Singer Without Utilitarianism: On Ecumenicalism and Esotericism in Practical Ethics

Johann Frick (jfrick@berkeley.edu)

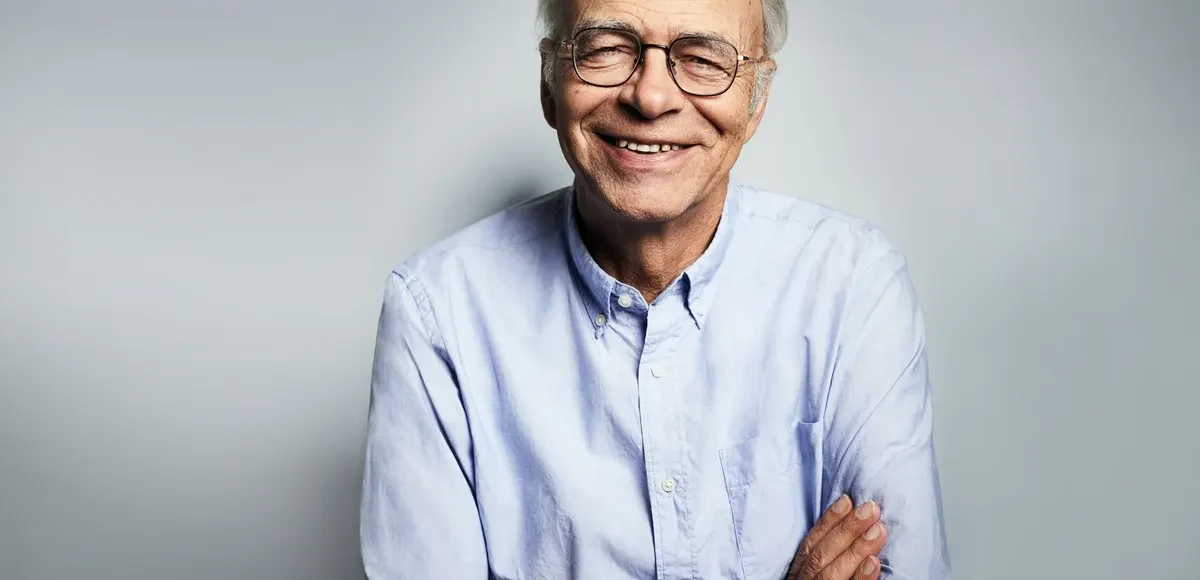

The following is a short talk that I delivered at the Peter Singer Farewell Conference at Princeton University, May 13-14, 2024. It’s part tribute to Peter, part reflection on his distinctive methodology in practical ethics. I thought that the themes it raises could be of interest to readers of the PEA Soup blog. Peter has told me that he plans to participate in our discussion, making this also an opportunity for another collective celebration of his amazing life in philosophy.

A heads-up: Since I am based in California, I may begin responding to comments with some hours’ delay

—

It’s a tremendous honor and a pleasure to open this celebration of my treasured former colleague Peter Singer.

Peter is the greatest utilitarian philosopher since Henry Sidgwick; so it is only fitting that this conference should begin with a panel devoted to utilitarianism.

What is more surprising, perhaps, is that the task of opening this discussion should fall to me, an avowed non-consequentialist. Reflecting on this irony led me to the subject of my talk: “Singer Without Utilitarianism”.

I am very far from being a utilitarian, yet I find myself in substantial sympathy with Peter on many positions he’s staked out in practical ethics – for example, regarding our duties to help the global poor or the moral significance of animal suffering – as well as on the arguments he marshals in their support.

This, I submit, is no accident: Many of Peter’s most influential contributions to practical ethics don’t require his readers to be utilitarians, or even consequentialists, to find them deeply plausible, even irresistible.

I want to reflect on two ways in which Peter has tried to make his arguments, and the ethical demands that he has publicly advocated for, as broadly appealing as possible, even to a non-utilitarian audience.

Doing so, I hope, will reveal some interesting points about philosophical methodology and the division of intellectual labor between practical ethics and other branches of philosophy. It will also allow me to put to Peter a question that I’ve always wanted to ask him, about a tension between the roles of philosopher and public campaigner.

- Ecumenicalism

The first of my two themes is Peter’s steadfast commitment to a form of philosophical ecumenicalism.

Peter has been an avowed utilitarian for most of his career, and his commitment to utilitarianism no doubt played a major role in leading him to adopt many of the ethical stances for which he is known.[1]

And yet, it is rare that you will find Peter, in his published work, making arguments of the form: “You should believe p, because p is entailed by utilitarianism, and utilitarianism is true”.

Much more commonly, you will find him skillfully appealing to mid-level principles that he expects will command the assent of people with widely divergent ethical outlooks. This genius for making his arguments as ‘ecumenical’ as possible is one of the major reasons for Peter’s success as a public intellectual.

There are countless illustrations that I could give you of Peter’s commitment to philosophical ecumenicalism. But let’s focus on perhaps the most prominent example: the argument of his celebrated article “Famine, Affluence, and Morality”.

As you all know, Peter’s case for a moral requirement to give to charity does not proceed from act-utilitarian premises. Rather, the central normative principle that underpins his argument runs as follows:

If it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought, morally, to do it. [2]

“Without sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance”, Peter goes on to explain, means “without causing anything else comparably bad to happen, or doing something that is wrong in itself, or failing to promote some moral good, comparable in significance to the bad thing that we can prevent.”[3] Let’s dub this “Singer’s Principle”.

Singer’s Principle, you will note, is logically much weaker than act-utilitarianism.

Anyone who accepts act-utilitarianism is committed to Singer’s Principle as well: Act-utilitarianism tells us to always act to maximize the good. In a situation where it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, preventing that bad thing is what maximizes the good. So act-utilitarianism entails the truth of Singer’s Principle.

By contrast, we can accept Singer’s Principle without accepting act-utilitarianism. For instance, Singer’s Principle expressly allows that an action, despite producing the best consequences, could be ‘wrong in itself’ – perhaps because it violates some right or deontological side-constraint. It also allows that an optimific action might not be morally required, because the sacrifice demanded of the agent would be too great.

The fact that Peter builds his argument, not on the controversial doctrine of act-utilitarianism, but on a principle that strikes many as far harder to deny, has made it a spectacular success. “Famine, Affluence, and Morality” almost single-handedly put global poverty on the map as a serious topic for contemporary moral philosophy and is frequently voted the “most convincing” philosophy paper of the 20th century. Even a died-in-the-wool non-consequentialist like T.M. Scanlon writes in his article “Contractualism and Utilitarianism” (the purpose of which is precisely to lay the foundations of a systematic alternative to utilitarianism) that he feels convinced by Singer’s argument and “crushed by the recognition of what seems a clear moral requirement.”[4]

There’s a general methodological lesson here that many of us try to drill into our undergraduates from their first semester: Philosophical writing aims at a form of rational suasion by means of reasoned argument. However, to be dialectically effective, a philosophical argument must pick people up where they are. Hence the advice that many of us impart to our students: ‘To make your paper as persuasive as possible to the widest possible audience, it is best, all else equal, to base your arguments on premises that are as widely shared and as uncontroversial as possible.’

But are there occasions when all else is not equal? Might there sometimes be a philosophical price to pay for this kind of ecumenicalism?

While persuasiveness may be a cardinal virtue of philosophical argumentation, what many of us are ultimately after in doing philosophy is a form of understanding. We want to understand, at the deepest and most fundamental level, the nature of reality, the knowledge we can have of it, and the principles and values that should guide our actions. This quest for understanding will often require us to venture beyond views that are widely held, and may lead us to conclusions that do not readily command consensus.

It is here that a possible trade-off emerges between the objectives of writing a paper that garners broad assent and one that achieves understanding of the most fundamental kind.

Singer’s Principle strikes many as extremely plausible, to the point of appearing almost self-evident.[5] At the same time, however, it seems like a paradigmatic ‘mid-level’ principle. Ultimately, we think, the truth of Singer’s Principle must be grounded in some more fundamental principle – such as act-utilitarianism or, alternatively, some non-utilitarian principle of beneficence – of which it is a corollary.

By remaining silent, in the text of “Famine, Affluence, and Morality”, about which more fundamental principle he thinks grounds our duties of aid, Peter maximizes the breadth of his article’s appeal. But the philosophical ‘price’ to be paid is that the philosophical explanation stops short of going “all the way down”.

Now, the obvious response on Peter’s behalf is that he has a deeper explanation ready to hand, even if it’s not to be found in the text of the article: Anyone who knows Peter knows that he thinks Singer’s Principle is true because act-utilitarianism is true.

Still, one might retort, leaving the question of what ultimately grounds Singer’s Principle out of the article, comes with a further theoretical cost: it significantly narrows the scope of the discussion, leaving us without guidance on some of the more vexing problems of beneficence. All else equal, we want a view that tells us what to do, not just in a relatively narrow set of circumstances, but in general. But this will be hard to do while remaining ecumenical — for a general view will have to deal with the controversial cases as well, where consensus is much harder to achieve.

It may not matter in Singer’s Pond Case whether the true theory of beneficence is act-utilitarianism or some non-consequentialist alternative that allows for agent-centered prerogatives and moral side-constraints. Singer’s Principle by itself is quite sufficient to tell us how to act.

By contrast, differences in one’s underlying theory of beneficence do begin to matter in more controversial cases – say, a case where you could prevent something bad from happening, but only by inflicting harm on an innocent bystander, or by making some very great sacrifice yourself. What to do in such situations falls outside the remit of Singer’s Principle. If the answer is supposed to be “just do whatever maximizes utility” then that is a much more controversial position, and one that would deserve serious philosophical scrutiny.

I hope I’ve said enough to persuade you that in doing philosophy there are sometimes tradeoffs between explanatory depth and generality, on the one hand, and the breadth of appeal that comes from an ecumenical approach, on the other.

What’s the right balance to strike between these competing values? I can’t defend a fully general answer on this occasion. But let me make a few observations.

It seems to me that the right balance may differ depending on what the stakes of our inquiry are.

A lot of even very good philosophy consists in motivating views that are, in themselves, not all that surprising or revolutionary. As Gideon Rosen puts it, the value of great philosophy often doesn’t lie in the ‘punch line’.[6] It will hardly come as a shocking revelation to hear a philosopher argue that, yes, persons do persist across time, and yes, discrimination is often wrong and to be avoided. The interest of philosophical work of this kind lies in the detailed and systematic account that it provides of the phenomena under discussion, and in the depth of understanding that this makes possible. Given that this is where the philosophical action is in such cases, explanatory depth and breadth are often rightly prioritized over consensus-building.

The aims of practical ethics, however, are quite different. Practical ethics, as the ‘activist wing’ of moral philosophy, aims at producing real-world effects by persuading people of some concrete moral proposition and rousing them to action. As such, a more ecumenical approach will often be appropriate – especially so when the view being argued for is non-obvious and practically consequential.

On both these counts, “Famine, Affluence, and Morality” was off the charts: When it was published, Peter’s argument about our moral obligation to help distant strangers in need was highly revisionary of common-sense moral thought, which (some religious traditions aside) tended to view charitable giving as praiseworthy but morally optional. And the real-world impact of Peter’s paper has been enormous: by revolutionizing our thinking about global poverty, it quite literally changed the world.

So, while there may be no one-size-fits all answer to how to balance philosophical ecumenicalism with explanatory depth and generality when doing philosophy, there can be little doubt that in “Famine, Affluence, and Morality” and in many of his other works in practical ethics, Peter got the balance spot on.

- Esotericism

Let me now turn to the second theme of my remarks. While I’ve just made the case that Peter’s philosophical arguments invoke utilitarianism less frequently and explicitly than one might have expected, I’m struck that Peter’s reasoning tends to be much more explicitly utilitarian when it comes to what positions publicly to promote. Ironically, approaching this question in a utilitarian spirit often leads Peter to moderate the content of his public exhortations.

Consider, again, the example of our duties of aid. It is notable that Peter’s writings on charitable giving have gotten significantly less demanding over time. “Famine, Affluence, and Morality” (1972) suggested that we ought to give until, if we gave more, “we would be sacrificing something nearly as important as the bad things our donations can prevent.” By contrast, the ‘new standard for giving’ that Peter promotes in the final chapter of his 2009 book The Life You Can Save asks me to donate only about 5.1% of my pre-tax annual income to charity.[7]

This scaling-back in Peter’s public demands is not due to a shift in his underlying convictions about how much I truly ought to give. Rather, it is the result of a calculation about what public message will have the optimal effect on people’s charitable giving in the aggregate. As Peter writes:

Asking people to give more than almost anyone else gives risks turning them off. It might cause some to question the point of striving to live an ethical life at all. Daunted by what it takes to do the right thing, they may ask themselves why they are bothering to try. To avoid that danger, we should advocate a level of giving that will lead to the greatest possible positive response. If we want to see those in poverty receive as much of the aid they need as possible, we should advocate the level of giving that will raise the largest possible total, and so have the best consequences.[8]

If Peter is right, we confront an interesting further trade-off: between speaking the (full) philosophical truth and changing the world for the best.

By seeking to publicly downplay the radical implications of his own ethical view, Peter is self-consciously engaged in what his great utilitarian forebear Henry Sidgwick calls “esoteric morality”. As Sidgwick writes in The Methods of Ethics:

on Utilitarian principles (…) it may be right to teach openly to one set of persons what it would be wrong to teach to others [or to do oneself in private].[9]

In “Secrecy in Consequentialism: A Defence of Esoteric Morality”, Peter Singer and Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek further expand on this thought:

It would not be right to advocate openly that people ought to give everything they can spare to the poor, because that would be counterproductive. The right level of giving to advocate openly is [say] 10%. On the other hand, assuming that I have no other relevant obligations that constrain me from giving more than 10%, I ought to give more, and in not giving more, I am doing something wrong. What if someone asks me, privately, how much she should give? If I know her well, and know that she is one of those rare people who would respond positively to a highly demanding standard, I should privately tell her what, as a consequentialist, I believe: that she ought to give substantially more than 10%.[10]

As you are all aware, the esoteric project in ethics – from Plato’s “noble lie” to Sidgwick and Singer – has been met with various objections: that it is inherently deceptive; manipulative; elitist; undemocratic; essentially parasitic on norms of good-faith communication; that it undermines open debate about morality; that it lends itself to abuse by self-interested elites; and that, even if engaged in in good faith, it is risky, since, were the (full) truth about the speaker’s actual views to become public, this might fatally undermine the credibility of his public message.

I share many of these worries about esoteric morality, but I will not attempt to litigate the issue here.[11] Instead, let me close by briefly arguing for three provocative theses, which do not depend on any particular view about the ethics of esotericism. Together, they bring out why it seems extraordinarily difficult to engage in what I shall call ‘esoteric campaigning’ while at the same time continuing to operate as a philosopher. I will then ask Peter to reveal how he pulls off this astonishing double-act.

1. Esoteric campaigning is not philosophy

An ‘esoteric campaigner’, as I will use the term, is someone who publicly promotes a moral code that is false or at least misleading by his own lights (for instance since it is too undemanding) because this is what he expects will have the best effect on the world. By that definition, Peter’s advocacy for his ‘new standard of giving’ is a form of esoteric campaigning.[12]

Being an esoteric campaigner may be honorable and even praiseworthy. But it is not, I submit, doing philosophy. Whatever else philosophy is, it consists in a good-faith pursuit of the truth, often in dialogue with other such truth-seekers. As Dan Brock puts it:

Truth is the central virtue of [philosophical] work. [Philosophers] are taught to follow arguments and evidence where they lead without regard for the social consequences of doing so. Whether the results are unpopular or in conflict with conventional or authoritative views, determining the truth to the best of one’s abilities is the goal.[13]

That philosophers aim to speak the truth, regardless of consequences, is precisely what is thought to set us apart from politicians, defense attorneys, motivational speakers, and Frankfurtian bullshitters.

So, when you speak as an esoteric campaigner, when you put out a message not because you believe it to be true but in order to have an optimal effect on people’s behavior, you are not really engaged in the activity known as philosophy.[14]

But not only is esoteric campaigning not philosophy. Wanting to operate as an effective esoteric campaigner tends to crowd out the space for doing philosophy (at least publicly). This is so because of a second truth about esoteric campaigning.

2. Speaking ‘as a philosopher’ risks undermining your work as esoteric campaigner.

If the assumption that motivates the turn to esoteric campaigning is in fact correct – namely that the public will be put off by hearing the (full) truth about what morality demands – then continuing to also speak openly as a philosopher is tricky. By assumption, it risks undermining your efforts as an esoteric campaigner.

The third thesis is a corollary of this:

3. Esoteric campaigners must wear a mask.

As Sidgwick noted,

it seems expedient that the doctrine that esoteric morality is expedient should itself be kept esoteric.[15]

In other words: The first rule of esoteric morality is “you do not talk about esoteric morality”. Whatever special epistemic authority philosophers may enjoy in the eyes of the public is predicated on the assumption that they are speaking as unbiased truth-seekers, who moreover have thought particularly deep and hard about the issues. Few people will willingly let themselves be influenced by someone who doesn’t himself believe what he is saying. To operate effectively as esoteric campaigner thus requires wearing the mask of the truth-teller.

What I find in equal measure puzzling and utterly endearing about Peter’s later work is that he seems to entirely ignore these maxims of esoteric campaigning. Thus, in his 2009 bestseller The Life You Can Save, Peter spends the first nine chapters of the book mounting a vigorous philosophical case in support of his old, demanding views on the ethics of giving. Then, in the tenth chapter, he abruptly changes tack and declares, with disarming openness, that he worries that most people will find Singer’s Principle offputtingly demanding; so it would be better to advocate for a more moderate standard of giving. Which he then proceeds to do.

I certainly admire the intellectual honesty. But, judged by the lights of esoteric campaigning, I find Peter’s openness about what he’s up to rather baffling. It’s a bit like telling his readers: “I’m worried that you can’t handle the truth. So I am now going to tell you a story that you’ll find easier to stomach.” The candidness seems self-defeating. It’s as if Peter, the philosopher, can’t quite bring himself to wear the mask that esoteric campaigning à la Sidgwick would seem to require.

And yet: It cannot be denied that Peter’s public advocacy for charitable giving has been a spectacular success – perhaps even more so in recent years, since the publication of The Life You Can Save. There are many thousands of people who, motivated by Peter’s writing, have pledged substantial proportions of their future income to charity.

There are two quite different conclusions we might draw from this. One possibility is that Peter has understood something about public messaging that the rest of us have not, and has somehow pulled off the trick of being at once a fearless philosophical truth-teller and an effective esoteric campaigner – in which case I’d like to humbly beg of Peter to teach the rest of us his secrets.

The other possibility is that Peter was perhaps too pessimistic in his assumption that most people would be put off charitable giving altogether by hearing how demanding our duties of beneficence can become in the face of grinding and pervasive global poverty. Perhaps what moves most of his readers to action is the bracing logic of “Famine, Affluence, and Morality”, not the watered-down ‘new standard of giving’. Even if, in practice, few can bring themselves to donate up to the point of marginal utility, the searing moral clarity of Singer’s Principle nonetheless makes it a powerfully motivating idea for many. Like many of our moral ideals, even though we are aware that we will inevitably fall short, it pushes us to do more, to be better, than we otherwise would.

Whatever the reasons for its effectiveness, Peter’s work has been a huge boon for humanity. And that is something for which we all have reason to be profoundly grateful.

End Notes

[1] For instance, it is often pointed out that, given the emphasis that the utilitarian tradition places on suffering (both on the capacity to suffer as a ground of moral status and on the avoidance of suffering as a central moral imperative), it is surely no accident that utilitarian philosophers have historically been at the forefront of advocating for the more humane treatment of animals.

[2] Peter Singer, “Famine, Affluence, and Morality”, Philosophy & Public Affairs, Vol. 1, No. 3 (1972), p. 231.

[3] Ibid., p. 231.

[4] T.M. Scanlon, “Contractualism and Utilitarianism” in A. Sen and B. Williams (eds.), Utilitarianism and Beyond, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), p. 116.

[5] Indeed, for some, being at least compatible with Singer’s Principle will function as an adequacy constraint on any more fundamental moral principle. Nonetheless, this is a point about the order of discovery, while the point I make in the following sentences is about the order of explanation.

[6] Gideon Rosen, “Notes on a Crisis: The Humanities Have a PR Problem”, Princeton Alumni Weekly, published online January 21, 2016: https://paw.princeton.edu/article/notes-crisis

[7] As calculated using the “Giving Scale” in the appendix of the book.

[8] Peter Singer, The Life You Can Save: How to Do Your Part to End World Poverty: 10th Anniversary Edition, p. 210 (Kindle Edition).

[9] Henry Sidgwick, The Methods of Ethics, 7th edition (London: Macmillan, 1907), p. 489.

[10] Peter Singer and Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek, “Secrecy in Consequentialism: A Defence of Esoteric Morality”, Ratio (2010), p. 38.

[11] For a spirited response to some of these objections, see Singer and de Lazari-Radek, “Secrecy in Consequentialism: A Defence of Esoteric Morality” and Singer and Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek, The Point of View of the Universe: Sidgwick and Contemporary Ethics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), Chapter 10.

[12] I take it that morally exhorting someone to donate 5.1% of their income to charity carries the misleading implicature that if they donate 5.1%, that will be enough, morally speaking.

[13] Dan Brock, “Truth or Consequences: The Role of Philosophers in Policy-Making”, Ethics (1987).

[14] I am not claiming that making the case for the defensibility or indeed the moral necessity of esoteric morality — as Plato, Sidgwick, and Singer have all done in various guises – isn’t itself a philosophical activity. Nor am I claiming that the question what the optimal content of a moral code for the masses would be is not a philosophical question. I am merely claiming that publicly promoting ethical positions that one oneself does not take to be true (or at least saying things in public that come with a conversational implicature of things one believes to be false) is to be engaged in a different kind of activity from that of doing philosophy.

[15] The Methods of Ethics, op. cit., p. 490.

I am very pleased that Johann has allowed Pea Soup to publish the text of his talk at the conference that Princeton’s University Center for Human Values hosted on my retirement from the university. Johann’s talk was just what a talk at a retirement conference for a philosopher should be: kind words blended with probing questions. Fortunately, Johann’s questions will now be available for others to ponder, and perhaps to help me in finding a convincing response.

Johann explores the tension between the roles of philosopher and a public campaigner – a tension I have felt all my life, not only in regard to my views on global poverty, on which Johann focuses, but also in my work on the ethics of our relations with animals, and in bioethics as well. The tension exists when I teach, as well as when I am writing, but to keep this comment brief, I shall confine my remarks to my role in doing research and writing. I will give only a brief response to Johann’s comments on my philosophical ecumenicalism and say more about his comments regarding esoteric morality.

1. Ecumenicalism

Johann’s aim, in what he says about ecumenicalism in philosophy, is to persuade us that “there are sometimes tradeoffs between explanatory depth and generality, on the one hand, and the breadth of appeal that comes from an ecumenical approach, on the other.” I agree. The way to handle this, I believe, is to write different works for different purposes. I wanted “Famine, Affluence and Morality” to influence as many readers as possible, and that precluded deriving its conclusions from utilitarian premises, let alone seeking to establish those premises. It owes much of its success to its brevity and to the fact that it makes an argument that is straightforward yet challenging. These virtues led to it being reprinted in many anthologies used in teaching practical ethics, so it reached many undergraduate students. Eventually the drowning child in the shallow pond became iconic, like the trolley problem, and was discussed by people who had never studied philosophy.

I attempted several times to show how one might argue for utilitarianism. The version I am most satisfied with is The Point of View of the Universe, (Oxford University Press, 2014), which I co-authored with Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek. It is a substantial book, and unsurprisingly, it has reached far fewer readers, and had much less influence, than “Famine, Affluence and Morality.”

My view, then, is that although the tension between a broad appeal, and explanatory depth, may be impossible to overcome in a single piece of writing, it can be overcome through a larger corpus of work.

2. Esotericism

Johann rightly notes that in my recent public advocacy, my standard for what people ought to give to help those in extreme poverty is lower than the standard I argued for in “Famine, Affluence and Morality.” (More precisely, it is lower than either the standard required by either the strong or the moderate version of the argument I put forward in that article.) Johann notes that I have, with Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek, defended Sidgwick’s view that esoteric morality is defensible, and sees my advocacy of a lower standard to be a form of esoteric morality. Yet he also comments that I am quite open about what I am doing – especially in The Life You Can Save – and that, despite this, I have had some success in persuading people to give to effective charities. (Though to say that my success has been “spectacular” is too generous, given the huge and still largely untapped potential for effective giving in wealthy countries.)

Johann offers two possible conclusions we could draw from this situation: that I have “understood something about public messaging that the rest of us have not, and [have] somehow pulled off the trick of being at once a fearless philosophical truth-teller and an effective esoteric campaigner” or that I have been “ too pessimistic in [my] assumption that most people would be put off charitable giving altogether by hearing how demanding our duties of beneficence can become in the face of grinding and pervasive global poverty.”

Here’s what I came to believe, in the more than 30 years of talking to people about giving that followed “Famine, Affluence and Morality,” but preceded The Life You Can Save. If you tell people that unless they meet some highly demanding standard, they are failing to do their duty, and are bad people, all but a tiny number of heroic people will be unresponsive to appeals to give. If, however, you tell them that, although there is some sense in which they should be giving to a very demanding standard, if they meet a less demanding standard – but one still clearly above what most people are giving – I and others will praise them for the good they are doing, rather than blame them for not doing more, then they will meet or exceed that less demanding standard. I’ve seen that happen many times.

Have I, then, pulled off the trick Johann is referring to? Perhaps I have been able to combine philosophical truth-telling and effective campaigning because I have not really been practicing esoteric morality. As Johann notes, in The Life You Can Save (the revised edition of which, incidentally, you can download free from http://www.thelifeyoucan save.org), I do spell out the arguments for a demanding standard, but then the reader reaches Chapter, 9, entitled “Asking too much?” and Chapter 10, “A realistic standard.” In these two chapters I address the problem with demanding standards, explain the dilemma that Johann sets out, and say why I am proposing the standard that permits them to donate a modest proportion of their income and feel OK about that – but, of course, allows and even encourages him to do more.

In thus differentiating between whether an action is right or wrong, and whether we should praise or blame the agent, I am following Sidgwick’s suggestion that we can best promote moral progress by “praising acts that are above the level of ordinary practice and confining our censure … to acts that fall clearly below this standard.” (The Methods of Ethics, 7th ed., p.221; see also The Point of View of the Universe, pp.320-21.) I extend Sidgwick’s suggestion to cover also the idea that those who give at a level clearly above common standards practice need not suffer from feelings of guilt, because their giving does not meet the right, extremely demanding, standard.

Behind this approach to praise and blame, both for others and for oneself, lies a consequentialist view of morality, in which we are more likely to ask a question like “Of all the good I could have done, how much have I done?” rather than “Have I fulfilled my duties of beneficence?” This is not exactly scalar morality (see Alastair Norcross, Morality By Degrees, Oxford University Press, 2020), but it is more sympathetic to that view than a deontological morality is likely to be.

I’m delighted to take part in this discussion involving two former—and much missed!—colleagues, Johann Frick and Peter Singer. And I very much appreciate the invitation to do so. Although I agree with almost everything in Johann’s excellent (and philosophically stimulating!) tribute to Peter, I want to begin by noting one of the few things that I think is potentially misleading, at least by way of omission. From Johann’s tribute, one might easily get the idea that the persuasiveness of Peter’s great paper “Famine, Affluence, and Morality” is due more or less entirely to the immense plausibility of ‘Singer’s Principle,’ viz. “If it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought, morally, to do it.” This is, as Johann says “a mid-level principle.” As such, it contrasts both with (on the one hand) judgments about particular cases and with even more general and fundamental principles, such as the uber act utilitarianism principle, viz. that one is morally required to act so as to maximize expected utility (or something in that neighborhood). In his paper, Johann picks up on the interesting contrast between Peter’s commitment to act utilitarianism and his willingness to make use of mid-level principles in his work in applied ethics. (For the record, I join both Peter and Johann in finding ‘Singer’s Principle’ immensely plausible, while I join with Johann and depart from Peter in rejecting act utilitarianism.) As far as I recall, nothing in Johann’s paper picks up on the contrast between either mid-level level principles or fundamental moral principles (on the one hand) and judgments about particular cases (on the other hand). *BUT* I believe (although this is of course an empirical question) that the great persuasiveness of “Famine, Affluence, and Morality” was due in large part not only to the great plausibility of Singer’s Principle but also to the great plausibility of even less abstract and more concrete judgments—for example, the judgment that one is morally obligated to save the child from drowning (even at the cost of getting one’s clothes muddy), or the judgments with which Peter provocatively opens the paper, that we are morally obligated (in November 1971) to contribute more to relieve the tremendous suffering then taking place in East Bengal. I think that the fact that much of the persuasiveness of Peter’s work in applied ethics (not just in this paper, but elsewhere as well) depends on the intuitive plausibility of various judgments about cases, notwithstanding his own act utilitarianism, raises a number of interesting questions about how various things in Peter’s work fit together that are at a minimum quite similar to the kinds of issues that Johann raises. I will spell this out in a follow-up comment.

Here is (part of!) the promised follow-up to my earlier comment—in his piece, Johann is concerned with not only (or even primarily) the rational power of Peter’s arguments, but their psychological potency—their ability to actually persuade people of their conclusions. (I assume that, although these things are of course not unrelated, in Peter’s work or elsewhere, the rational potency of arguments and their psychological potency can come apart, and in both directions: an argument might be rationally compelling, but not psychologically compelling, or vice versa.) Suppose that someone who had never read “Famine, Affluence, and Morality,” and who was unfamiliar with its tremendous influence, and the history of critical discussions of it (etc.) simply read Johann’s tribute. Such a reader might easily get the impression that the psychological potency of the argument is due more or less entirely to the plausibility of Singer’s Principle. And in fact, that way of thinking about it is entirely faithful to the way that Peter presents the rational structure of the argument in the original paper. But of course, the original paper opens not with a presentation of Singer’s Principle but with a description of the tragedy that was then taking place in East Bengal. (The paper’s opening sentence: “As I write this, in November 197I, people are dying in East Bengal from lack of food, shelter, and medical care”). We are then invited to agree with a moral judgment: that we are acting morally wrongly in not giving far more than we currently are to relieve this terrible suffering (or something in that neighborhood). Notice that this moral judgment is neither a judgment that a fundamental moral principle is true, nor that a mid-level moral principle is true; indeed, it is not even “a judgment about a particular case,” as ethicists and epistemologists standardly use that expression. (As Shelly Kagan points out in “Thinking About Cases,” a judgment about a hypothetical case such as the Trolley Problem or the Organ Harvesting case is actually a judgment about a *type* of event, and so already has some generality.) In contrast,to all of those, the judgment from which Peter begins is a judgment about a *token* event (in this case, a token omission)—one’s failure to respond in a certain way to what is actually taking place in East Bengal. It is only after this immensely plausible judgment has been offered to us that Singer’s Principle is brought on the scene, as a way of accounting for what many readers will already be thinking is true. I suggested that much of the psychological potency of the paper depends on this way of proceeding. I also suspect—although here as elsewhere, Peter should correct me if I’m wrong!—that Peter himself must surely have been aware of this—after all, just as it’s no accident that Peter didn’t begin the paper by appealing to act utilitarianism, for the reasons that both he and Johann rehearse, surely it’s also no accident that he began the paper by talking about the concrete case of East Bengal, given his concern with actually moving his readers in a desired direction. In my previous comment, I also suggested that this leads to some interesting tensions between various aspects of Peter’s work (or at least, questions about how various aspects of how Peter’s work fits together). These mirror some of the issues raised by Johann. But I will once again put them off to a further comment…

I have one little remark about ecumenicalism. When I was teaching “Famine, Affluence, and Morality”, one of my students brilliantly asked why we need the argument for the conclusion Singer was advocating for, when many systems of belief (religious or otherwise) already incorporated the conclusion into their practice. For instance, Islam has one of its fundamental pillars ‘zakat’, which requires the wealthy (which can easily be translated into the ‘disposable outcome’ in Singer’s argument) distribute 1/40 of their wealth to the worst off. My response at the time to the student was twofold: (i) even if we are unwaveringly subscribing to the conclusion, we need to understand where the conclusion comes from, be it for stability of behavior or generalization to the behavior to like-circumstances and (ii) ecumenicalism–we want not only Muslims, but everyone to subscribe to the conclusion or, in other words, we want those who are not subscribing to the conclusion to be compelled to do so.

So not only do I agree with Frick that ecumenicalism is one of the most important features of Singer’s arguments, but also that it has to be that way, if we want to achieve the conclusion, which again may be shared by utilitarians, deontologist and religiously-driven morals.

I also thank Frick and others who made this post available. Truly a wonderful talk and a writeup!

Many thanks to Peter for this generous and illuminating reply.

Since I don’t disagree with anything that Peter says in response to my remarks about his philosophical ecumenicalism, I will focus on the second part of his reply, about the tension between being a philosopher and what I called an “esoteric campaigner”.

IS IT ‘ESOTERIC MORALITY’?

First, let me speak briefly to a conceptual question. Is what Peter is engaged in in the final chapter of The Life You Can Save a form of esotericism about morality? I suggested that it is, albeit a non-standard one, whereas in his response to me Peter disputes that label (though elsewhere, e.g. in his article with Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek, “Secrecy in Consequentialism: A Defence of Esoteric Morality”, Peter seems more ready to describe strategically moderating one’s message regarding how much people ought to give to charity as a form of esotericism about morality. See in particular pp. 37-38 of that piece).

The disagreement may stem from which of two typical characteristics of esoteric morality one chooses to treat as *essential*:

(1) One publicly promotes a moral standard that is different from what one believes to be true, because this is what one believes will have the best consequences.

(2) One hides or dissembles one’s beliefs about what morality actually requires.

Of these two characteristics, the former seemed to me more central than the latter, which is why I made it part of my definition of the esoteric campaigner; the latter, it seems to me, is a claim about what it would take to do esoteric morality *as effectively as possible*, but perhaps not a necessary condition for being engaged in esoteric morality itself.

Peter and I both agree that he’s *not* doing (2). Even in his later work, Peter is admirably upfront that he continues to believe in Singer’s Principle, which is far more demanding than the “new standard of giving” that The Life You Can Save advocates for.

Is he doing (1)? I was inclined to say “yes”. But Peter’s response suggests that he may deny this as well. Peter might deny that he is doing (1), because, as he sees it, in offering up his “new standard”, he isn’t really answering the same question as Singer’s Principle. He isn’t answering the question “What does morality demand of me?” but rather “How must I act so that I should be praised rather than blamed for my behavior?”.

What is really off-putting to people, Peter suggests, is not so much the thought that morality is very demanding, but rather that they should be *blamed* for not meeting that exacting standard, even if they are doing far more than the vast majority of people around them.

QUESTIONS ABOUT BLAME AND BLAMEWORTHINESS

Peter’s response depends on drawing a fairly sharp distinction between the question “how much would it be morally *right* for me to give to charity?” and the question “how much must I give to charity so that I am not to be *blamed* for not giving more?”.

He further expands on this in The Life You Can Save: “We use praise and blame to influence behavior, and the appropriate standard is relative to what we can reasonably expect most people to do. Hence praise and blame, at least when they are given publicly, should follow the standard that we publicly advocate—that is, the standard, public advocacy of which can be expected to have the best consequences, not the higher standard that we might apply to our own conduct. We should praise people for doing significantly better than most people in their circumstances do, and blame them for doing significantly worse. If you have done more than your fair share, that must at least lessen the blame you deserve. If you have gone beyond the usual moral standards, we should praise you for doing so, rather than blame you for not doing even more.” (The Life You Can Save, Kinde Edition, p. 212).

This reply raises several further questions for me. Let me make a couple of points:

1. Peter’s response focusses on the instrumental effects of praising or blaming people. We should praise people for acting better than most, and thereby encourage more such behavior; we should blame people for doing the opposite, and thereby discourage such behavior.

While I agree that questions about the instrumental effects of expressing praise and blame are important, I don’t think that this is all there is to blame and blameworthiness.

Blaming someone is not reducible to public censure. While in some cases, I may express blame by publicly rebuking a person, I can also blame someone “in foro interno”, without communicating or expressing my blame to them or to others. This “internal” sense of blame refers not to a communicative act, but to an attitude or judgment. Moreover, since the mere holding of such attitudes need not have any effect on other people, it is unclear whether its moral appropriateness could be a function of its instrumental effects – it may have none.

2. Even in cases where blame is publicly expressed, I don’t believe that the question whether the blame is *appropriate* can be reduced to forward-looking questions about the instrumental effects of *expressing* blame. Whether blame is appropriate, to my mind, is primarily a backward-looking question, which concerns the *fittingness* of this response to what the agent did (e.g. their culpable wrongdoing) or the attitudes they expressed (e.g. a lack of concern or respect). There could be good consequentialist reasons not to public express blame in cases where doing so risks being counterproductive. But that is no reason to think that such blame could not nonetheless be fitting or justified.

3. Now that we have the distinction between the fittingness of blame and the consequences of publicly expressing blame clearly in view, I have a few questions for Peter:

Suppose that I am currently donating 10% of my pre-tax income to charity, which is more than the “new standard of giving” asks me to give. Still, I could be giving *considerably* more and could thereby do a huge amount of good in the world, without sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance. Would it really be inappropriate for a member of the global poor to blame me for not doing more? Of course, it may be counterproductive, and hence imprudent, for them to publicly *express* their blame. And of course it will be true that others, who are doing far less than me, are much more to blame than I. Nonetheless, if we reject (as you do) ‘fair share’ views, like Liam Murphy’s, or views on which morality is a lot less demanding than Singer’s Principle assumes, then can we really deny that their blame would be justified?

By the same token, were I to feel guilty about not doing more, can we really say that such feelings of guilt would be inappropriate or unjustified? (Granted, such feelings may not be especially *helpful*, if they don’t move me to do more but instead sap my morale. And perhaps, for that reason, it would be wrong and counterproductive for others to try and induce such feelings of guilt in me). But can we really deny that I am seeing things aright if I blame myself for not doing more?

4. Suppose you agree that we must answer these questions in the negative. Then I do wonder whether there isn’t some amount of strategic obfuscation in telling others that “although there is some sense in which they should be giving to a very demanding standard, if they meet a less demanding standard – but one still clearly above what most people are giving – I and others will praise them for the good they are doing, rather than blame them for not doing more.” To many people, this will sound like you’re saying that if they simply meet the less demanding standard of giving, then they will be *blameless* for not doing more. But if you answer the question in 3) in the negative, then this *isn’t* what you are really saying. And this strategic obfuscation is psychologically quite significant: while people care about not being publicly rebuked by others, this isn’t all that most of us care about: we also care about behaving in a way that others couldn’t *justifiably blame* us for, whether they public express this or not.

A (shorter!) response to Tom Kelly is next…

Tom, thanks so much for your kind words about my post! You’ll be glad to hear that I entirely agree with you about the force of intuitive judgments about concrete cases – both the historical realities of the East Bengal Famine and Peter’s famous Pond Case – and the crucial work that they do in making Peter’s paper so compelling. Indeed, whenever I teach “Famine, Affluence, and Morality”, I begin with a fairly detailed recounting of the events of 1971, accompanied by newspaper photographs of the time. By the time we get to the philosophical substance of Peter’s arguments, the students are usually *more than ready* to agree that we citizens of affluent countries ought to be doing far more than we currently are to alleviate the effects of comparable disasters in the present. Moreover, I always make the point that there are at least two different ways of reading Peter’s argument: Either, as a deductive argument with Singer’s Principle as its major premise, or as an argument by analogy, which first has the reader register how *obviously* wrong it would be to fail to rescue the drowning child, and then challenges them to come up with any morally relevant difference between this and failing to save the life of a distant stranger by not donating to charity.

And what is true of Peter’s work on our duties of aid is, for me, even more true of his work on animal ethics. Indeed, I left the Princeton Farewell Conference (which included a number of tributes by animal rights activists, including a very powerful talk by Ingrid Newkirk, the president of PETA) thinking that while Peter’s moral case for the more humane treatment of animals was intellectually cogent, what moved me even more was the eloquence of the empirical facts that he marshals – e.g. about the horrific conditions in factory farms or in animal laboratories. One feels very strongly that — whatever the exact philosophical explanation — there simply *has* to be something wrong with these practices. And more psychological powerful even than that were the images of animals that Ingrid and others showed; both of their suffering but also of their enormous capacity for joy, for community, etc.

Like you, I’d be very curious to hear Peter speak to the role that our intuitive reactions to such concrete cases play for him, and how they fit into his philosophical method and moral epistemology.

Johann, thanks for your reply! I’m glad to hear that we agree about the force of intuitive judgments about concrete cases – both the historical realities of the East Bengal Famine and Peter’s famous Pond Case – and the crucial work that they do in making Peter’s paper so compelling. Like you, my sense is that this is every bit as important if not more so when it comes to the influence of Peter’s work on animal ethics.

OK, as promised, and following up on my two earlier posts, here is where I think there is some tension (I’m not sure if that’s exactly the right word) between the way in which some of Peter’s most influential work in applied ethics derives a great deal of its persuasive force from intuitive judgments about particular cases and his more theoretical work in ethics. [I’m just going to speak to this issue, and then later make clear how I think it relates to Johann’s paper.]

I think it’s notable here that another persistent theme in Peter’s work has been *skepticism* about giving significant weight to relatively low level, intuitive judgments about cases. Indeed, this skepticism is very much in play in a paper published two years after “Famine, Affluence, and Morality” (1972), his “Sidgwick and Reflective Equilibrium” (1974). There, Peter is concerned to among other things defend utilitarianism from the charge that it must be incorrect because it simply gives the wrong answers in some particular cases. He argues that the method of reflective equilibrium is not the correct methodology for doing ethics, in part because it’s overly conservative, and in effect loads the dice in favor of our pre-theoretical intuitions. (Of course, this paper is published just a few years after a Theory of Justice, where Rawls popularized the method of RE among moral and political philosophers. To my knowledge, Peter was the first person to raise the ‘conservatism’ charge against the method although certainly not the last. And interestingly, its putative conservatism was considered a virtue by some of its proponents, notably our late and much missed colleague Gil Harman, who had learned from his teacher Quine that belief revision, when done correctly, should be conservative! OK, end of digression…)

In any case, in that paper, the correct method is, according to Peter…. Sidgwick’s! At least, as he understands Sidgwick’s method: roughly, reason from self-evident first principles, overturning ordinary intuitions as necessary. On Peter’s suggested methodological picture, we should privilege our judgments about what he calls “moral axioms” over our particular moral judgments. This is because our particular moral judgments are more likely to be artifacts of various cultural and psychological biases. (I critically discuss some of these ideas about methodology, along with more recent echoes from other writers, in my book Bias, pp.193-195.)

But this theme—that we should give less weight to intuitive judgments about cases than many philosophers would give—is certainly not limited to this early paper. For example, it reappears in a big way 35 years later, in “Ethics and Intuitions” (2005). Now, it’s not surprising that a committed act utilitarian like Peter would not want us to give too much weight to our intuitive judgments about cases. For some of us, the best version of the Organ Harvesting Case is just a straight *counterexample* to act utilitarianism. (I confess that I’m in this camp.) So it will be tempting for the act utilitarian to accuse those of us who think such things as being in the grips of a bad methodology. (I should note here that despite the fact that it’s the target of the earlier paper, one doesn’t have to be employing ‘the method of RE’ here—indeed, although I don’t share Peter’s act utilitarianism, like him I am skeptical of the idea that the method of RE can supply a comprehensive epistemology or methodology for ethics, as some of its proponents claim—my own doubts are contained in a 2010 paper co-authored with Sarah McGrath, “Is Reflective Equilibrium Enough?”

So the tension—or maybe better, the irony—that I see for Peter is this. On the one hand, it’s plausible that much of his great influence, and his success in moving people where he wants them to go with respect to first-order morality, depends on their giving a great deal of weight to their intuitive judgments about cases. But on the other hand, Peter’s corpus also purports to provide reasons for not giving so much weight to our intuitive judgments about cases, which is at a minimum a practice we should view with suspicion. So perhaps if people followed Peter’s teachings about privileging their very general and abstract judgments about morality, they *wouldn’t* be moved in the way that they have been by his work in applied ethics. Now, I expect that Peter would say that you can get to the same (correct!) place by reasoning in a top-down way, from the act utilitarian principle. But of course, this doesn’t speak to the psychological question, which is largely empirical—if people gave up on or at least sharply discounted their intuitions about particular cases, maybe they would *not* in fact be moved as much as they are by Peter’s work in applied ethics, given the way in which much of that work relies on our reactions to cases (even if they would be so moved if they were fully rational).

I trust the connections with Johann’s paper are clear here. Here is one of them: perhaps Peter’s teachings about the general untrustworthiness of our moral intuitions (at least, when they are not derived from a moral axiom) is itself a candidate for being part of ‘esoteric morality.’ Perhaps if it became widely accepted that we should give less weight to our intuitive reactions to animal suffering, or instances of famine, etc., this might have morally bad psychological effects, when judged from the perspective of the true moral theory.

Thanks very much to Johann for a fascinating discussion of Peter’s work, and to everyone, especially Peter, for the discussion.

I had a brief comment about blame, in the light of Johann’s most recent response to Peter. Like Johann, I was struck by Peter’s suggestion that if morality demands that X gives n, most people give, m, which is much less than n, but X gives more than m but less than m, X should be praised. As Johann suggests, we might distinguish whether praise is instrumentally effective or good, or warranted. Perhaps X warrants blame for violating the duty to give n, but should be praised, because praising X will encourage others to do better than they currently do, for example.

In contrast, though, I think that we sometimes warrant praise even when we fail to do what morality demands. Suppose that Johann only committed one very minor wrong in the whole of his life. Other than that, he never violated a moral requirement. I think he warrants praise for living a life almost completely unblemished by wrongdoing. I also think that X might warrant praise for doing better than m, given how tempting it might be to give even less. They at least warrant praise for not giving into the temptation to give less.

Even in failing to meet a moral demand, then, I think that people might warrant praise for the character or fortitude that it took to do better than expected. So I don’t find Peter’s view that we should praise people for doing better than others as problematic as I think Johann suggests.

Some might disagree, suggesting that blame is always warranted whenever a person fails to do what they are required to do without justification or complete excuse. Clearly, something is warranted in the light of such failure – some kind of acknowledgement that the person failed to do what was required of them. But perhaps blame is not always apt in such cases.

I have a suggestion in a similar spirit to Victor Tadros’s remarks.

Peter Singer’s reply to Johann Frick’s concerns about esotericism appeals to a distinction between right and wrong, on the one hand, and praise and blame, on the other. Donating (say) 10% of one’s pretax income is wrong, since it falls short of the true moral standard set by Singer’s Principle. But we should praise such donation.

Frick raises the worry that even if praise of 10% donation has good effects, it is fitting to blame, rather than praise, such donation, since it falls short of a moral requirement. Here Frick draws a plausible distinction between whether it is good to praise or blame and whether praise or blame is fitting (or appropriate).

I wonder though whether Singer’s final remark might suggest a reply to this worry. Suppose we adopt a view along the lines of scalar consequentialism, attaching less significance to rightness and wrongness and more significance to goodness and badness. Given this view, it may be natural to say that like goodness and badness, the fittingness of praise and blame comes in degrees. If you do something good, praise is fitting. If you do something really great, even greater praise is fitting. This does not conflate praise that has good consequences with praise that is fitting: it maintains that the standards for fitting praise come in degrees, corresponding to the goodness of the act being praised.

Johann, thank you for these excellent, thought-provoking reflections, and thank you, Peter, for the great inspiration you’ve provided to so many philosophically inclined campaigners and campaigning philosophers!

I very much appreciate the invitation to contribute to this discussion. Here are some of my reactions to your thoughts, Johann:

You write that what many of us are ultimately after in doing philosophy is a form of understanding: “We want to understand, at the deepest and most fundamental level, the nature of reality […].” This is certainly one of my objectives, but I’m not sure I do or should value mid-level understanding much less than fundamental understanding, whether in philosophy or in the natural and social sciences. For one thing, mid-level insights can be more fundamental in terms of the order of discovery (as you note). It’s not obvious to me that fundamentality in terms of the order of explanation matters more as far as the value of understanding is concerned.

Moreover, fundamental moral understanding seems harder to attain than mid-level moral understanding, which may provide instrumental epistemic reason to prioritize mid-level moral investigations. Practical reasons may thus favor prioritizing mid-level investigations too: If mid-level investigations tend to produce more certain conclusions, we may be able to make greater progress in terms of knowing-what-to-do-and-actually-doing-it by prioritizing them over fundamental investigations.

You note that “Whatever else philosophy is, it consists in a good-faith pursuit of the truth […].” Indeed, the philosopher is a lover of theoretical, contemplative wisdom. I think the philosopher is also, in equal measure, a lover of practical wisdom. Practical wisdom, one may argue, involves a commitment to actually doing what matters, and to doing what matters the most in case of trade-offs. Relatedly, your remark that “Being an esoteric campaigner may be honorable and even praiseworthy” perhaps underestimates the strength of the practical reasons we have to be (potentially esoteric) campaigners. Singer’s Principle applies to how we allocate our time as philosophers too. In a world where thousands of children and billions of animals suffer and die needlessly every day, and where astronomical future suffering may be on the line, the moral stakes seem very high indeed. (Thoroughgoing nonaggregationists deny this, of course, which allows them to avoid the many troubling conclusions that arguably result from “scope-sensitive” ethics.) If being an esoteric campaigner is what it takes to effectively counteract the ongoing and expected catastrophes in this world, it is unclear that we sacrifice anything of comparable importance by engaging in esoteric campaigning (despite the many objections to it). In other words, our reasons to act against ongoing and expected catastrophes may outweigh the reasons to avoid esotericism. (Cf. David Enoch’s recent paper, “Politics and Suffering,” Analytic Philosophy, 2023, which makes an argument that may often apply outside of politics too. David claims: “[…] in the political context, the stakes in terms of suffering are usually extremely high, so that any other considerations are almost always outweighed. Put in moderately deontological terms: the high stakes carry most political decisions across the thresholds of the relevant deontological constraints.”)

However, I don’t think much esotericism (if any) is called for in practice. Normative uncertainty, as well as peer disagreement, should temper our confidence in highly revisionary views about what constitutes a sacrifice of comparable practical importance. If public audiences still find our proposed imperatives “offputtingly demanding,” say, that provides us with some evidence that they would not agree with us on their best reflection. We should not be so confident that we are right. (People who self-select into moral philosophy may have particular pretheoretical inclinations that drive their work.) In any case, though, we can argue that while we personally lean towards a more radical view, we think more moderate views may still entail that one should take impartial beneficence more seriously than most people currently do. The literature in the social psychology of persuasion and the lived experience of moral activists do not, in general, support concealing one’s more radical views on strategic grounds (quite the opposite, I think). But even if they did support esotericism, we should still plausibly comply with norms of truthfulness in both academic and public discourse. In addition to being of great intrinsic importance, such norms are extremely instrumentally important, given our fallibility and the urgent need for moral error correction.

Responding to Victor and Milan above:

Thanks to both Victor and Milan for your excellent comments. I think they point to a way in which what I said in my initial response to Peter may have given the wrong impression.

I didn’t mean to suggest that “blame is always warranted whenever a person fails to do what they are required to do without justification or complete excuse”. That view is certainly too strong, for the reasons Victor spells out. I agree that “even in failing to meet a moral demand, people might warrant praise for the character or fortitude that it took to do better than expected.”

What I do want to insist on is that when a person falls short of what they are morally required to do, without justification or excuse, there is at least an *open question* whether this warrants blame. And this question, I maintain, is not answered simply by pointing out that they are doing better than most, or that praising them would have consequences that are strongly socially beneficial, whereas blaming them would be counterproductive. Those may be good reasons not to engage in public criticism; but it seems like the wrong kind of reason to think that blame couldn’t be warranted.

This distinction seems to me particularly important in cases like those of billionaire philanthropists, such as the Gateses or Warren Buffets of the world, which Peter discusses in Chapter 10 of The Life We Can Save. In absolute terms, these individuals have given very large sums of money to charity, and have pledged to give yet more in the future. Yet, relative to their gargantuan fortunes, it is clear that they could be doing vastly more and are falling very far short of the demands of Singer’s Principle. As Peter himself writes: “it is obvious that the Gateses, for all their generosity, don’t live by the idea of the equal value of human life.” (p. 214). About this case, Peter writes further: “So should we praise the Gateses for exceeding, by a very long way, what most people, including most of the super-rich, give, or should we blame them for living in luxury while others still die from preventable diseases? (…) I think we should praise them for giving as much as they have, and for setting an example for other billionaires.” (p. 214)

I’m entirely with Peter, as long as we’re clear that what we’re talking about here is the act of *publicly praising* the billionaires, ‘pour encourager les autres’.

As for my private judgment about whether this truly constitutes a level of generosity that deserves our praise and admiration, and that would make it inappropriate for the global poor to (privately!) blame these super-wealthy for not doing more, you can probably imagine what my answer would be. Suffice it to say that I don’t believe that the factors that can sometimes make a morally deficient action nonetheless praiseworthy – e.g. that it took a lot of character or fortitude or personal risk or sacrifice to do as much as one did – are especially pertinent here.

This is a really fertile exchange, and my primary remark is gratitude to all. But I’m inclined to echo Johann’s thoughts about esotericism. Really, the worry I have reflects a deep form of mistrust that enters my mind when I start thinking about utilitarian reasons for saying (writing) anything.

On the generous side, I’d like to read Peter the way Milan Mosse does above. That is, rather than drawing a sharp deontological line around what one is obliged to do, and then saying that all actions that fail to live up to that standard are failures, we should read him as saying that giving until more giving would be counterproductive would be the Best way to live, but that there’s a spectrum of better-than-normal behavior, and anything substantially above the baseline deserves praise. That seems to allow Peter to make his points without any real tension. (As a matter of substance, I’m fairly convinced by Angus Deaton’s critique of Peter’s work, and I think that this focus on individual giving in highly complicated political and economic systems is misguided and counter-productive of the good. But let’s put that to the side.)

On the other hand, on the mistrustful side, I find myself worried that Peter, like any good utilitarian, is always assessing his statements not with an eye to truth, but with an eye to effectiveness. If that’s the case, then I quickly fall into a deep well of mistrust with regard to anything he says. That’s not a problem insofar as one can decide for oneself whether the inferences they make seem valid; it is a problem insofar as they are making factual assertions that we are to take on trust. What brings me out of it are two things: (a) I’ve met him and he just doesn’t seem that duplicitous or manipulative (he’d have to be uncannily good at it); and (b) there’s the Milan reading that allows us to make sense of his position on praise and blame in a way that seems much less manipulative than Johann’s interpretation. But it’s a least an unfortunate side-effect of utilitarianism that a level of distrust with regard to any argument a self-identified utilitarian makes (and undermines confidence in general, as it provides one more basis to worry that those one might be dealing with are liars).

Alec, thanks for joining the discussion! Since you comment favorably on Milan’s positive proposal above, which I hadn’t yet explicitly responded to, let me stay for a moment with that part of the dialectic. Adriano, thanks so much for your comment as well – I promise to come back to it!

Milan makes the following proposal: “Suppose we adopt a view along the lines of scalar consequentialism, attaching less significance to rightness and wrongness and more significance to goodness and badness. Given this view, it may be natural to say that like goodness and badness, the fittingness of praise and blame comes in degrees. If you do something good, praise is fitting. If you do something really great, even greater praise is fitting. This does not conflate praise that has good consequences with praise that is fitting: it maintains that the standards for fitting praise come in degrees, corresponding to the goodness of the act being praised.”

I think this is an interesting proposal, and I agree with Milan that praise- and blameworthiness come in degrees. Nonetheless, I think the proposal will require pretty significant qualifications. As I suggested in my response to Victor, while I agree that an action may be praiseworthy even if it falls short of some non-scalar standard of moral rightness, I don’t believe that determining whether the action is praiseworthy or blameworthy (and if yes *how* praiseworthy or blameworthy it is) could be as simple as seeing how much good it does, as a simple scalar view might have it (– not that I take it that this is what Victor was suggesting!).

My example of the billionaire, who donates a large absolute amount to charity but which amount only to a tiny fraction of his overall wealth, already makes this point quite effectively, I think. However, for an even clearer example, consider a modified version of one of Peter’s own cases.

Suppose there are 10 children drowning in a shallow pond. I am standing by the edge of the pond, along with nine other potential rescuers. The nine others simply walk away, leaving me to deal with the situation by myself. Suppose I rescue five of the children (assume, perhaps unrealistically, that there is a small but *constant* marginal cost to rescuing each extra child); but then I decide to call it quits, leaving the remaining five children to drown.

I have done a lot of good here – five children are alive that, but for my efforts, would have drowned! Yet, it seems to me, my behavior is clearly *not* praiseworthy but rather quite blameworthy, *despite* the fact that I did a lot of good. I really ought to have saved all 10 children. Unlike the types of cases that Victor was concerned with, this really isn’t the kind of case where my doing less than I ought to have (or less than the best) might nonetheless be praiseworthy because it required exceptional character or fortitude in the face of temptation or the assumption of significant risk or sacrifice.

I’m also a quite leery about using statistical averages about “the way people usually behave” to set a baseline for praise and blame, and to say that anything substantially better than the baseline deserves praise (that’s one way of reading what Alec was suggesting). Social psychology teaches us that, given the right situational cues, even psychologically normal people can behave pretty awfully. In Stanley Milgram’s experiments, 65% of participants administered (what they believed to be) the maximum (fatal) shock. To my mind, this behavior is no less horrifying and blameworthy for being so common. I think it would be setting the bar too low to praise someone for simply having done “better than average” in such a case.

Thanks to everyone for the fantastic discussion so far! I want to first express my own gratitude to Peter for being a wonderful teacher, mentor, and landlord (he didn’t unexpectedly raise my rent even once)!

I just want to pick up on one strand of the discussion, which has to do with the question how Peter could be “at once a fearless philosophical truth-teller and an effective esoteric campaigner.”

Suppose we understand what Peter is up to in his role as a philosopher-cum-campaigner in the following way: Peter is *telling* people the truth that what they ought to give is governed by the Singer’s Principle. But he is also *advising* people, based on his understanding of people’s psychological propensities, that they give 10% of their income.

This position looks to me consistent, and it need not draw any support from claims about the praiseworthiness/blameworthiness of individuals. All Peter needs to say is that it is sometimes better to advise people to do what which deviates from morality. Importantly, *advising* someone to do something that deviates from morality need to commit the advisor to *lying* about the facts of morality. If someone seeks my advise about whether to break a promise for no good reason, and I know that by advising her to keep her promise, it will cause her to do something even more horrendous, then I can consistently say: “The truth of the matter is that it is wrong to break your promise. But given your weird psychological propensities, I advise you to break it.”

What a wonderful discussion!

Peter kindly suggested that I might flag my current book project, *Beyond Right and Wrong*, which I take to be emblematic of (as he put it) “a consequentialist view of morality… [that] is not exactly scalar” but tending in that direction. I outline the project here:

https://www.goodthoughts.blog/p/beyond-right-and-wrong

It’s relevant to several threads in the ongoing discussion here. For example, re: ecumenicalism, my fourth chapter introduces *beneficentrism* as a convenient label for the moderate (“utilitarian-lite”) position that gives significant weight to (aggregate) impartial welfare, *without* necessarily committing to rejection either options or constraints. So it’s a view that many non-utilitarians should be happy to get on board with. But it’s also sufficient to establish most of the really important practical implications that utilitarians care about (e.g. strong reasons to engage in effective altruism).

re: esotericism, Part I of my book argues that we should focus less moral and philosophical attention on questions of duty (or the precise location of deontic boundaries), and more on telic questions about what is most worth aiming at. And here I don’t think there’s anything esoteric about Singer’s work. He’s very clear about what he thinks is most important, or worth prioritizing. He encourages people to take moderate steps towards achieving that, because demanding more could be counterproductive. I don’t see this as esoteric in the slightest. To think otherwise, it seems you must interpret this encouragement as expressing implicit deontic commitments (e.g. as to the permissibility of the encouraged act). But I see no reason to read in such implicit deontic commitments. As I read Singer here, he is encouraging his readers to take various beneficial actions, and to adopt associated beneficial attitudes (e.g. avoiding counterproductive guilt), without being too concerned about whether the beneficial actions and attitudes are objectively fitting. And that makes sense — it’s a fitting choice of focus — because saving lives is much more important than having fitting attitudes.

(I do fully agree with Johann, though, that instrumental expressions of praise and blame are an entirely different matter from adjudicating when these attitudes are truly fitting.)

A de-emphasis on the deontic also ties in with Tom’s interesting observations about methodology. I think a promising way for Singerians to thread the needle here is not to claim that intuitions about principles are more reliable than intuitions about cases, but to instead argue (as I do in my book) that *telic* intuitions are more reliable than *deontic* ones. When we judge that it’s *really important* to stop kids from starving or drowning, or to prevent torture to animals, these are excellent intuitions that we should not want to downgrade in the slightest. Are we *obliged* to help them? *shrug*, who cares? Nobody seeing a kid drowning in a pond should respond by asking, “But do I have to?” It’s clearly what we have *most reason* to do, whether or not it strictly qualifies as a “duty”. Ask less about duty, and more about what’s worthwhile, is the general gist of my project.

P.S. In case anyone’s interested, I previously shared some reflections on Singer’s career and retirement conference, on my blog: https://www.goodthoughts.blog/p/reflections-on-peter-singer

re: Alec Walen’s suspicions that self-identified utilitarians are all “liars”: Wouldn’t it make more sense to be suspicious of those who *don’t* so self-identify? Those of us willing to take the PR hit clearly have a strong commitment to honesty! Any truly Machiavellian consequentialists will presumably be masquerading as deontologists.

More seriously, as Adriano attributes to David Enoch, often the stakes are sufficiently high that moderate deontology makes no practical difference. If anyone is to justifiably abide by commonsense moral constraints, it will have to be because such norms are instrumentally warranted. Cf. ‘Stakes can be high’: https://www.goodthoughts.blog/p/stakes-can-be-high

Hi Richard, good of you to chime in!

Without wanting to pronounce on the merits of the ‘scalar-ish’ consequentialist project that you’re pursuing, just two quick points of Singer-exegesis: