-being throughout one’s life—i.e., the area under the curve in the above sort of graph).

In The Passing of Temporal Well-Being, I argue that all this literature is premised on a giant mistake, for there is no such thing as temporal well-being. The only genuine kind of well-being is lifetime well-being. I give two arguments for this claim. Here, I will mention only the first, The Normative Significance Argument. It goes like this:

- Genuine well-being is intrinsically normatively significant (i.e., can make an intrinsic difference to the value of outcomes, and provide us with, or be the ultimate source of, reasons for action (self-interested or agent-neutral)).

- Only lifetime well-being (among putative kinds of well-being) is intrinsically normative significant.

Therefore,

- Only lifetime well-being is genuine well-being.

Why is there no temporal well-being? It is because if temporal well-being were to exist, it could not have the sort of normative significance it would need to have in order to count as a genuine kind of well-being. Temporal well-being, then, is an oxymoron. It is the idea of something that, since it is well-being, has intrinsic normative significance, but since it not lifetime well-being, cannot have this sort of significance. What I am advancing is, in effect, an ‘error theory’ about temporal well-being.

(2) is the more controversial premise, so I will focus here on it. What is my argument for (2)? In the book, I give seven arguments for it (and respond to six objections to it). I will mention just one of these arguments here.

It is common to debate the fortunateness of particular individuals in history. Was Gandhi a fortunate person? How fortunate, on balance, was Marilyn Monroe? What about John Lennon? And so on. Who were the most fortunate individuals in history? Who were the least? In carrying on these debates, we do not form evaluations of these people’s lives considered as wholes, and then add to these estimations of the value of various times or periods within these people’s lives, in order to arrive at assessments of their “overall” levels of fortunateness. Rather, we are interested here ultimately just in the value for these people of their lives considered as wholes.

To be sure, we are, on such occasions, interested in what happens at or during particular times or periods in these people’s lives. We might even speak of their faring well or poorly at or during certain times or periods. But here we seem interested in these things just for their implications for these people’s ultimate levels of lifetime well-being.

A person’s fortunateness, in other words, does not seem equivalent to her lifetime well-being plus her childhood well-being plus her adolescent well-being, and so on. Overall fortunateness, at least as we are interested in it in thinking about the lives of historical figures, seems equivalent just to lifetime well-being. To be interested in how fortunate John Lennon was is to be interested just in the well-being of his life considered as a whole (including, perhaps, all of the various respects in which, considered as a whole, it went well or poorly for him).

Suppose this is right, and there is no such thing as temporal well-being. What, then, are we doing when we say things like “Things are going well for me right now”, “I had a good day today”, “How is Bill doing these days?”, “Ellen had a blessed childhood”, and so on? How can we account for such talk if there is no such thing as temporal well-being? Am I suggesting that at all these times we are talking nonsense?

Such talk, I believe, should not be interpreted literally, but calls for a subtler analysis. One thing, for example, we are often doing when we say things like “Ellen had a blessed childhood” is commenting on the intrinsic contributions of the events and experiences of the relevant period to a person’s lifetime well-being. So, for example, if I say that I had a great time during college, or that my college years were the best of my life, I might be saying that there were certain events or experiences then (for example, romantic encounters, discoveries of great music, travels or adventures with friends, intellectual stimulation, and so on) that will, at the end of the day, have been among the greatest intrinsic contributors to my lifetime well-being.

Suppose I’m right that there is no such thing as temporal well-being. What follows? One thing that follows is that philosophers are wasting a great deal of time theorizing about its nature. Their efforts are doomed to failure, since there is nothing here to give a theory of. Moreover, many are wasting their time trying to work out how lifetime well-being is constructed out of temporal well-being. Lifetime well-being cannot be constructed out of temporal well-being, since there is no such thing as temporal well-being. To take just one example, an Uphill Life cannot be better for one, other things equal, than a Downhill Life. The question of whether it is, is simply ill-conceived. Lives don’t have shapes or directions, at least not shapes or directions of something like momentary well-being. Similarly, debates about temporal neutrality—i.e., about whether temporal benefits later in life add more to lifetime well-being than temporal benefits earlier in life do—are empty. Philosophers are also wasting their time trying to solve the timing problem for the badness of death. It is a pseudo-problem. There is no problem of how death can harm us without making us worse off at some time, since there is no such thing as well-being at a time. Nothing can make us worse off at a time. We do not have well-being at times for death to potentially reduce. Likewise, the sort of graph mentioned above should be done away with. We cannot map well-being in this way. For this reason, my thesis has major implications for public policy, which often refers explicitly to the effects of different policies on momentary well-being.

Am I proposing we stop talking and asking about how people are faring at times and during periods such as childhood? No. There is no harm in continuing to talk this way, provided we do not allow ourselves to be misled by the surface grammar of such talk into thinking that we are here attributing to people a state that they can be in at times that has normative significance independently of its implications for lifetime well-being.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Ben Bramble is a professor of philosophy at Trinity College Dublin. He works mainly in moral and political philosophy. He has published on a diverse range of topics, including pleasure and pain, well-being, meaning in life, value theory, William James, desire and motivation, animal ethics, and medical ethics. To learn more about his forethcoming book, Passing of Temporal Well-Being, vist (http://www.benbramble.com/passing-of-temporal-well-being.html)

Hi Ben,

Perhaps you respond to something like this in the book. But here is one reason to think that you are mistaken about premise 2, inspired by the work of Dennis McKerlie. We can predict that a person, A, is going to have a pretty nice life in the absence of our intervention. That nice life is made up of seven decades of (what most people would call) very high momentary well-being, and one decade of (what most people would call) terrible well-being, which comes at the end.

Another person, B, is going to have a pretty nice life as well, but not quite as nice as A’s. B’s nice life consists of eight decades of uniformly high well-being, but not quite as high as A’s first seven decades.

Say we can intervene at the start of the eighth and final decade, and improve only one of A’s or B’s well-being. We should improve A’s well-being, because otherwise she will have a terrible time. But a lifetime view cannot explain this, since A’s lifetime well-being is higher than B’s.

That isn’t to say that there are no cases where lifetime well-being matters more than future periodic well-being. If B’s life had been pretty terrible too, but just a little better than A’s worst period, I’d be inclined to say we should help B. That, to my mind, suggests that both lifetime and momentary well-being count. But at the very least, I’m curious how you respond to the initial case.

Thanks for a very interesting post.

Nice post Ben! Might it be possible to derive measures of momentary well-being from lifetime well-being by comparing counterfactual ways one’s life can go? Assume Jon Lennon had x lifetime well-being. If we want to know how much the success of “(Just Like) Starting Over” (the last single of his released in his lifetime) contributed to his lifetime well-being, we just compare Jon Lennon to his counterpart who, say, was killed two months earlier, so before the song’s release. Let’s assume that this Jon Lennon* had x-n lifetime well-being. Can’t we then say that the success of his last single contributed n periodic well-being to Jon Lennon’s life? If you can say this, then you can derive the periodic well-being of any segment of someone’s life by comparing the right counterfactuals. The periodic well-being during any segment of someone’s life is just the difference in lifetime well-being between the persons counterpart who dies right before the segment and the counterpart who dies after it. This is an admittedly grim way of thinking about periodic well-being, but maybe there’s something to it.

Hi Ben,

Thanks for your comment!

Is your worry that my view has a counterintuitive consequence, namely, that we should improve B’s final stage, rather than A’s? Why do you think it has this consequence? My view here, after all, is one just about well-being, and so, strictly speaking, doesn’t entail anything about what we should do. But let’s just suppose, as I think you may be suggesting, that my view implies (or else that I would want to accept anyway) that we should do what would maximize lifetime well-being. (For what it’s worth, I do accept this.) Now, in the case at hand, why am I committed to saying that we should improve B’s final stage, rather than A’s? I don’t get this. On my view, whether we should improve A’s final stage rather than B’s depends just on the contributions these final stages would make (in virtue of their events and experiences, and perhaps also their relationships to other life stages) to these individual’s lifetime well-being. Why think that making B’s final stage a little better would add more to B’s lifetime well-being than making A’s final stage much better would add to A’s lifetime well-being?

Perhaps your point is that there might be cases where we have to choose between (i) what would give someone the best future, and (ii) what would give them the best life considered as a whole, and that in such cases (i) is sometimes the better choice. If so, this is a worry also made by Ben Bradley, and one I respond to in section 2.3 of the book (in the subsection “the best future”).

Ben

Hi Phil, thanks for your comment!

That’s an interesting suggestion. I’d be more tempted to say that a person’s well-being at a certain time is determined by the difference in lifetime well-being of their actual self and that of their counterpart who didn’t have this time. (What do you think of this suggestion?)

I’m more tempted still to say that it is just *the contribution of a time to a person’s lifetime well-being* that is determined in this way. I don’t see what is gained in talking about well-being at a time once we already know of the contributions of times to lifetime well-being.

Ben

Ben,

This may be more of a clarificatory question than an objection as such. We often talk of life’s ‘ups and downs’. And when we look back on the life of people, say, Eric Clapton, we note his successes (Bluesbreakers, Cream) and failures (Solo stuff) and the tragedies (the death of his son, addictions, broken relationships). How does the concept of lifetime well-being cohere with this way of thinking about a persons’ life. Ups and downs are temporally focused – they don’t make sense as judgements about lifetime wellbeing.

Hi John, good question! Thanks for commenting. I agree, of course, that there are successes and failures (and tragedies) in life, and, in a certain sense, ups and downs. But I don’t think we need the concept of temporal well-being to make sense of these things. Clapton’s failures and tragedies were certainly bad for him, but they were bad for him, not by making him worse off in the moment or at the time, but just by directly reducing his lifetime well-being (or else by causing things–say, pains–that themselves directly reduced his lifetime well-being). Were things going poorly for Clapton during his periods of addiction/relationship-breakups, etc.? Strictly speaking, no, since there is no such thing as temporal well-being. But it is certainly true that at these times a lot of stuff was happening that, at the end of the day, will greatly reduce Clapton’s lifetime well-being. In this sense, and only in this sense, were these bad times for Clapton. Is that helpful?

Ben

Ben,

Thank you for the post.

I have a scenario that I was hoping you could respond to.

Scenario 1) Suppose I am deliberating over whether to step on someone’s toes. I know that doing so will cause them a brief amount of pain. but I also know that stepping on this person’s toes will delay them from walking into the street and getting run over by a bus. (Assume that stepping on this person’s toes is the only way to save them from getting hit by the bus.) Intuitively, even though the *balance* of reasons is in favor of stepping on this person’s toes, that balance *includes,* on one of its scales, a reason against stepping on this person’s toes (since, in general, there is always a outweigh-able reason against causing pain). Don’t these facts speak in favor of temporal wellbeing being a source of contributory reasons?

Avi

My question is similar to Avi’s. (Actually, it might be the same question…)

Your premise 2: Only lifetime well-being is intrinsically normatively significant.

Consider this case. In a high-school hallway, a jock in a bad mood knocks the books out of the hand of a smaller boy and scatters them.

The jock’s action is wrong because it is callous/cruel/mean, right? But it seems unlikely that his action makes any contribution to the victim’s lifetime well-being. (It will probably be soon forgotten.) If it DOES make a contribution to lifetime well-being, it’s hard to predict what that contribution will be. (Some day it might be a funny story, or a growing experience, or it might be a continuing source of humiliation. Who knows.)

So I want to cache out the wrongness of the hallway violence in terms of well-being, but it’s only momentary well-being that could do that. It’s cruel to knock the books out of a student’s hands because that causes him pointless pain and frustration in the moment.

On the flipside: reasons of kindness and reasons of prudence are grounded in some concept of well-being. If we see a way to promote the lifetime well-being of someone else our ourselves, that certainly yields a reason. But kindness and prudence still exist in situations in which we know we have no clue how to judge effects for lifetime well-being.

In fact, in the case of infants and young children, reasons of kindness still exist in small-scale, low-stakes circumstances where we KNOW that kindness won’t have any consequences for life-time well-being. Put the colorful band-aid on the scratch that doesn’t warrant it because it’s the kind thing to do– which is to say it makes the child calm and happy right now, even though we know the kid will be on to something else in 15 minutes, no matter what we do.

Why doesn’t this suggest the existence of momentary well-being?

Hi Avi, thanks for your question. In stepping on the person’s toes, you make them worse off in their life considered as a whole *in one respect*, for you make it the case that they had one additional toe pain in their life. *This* is your pro tanto reason to not step on their toe (even though doing so saves their life). (To be honest, I’m actually not sure whether pains like that really do reduce lifetime well-being in any respect, since many such pains are *purely repeated*–i.e., add nothing qualitatively new in terms of painfulness to a person’s life. But that is a whole other story.)

Best,

Ben

Hi Ian, thanks for the comment. The trauma of being knocked down reduces the kid’s lifetime well-being in one respect. It makes it the case that her life as a whole included one episode of such trauma when it otherwise wouldn’t. This is true, even if she forgets about it. It is true even if it was on balance best for her, by helping her to learn/grow/develop character, or by giving her a laugh later on in life, or whatever. Why was it *morally wrong* for the bully to knock her down? That’s a separate matter, and I’d want to appeal to the intentions of the bully to explain it. On my view, it might have been morally wrong to do so, even if it happened not to traumatise the student at all and so reduce her lifetime well-being in *any* respect. As for reasons, I deny that whether an action is morally right or wrong is itself a source of reasons. Only well-being (one’s own or others’) is.

Best,

Ben